...where the gritty stuff happens.

Comments on New Mexico?

New Mexico is a paramnesic state, enchanted certainly, and often misplaced by cultural amnesia. New Mexico Magazine's famous, "One of our Fifty is Missing," (click picture at left) testifies to its El Dorado-ness, but traveling west across the Texas panhandle, or east across the Arizona border, reveals a sagebrush Brigadoon calling itself, "The Land of Enchantment."

The magazine dates its running tretise on geographical dementia to the early seventies, but many remember spotting "One of Our Forty-Eight is Missing" in the fifities. The usual parade of geographic delinquents include postal officials demanding customs forms, and mail order companies refusing service to "foreign countries," but the depths of New Mexico perplexity, like the famous caverns, have never been plumbed.

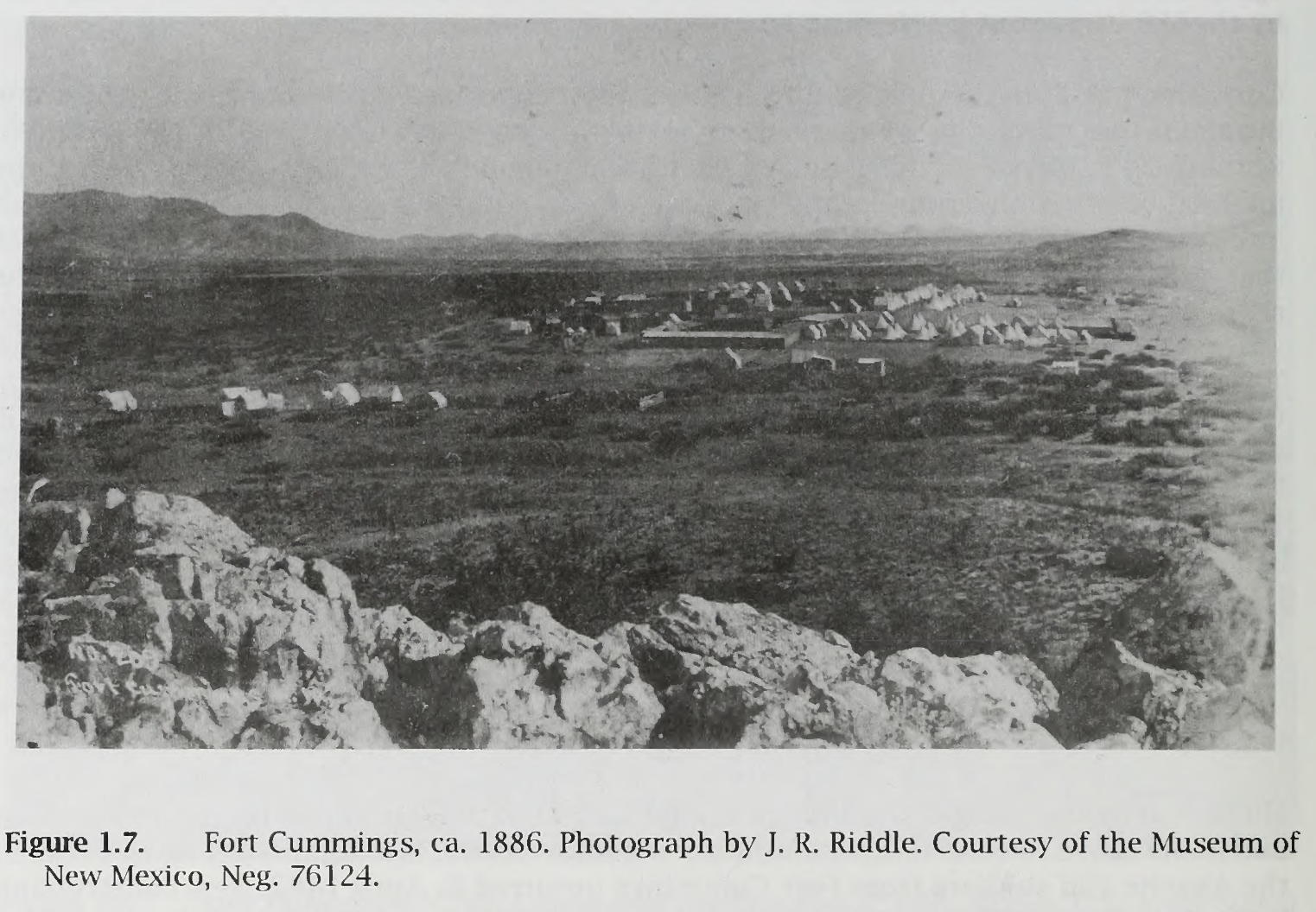

Several Southern New Mexico musings gather elsewhere in the Attic of Gallimaufry, including the first presidential visit, lawmen (and lawlessness), school lessons, a radio announcer from Carlsbad, a Vietnam-era chum, a fort, a football season, an aspirational village, and the town most often believed fictional.

On the rest of this page we have other salty meanders through southern New Mexico, where the scruffy stuff happens.

The New Mexico Territorial name originated in 1563 when Spanish explorer Francisco de Ibarra headed north looking for the golden city of Copala (Cibola), and announced he'd found a Nuevo Mexico. Juan de Onate, first colonial governor of New Mexico, and comprehensively unpleasant fellow, made the name official in 1598, before fleeing back south.

President Polk's Manifest Destiny war with Mexico brought New Mexico to the United States. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) set the major boundaries, and the Gadsden Purchase (1853) acquired the Gila River area for a southern railroad route.

The current boundaries formed gradually. First, Texas' claim to a swath east of the Rio Grande died when Texas became the 28th state in 1845. Later, New Mexico's claim, based on a surveyor's error, to some of Texas' Permian Basin petered out. When the Tucson area seceded in 1862, and joined the Confederacy, Lincoln split New Mexico Territory roughly in half, calling the western side, including the rebellious part, the U. S. Territory of Arizona. Texas tried to claw back its New Mexico Territory during the Civil War, but in 1862 the battle of Glorieta Pass soured them on the notion.

After the war the new boundaries stuck, although Texas still sometimes makes annoying gestures toward Albuquerque.

The Territory of New Mexico lobbied for statehood for decades, but there was little interest. It seemed like a pretty rustic, and violent place (it was), and there was always an opposition of indifference. In the early part of the twentieth century Teddy Roosevelt was against it, but his successor, Taft, broke with him and New Mexico became the 47th state, January 6, 1912, a month and 8 days before Arizona.

The late Pete Hendrickson (1936-2017), NMSU history professor, and all around good fellow, discussed the agonies of New Mexico statehood at the Alamogordo Public Library in 1977. You can listen in nearby.

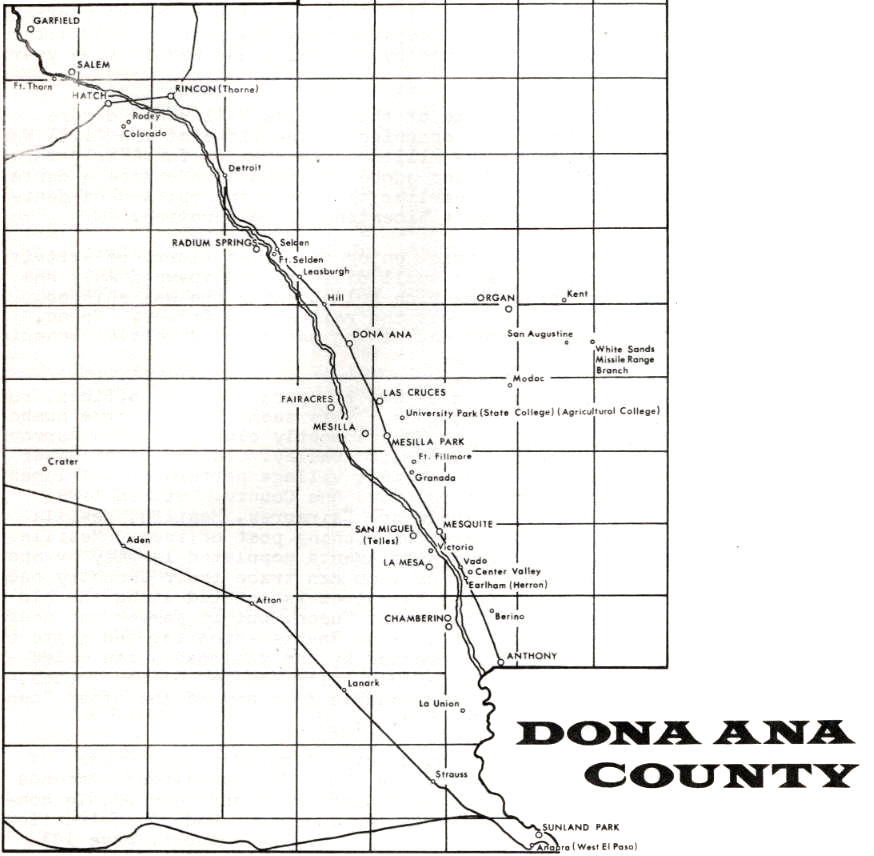

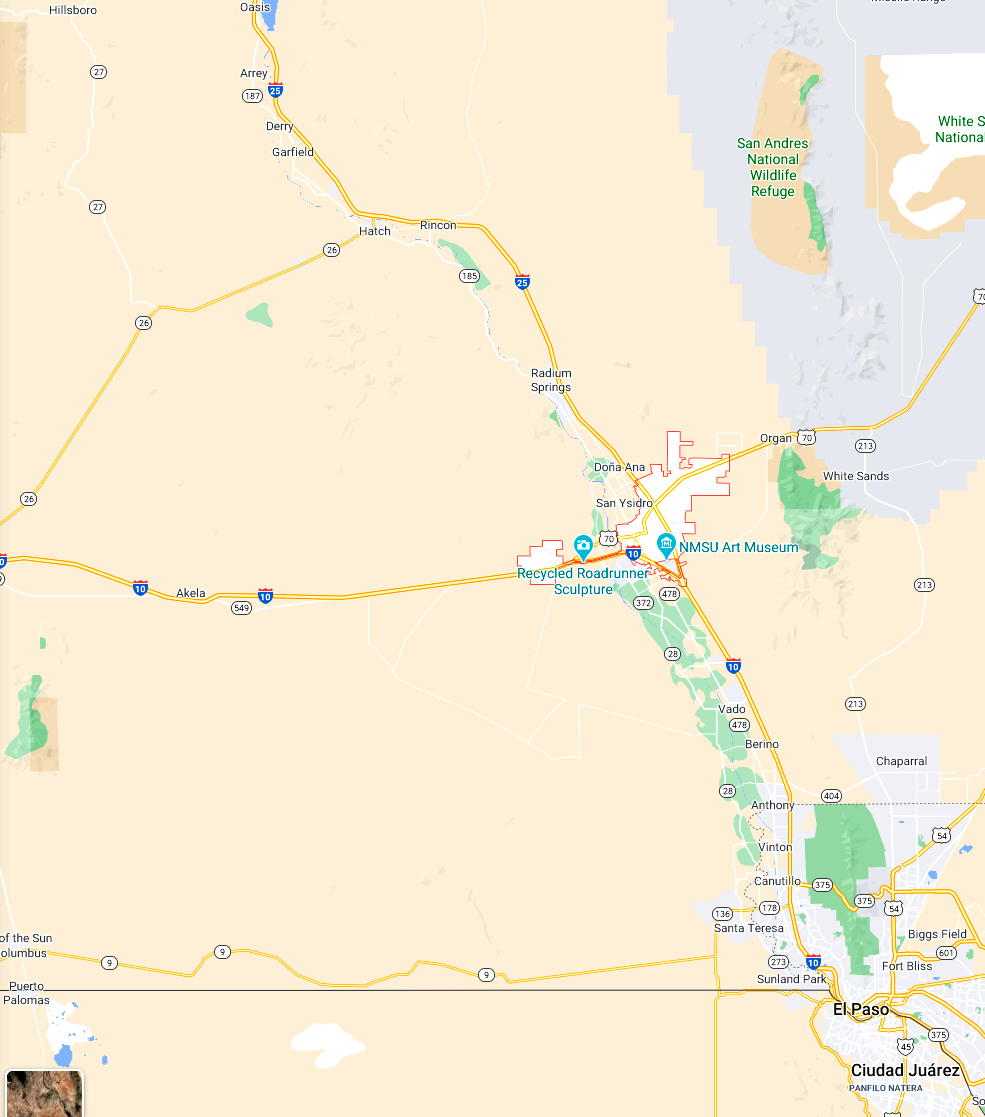

Although the territorial government never issued automobile license plates, some local authorities required them as early as 1910, two years before statehood. Bill Johnston and Richard Miller, of Organ, New Mexico (see left), share their extensive research into New Mexico license plates on their web site (linked from the picture). You might want to start with a look at the "Quick links" tab.

Eric Taylor shares his extensive research on porcelain license plates at his web site. The picture of a 1920 motorcycle plate (right) links to the New Mexico section of his web site. You'll probably want to check out his other research as well.

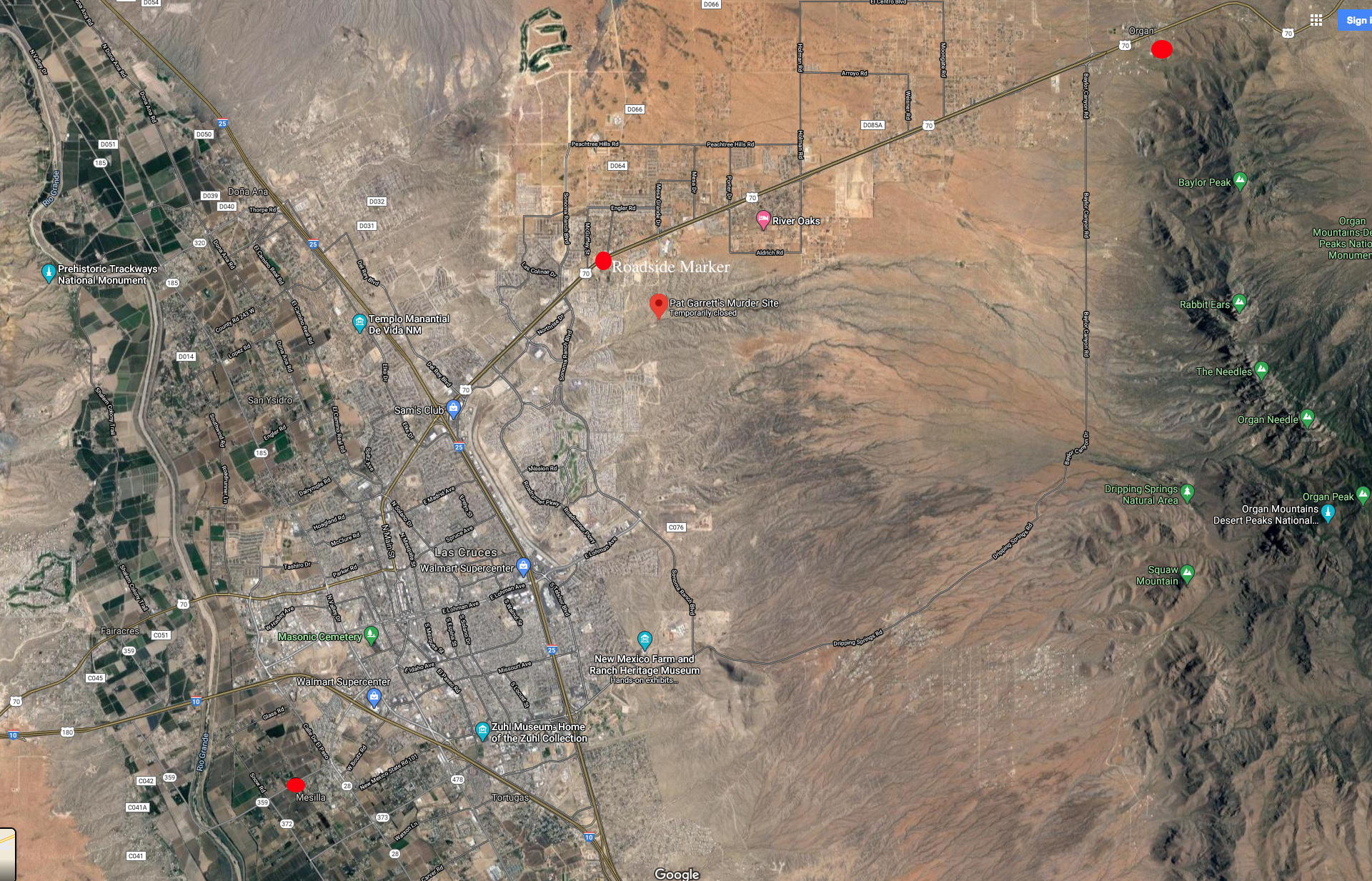

By the way, if you're wondering about Organ, New Mexico, no, it's not a local misspelling of Oregon. It has nothing to do with a desert-longing for the Northwest Territory, nor oregano, nor El Orejon, nor ouragan, nor an engraver's error, nor any other disputed origin of our 33rd state's name. It's a tiny town in the San Augustin Pass separating the Organ Mountains from the San Andres Mountains to the north.

In 1964 I refilled my radiator at this Organ station before breaking down on my way up to Cloudcroft. It links to a modern-day take on Organ (I never ate at the sandwitch shop).

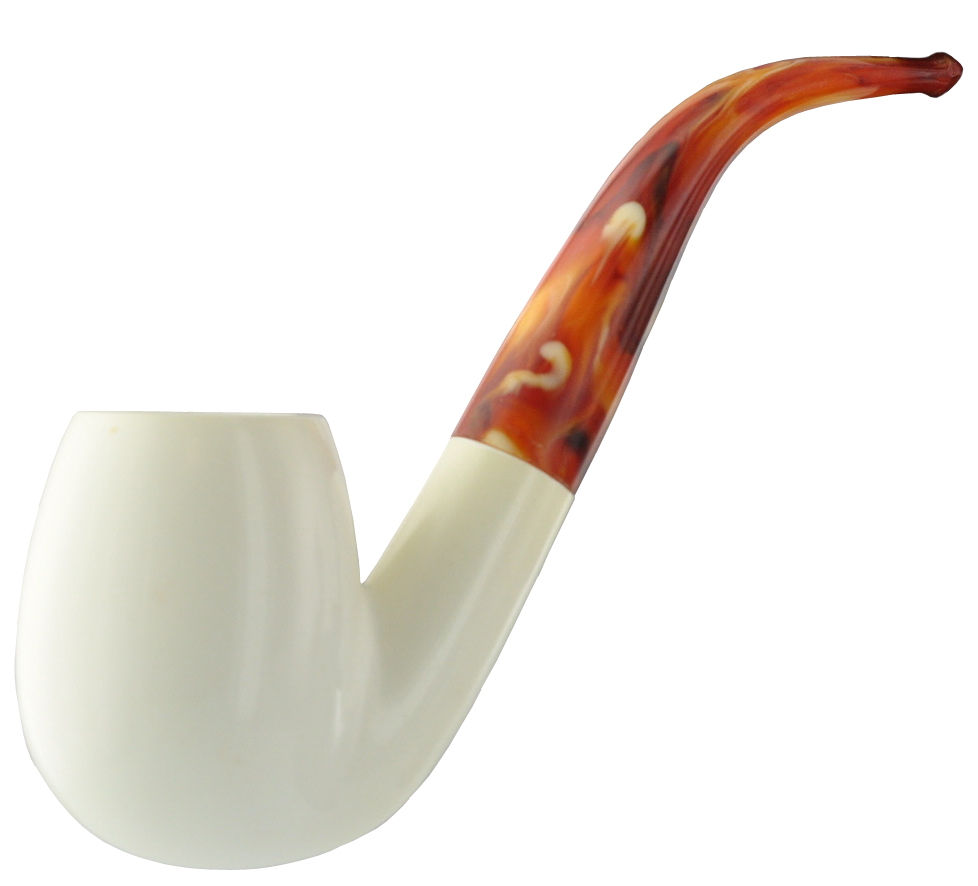

The Organ Mountains lie on the east side of the Rio Grande Rift Valley, just north of the Franklin Mountains, and are named for their pipe-like flutes that rise above Las Cruces, suggesting an organ. Our old friend Don Juan Onate noted them in his journal when he blazed Spain's Camino Real del Adentro from Mexico City to Santa Fe.

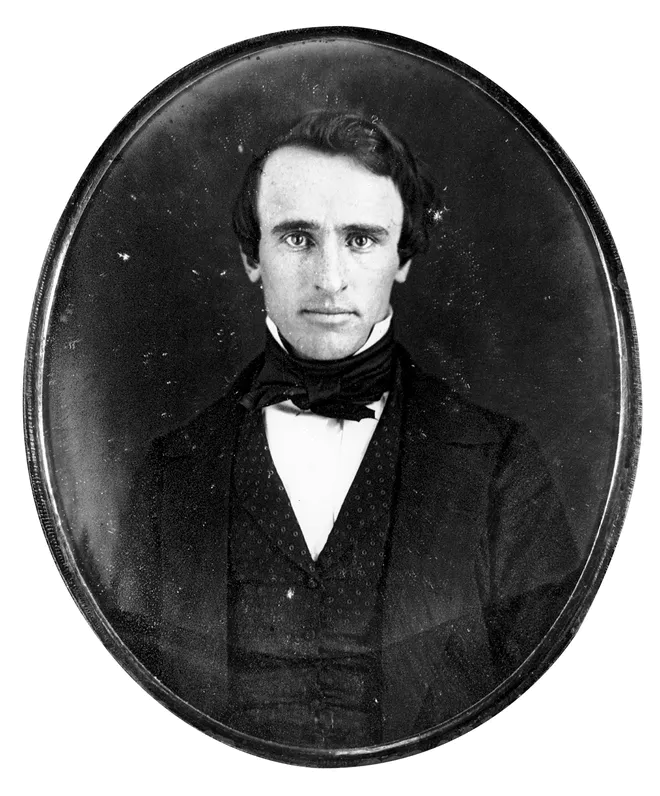

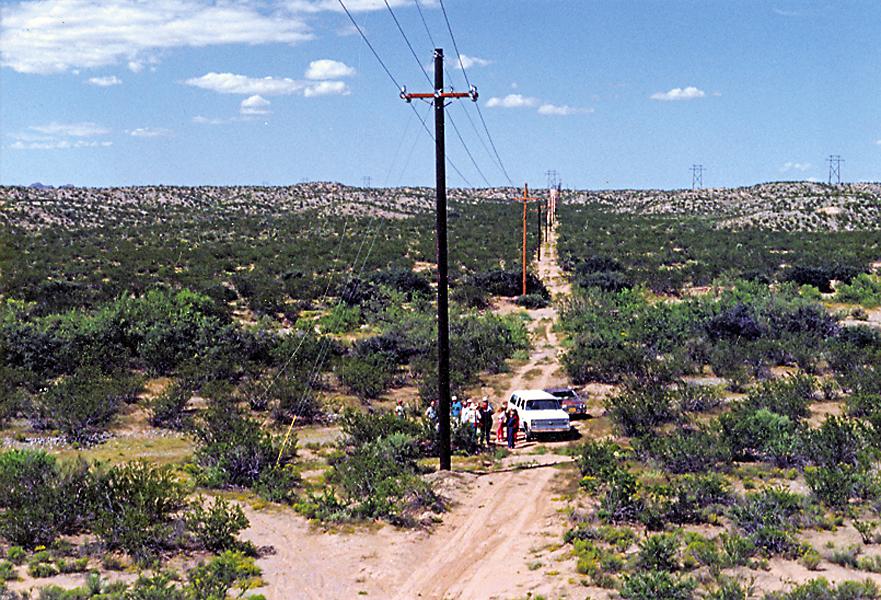

Roadside sign near Pat Garrett murder site. Click for popup about Garrett's death.

The range slightly northwest of the Organs is where one of Onates' band, Pedro Robledo, managed to drown, and it bears his name, but the Organ's seem to have been named by some unknown Europeans in 1682.

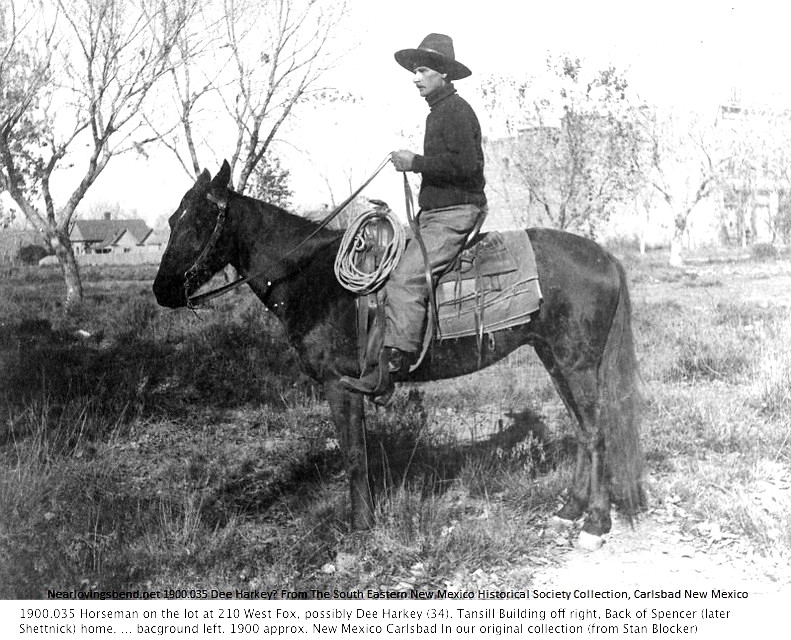

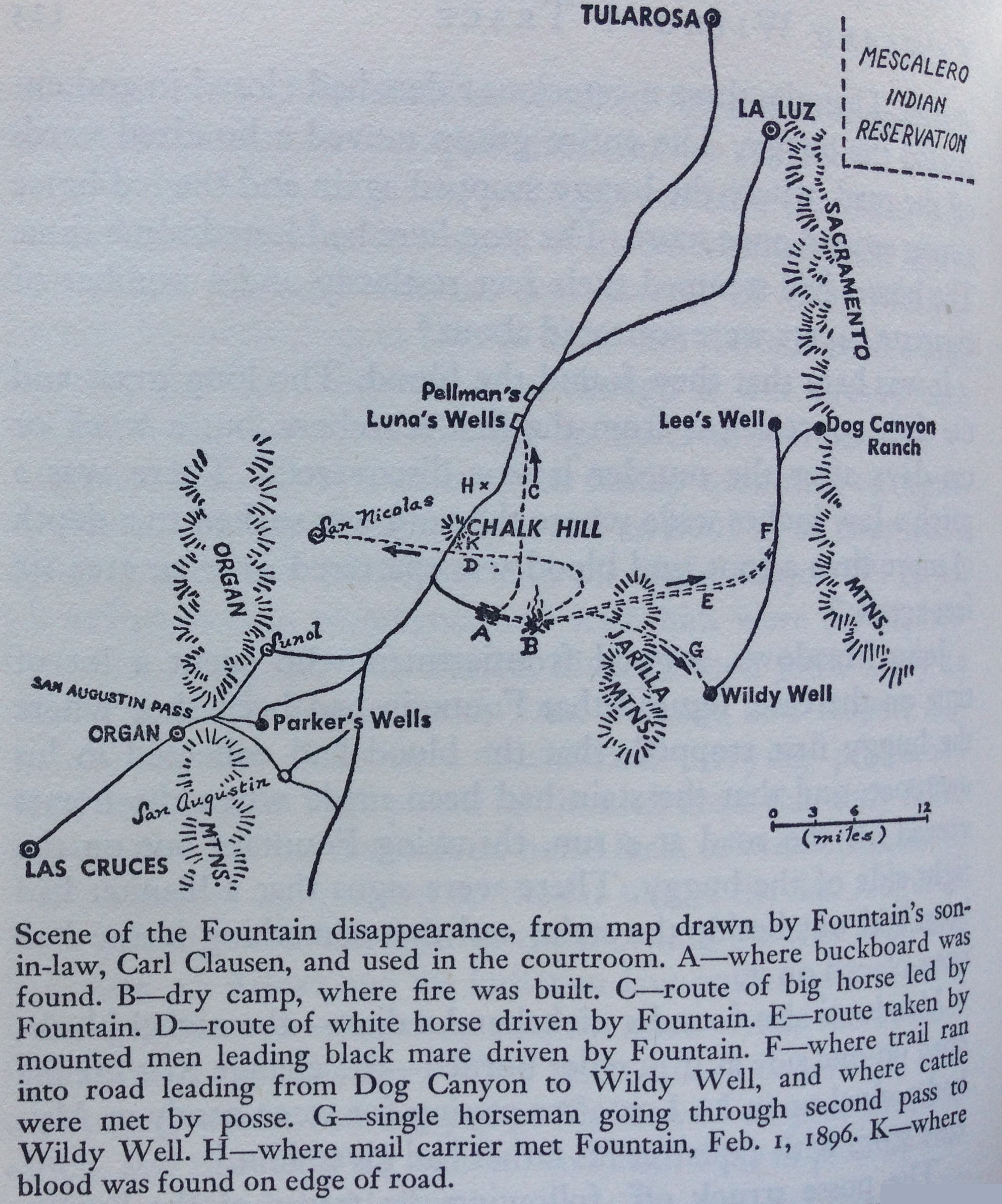

Organ, besides being home to the state's foremost license plate archive, gets a footnote as the place Pat Garrett was riding away from when he was shot in the back near Alamedo Arroyo. There's allegedly a plaque at the site, but it's hard to find. Click the link at right to get some immediate information or the one above about Fountain and the Tularosa Basin to learn more about Garrett's last moments.

To see some southern New Mexico scenery, without traveling, follow along with an RV enthusiast. The first part of his trip is in Texas, so the link (left) skips most of that boring stuff. Scroll down a bit and you'll be in Lincoln, New Mexico.

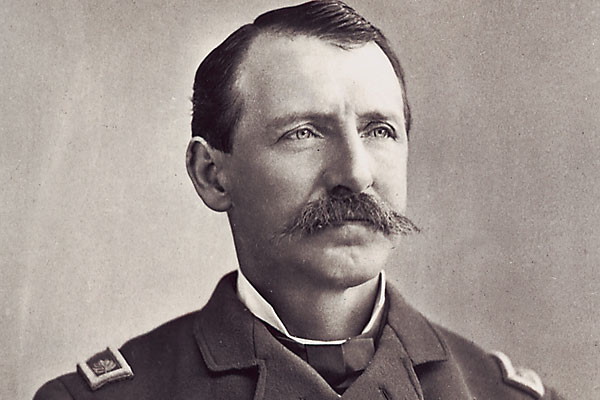

Our guide visits the courthouse, the Tunstall store, and other Lincoln County War relics. From there he goes to Fort Stanton, finds an early picture of Black Jack Pershing of Pancho Villa/WW I fame, and discovers Fort Stanton was a German Detainee camp during WW II.

He heads off to White Sands Missile Range, where he sniffs evidence of the atomic bomb and early missile programs, then to Fort Selden (see above link) in the Mesilla Valley, where General Douglas McArthur learned to ride and shoot, on to Percha Dam State Park, Gila National Forest, and back to Trinity Site: the grand tour of things west of the Pecos Valley.

SILENTIUM

SILENTIUM

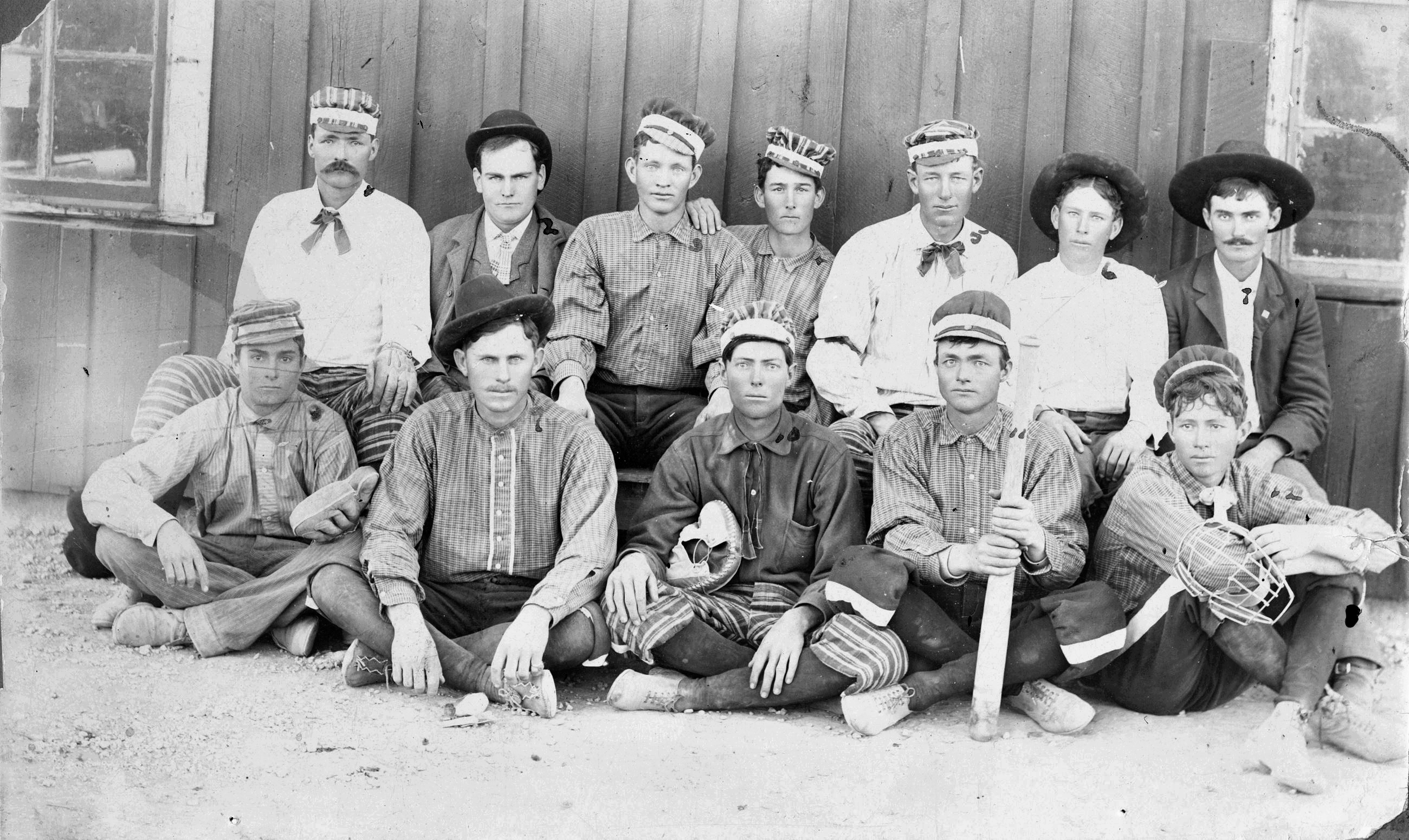

A preference for human drama over popular sensation can render trivia questions untrivial. Consider this. When Barry Bonds hit homerun number 73 in 2001, whose professional baseball record fell? Right, it wasn't Mark McGuire's unless you read "major league" baseball instead of "professional." The answer is Joe Bauman's mark of 72 homeruns in 1954, when he was playing for the Roswell Rockets. Joe Bauman gets us right inside the multi-threaded human drama.

Joe Bauman hitting a homerun in 1954. The image links to some NY Times journalism. Remember this story if you ever visit the ballpark in Roswell, especially if you're 83.

In those days Roswellians weren't fully woke to their recent invasion by Martians. They were still going about things unaware they'd been elevated to Harvey-House status on the intergalactic highway. The cold war and baseball were their diversions. The Rockets played in the Longhorn league that year.

The Rockets red glare was challenged by the Carlsbad Potashers in 1954, and the fertilizer boys were too much for them. The Rockets were second in the Longhorn rodeo, but along the way Joe Bauman grabbed some extra cash by launching 72 homeruns.

Much of what we read about Bauman originates with a former teammate, Jim Waldrip. New Mexico Magazine tagged after him a few years ago and ran the article by Toby Smith linked at right.

Joe was one of those rarities in American celebrity, a man who valued what we redundantly call his "personal life" above the promise of celebrity. There are numerous sources to get the known facts, but if you want a brilliantly written, feel-of-the-season, 1954-centric narrative of Bauman's chase for the record, try Joe Posnanski's article, published on his website at the link below, or the one on Gary Cieradkowski's blog next to it.

Bauman's human drama became personal for me when I discovered a long lost branch of my mother's family, including a relative named Pat Stasey. He managed the Roswell Rockets during Joe's record-setting year. He moved Joe up from cleanup spot to leadoff, giving him more at bats for the year. Stasey's professional baseball career spanned the years 1938 to 1955. He was a fearsome hitter whose best days were at Big Spring, Texas.

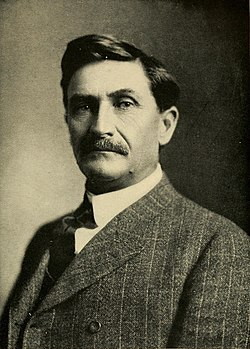

He was in and out of Carlsbad playing the local Potashers in the early 1950s, and we moved there in 1955, but we knew nothing about that branch of the family, and Pat may never have visited while we were there anyway. After retiring his bat, he went to the Midland Indians as GM. Pat's picture, below, links to a story about his legacy in the Stasey family. He also appears in the entertaining, "Left on Base in the Bush Leagues," by Gaylon H. White.

He is featured in the book, "Stealing Home," written by his daughter, Patricia Stasey Aylor, another long-lost relative. She wrote about her father's love of the land and his love of baseball. The Stasey family hold an annual family reunion at Stasey Field, near, Chalk Mountain, Texas. She invited Gaylon H White, author of "Left on Base in the Bush Leagues," to the reunion one year to fill him in on her fathers' life.

SILENTIUM

SILENTIUM

This is the photo Charley Montgomery used to measure Gil Carter's homerun in Carlsbad, NM. It links to an article in Elysian Fields Quarterly.

I've been reminded of another New Mexico baseball phenomenon, this one at Montgomery Field in Carlsbad. On August 11, 1959 Carlbad Potashers outfielder Gil Carter hit a 730 foot homerun off Odessa Dodgers pitcher Wayne Schaper. Carter hit a first-pitch fastball into a peach tree two blocks away.

The homeowner found the ball under her tree among some peaches dislodged by the mighty thwack. Club owner, Charley Montgomery (see name of field, above), used the local sports editor's aerial photograph, and some plat maps (Charley developed the neighborhood near the field) and calculated the distance. The "Carlsbad Current-Argus" documented Mr. Carter's feat, as did "The Sporting News," and "Sports Illustrated" (twenty-one years later). Fearing ridicule, these and other stories arbitrarily reduced the measured distance to 650 feet.

The Minor League Baseball Encyclopedia uses the shorter, baseless, distance for its official citation. At right, is the aerial photo used to measure the length of the drive. It links to the Elysian Fields Quarterly article of 2001 by Jerry Dorbin.

Archie McCoy remembers it this way: "I was the batboy for the Potashers the night Carter hit that homerun. It cleared the alley, the house, and the street , landing in the yard across the street. I don't recall if it was backyard or not. I doubt the physics of hitting a baseball 700 feet is possible without a good roll or bouncing off concrete. The history of baseball on the major league level is high 500's. Gil Carter was a big strong man that could hit the ball a long way."

Carter later remarked, "I haven't hit a ball harder and certainly not that far. I watched it go, and it came down two blocks from the ballpark. I knew it was something special. I could feel it in my bat when I hit it. I just stood there and watched it."

Carter played in the Negro Leagues for the Kansas City Giants and the Memphis Mud Hens before signing with Chicago Cubs scout, and legendary Negro Leagues player, Buck O'Neil. Gil played three years in the Cub's minor league system.

Gil Carter died in 2015 in Topeka Kansas. He has been inducted into the Shawnee County Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame, and received the Pride of Kansas Award from the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame.

His short professional career ended with the Northern League All-Star team in 1960. He later drove a bus in Wichita, played semi-pro baseball, fast pitch softball, and did extensive work with youth programs in Wichita and Topeka. He helped the Wichita Rapid Transit Dreamliners win championships in 1962 and 1963.

The picture at left links to an article in the July 25, 2015 Wichita Eagle, about Carter's award from the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame.

Below are links to more things Gil Carter, along with a video that features an interview with him late in life.

SILENTIUM

SILENTIUM

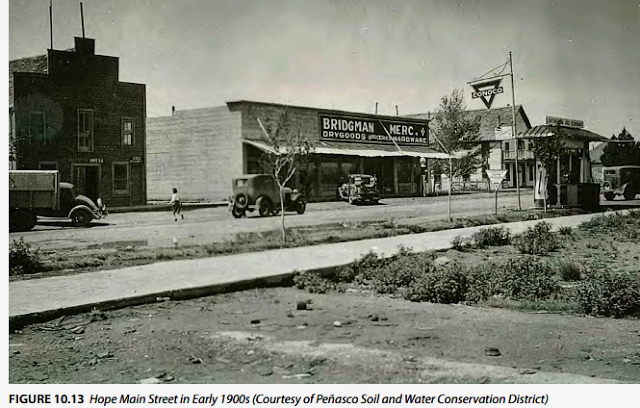

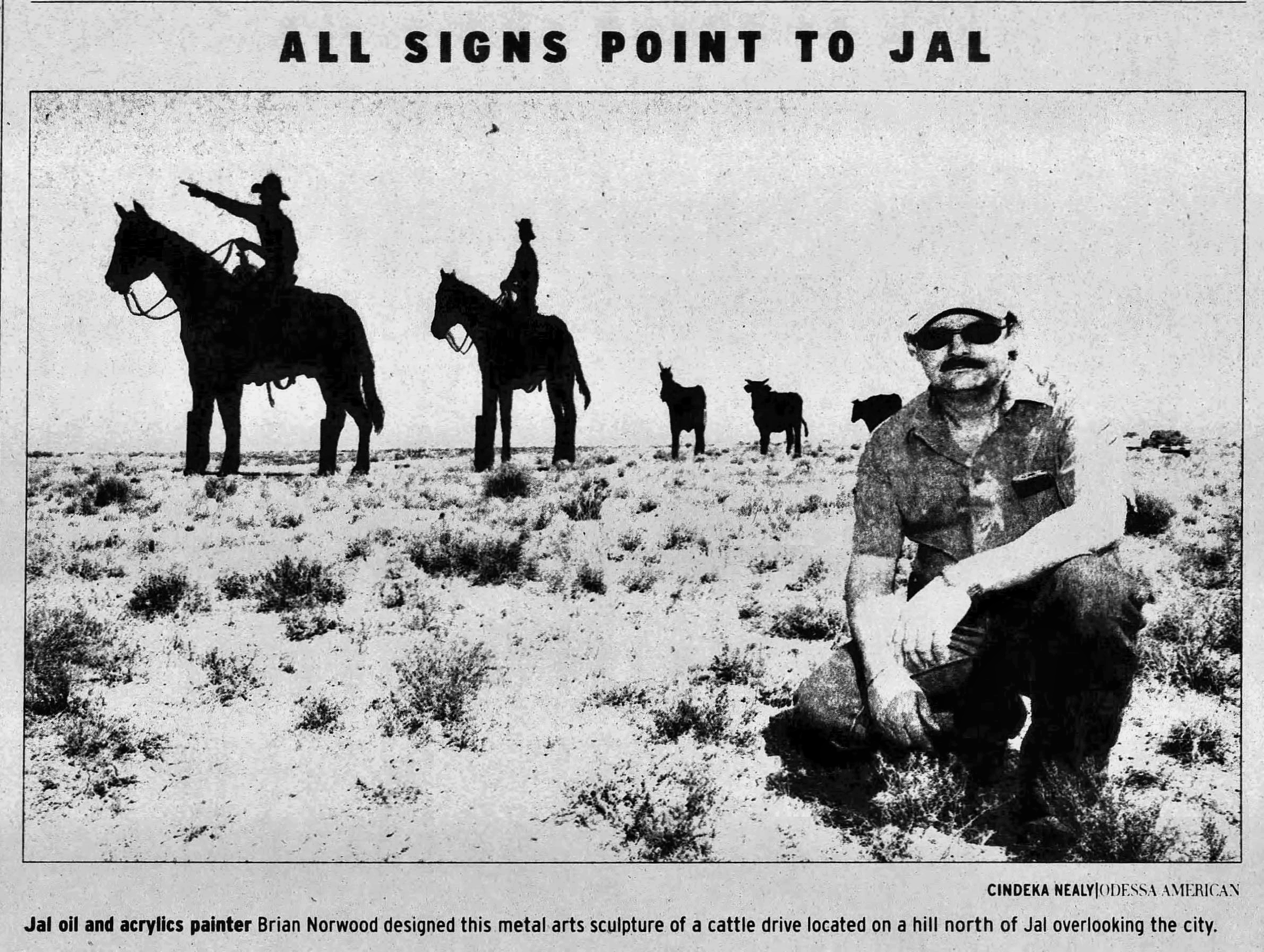

Our neighbors up around Santa Fe and Taos sometimes forget there is any enchantment south of Albuquerque. That’s understandable given the rich culture and extravagant beauty of that area. No one could blame them for being provincially enchanted. Driving into the desert, though, will get you to things like this. These cowboys and critters grace the skyline outside Jal in a perpetual range-ride worth seeing. They're the work of artist Brian Norwood, and there is a story (click picture) about his work, "The Trail Ahead." It serves as primer to the little town of Jal, and endnote to the old west. You should note that the Wikipedia entry for Jal misplaces its history by about a century. The Cowden brothers arrived in the late (not the "early") 1800s.

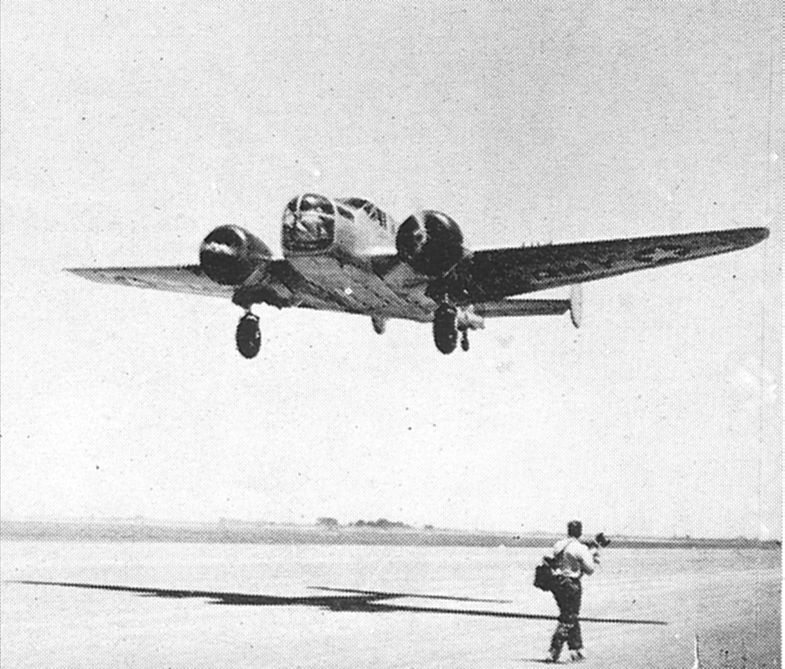

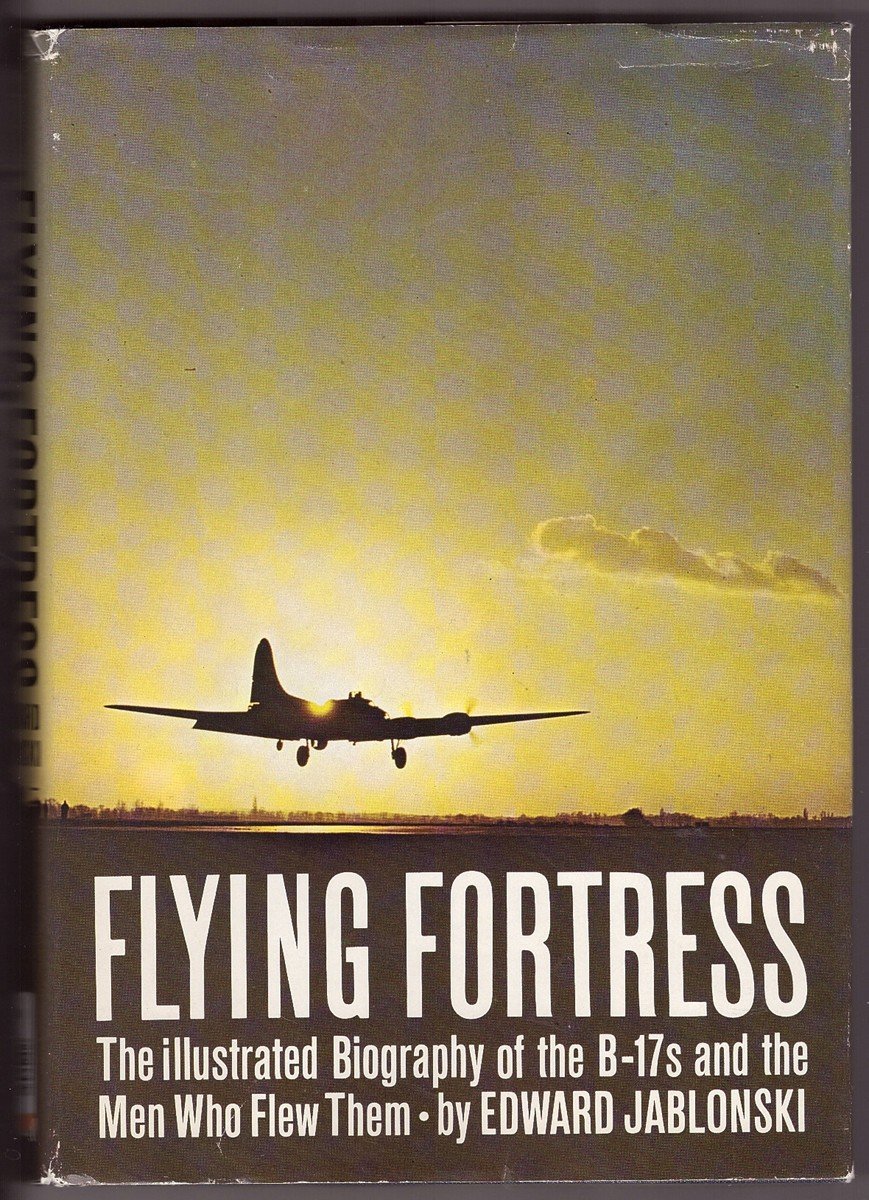

Or you could pause further north (see below), and catch a glimpse of Norwood's "Fortress on the Plains," a WW II B-17 and crew at the old Hobbs Army Airfield (linked to Norwood's web site).

Below the B-17 you see the tunnel between Cloudcroft and Alamogordo. It links to some bikers riding down from High Rolls.

Finally, we get to the obligatory video of Carlsbad Caverns, where I was fired from my first job, back in the days when I wasn't quite sure about that "permanent record" business.

The Internet is profuse with Carlsbad Caverns stuff, including travelogs and arcana. Below you'll find a couple of stories less traveled.

If you decide to go to Mudgap, just north-west of Las Cruces, you won't find it on search engines. The Army has secrets in that part of New Mexico, but will claim to know nothing. No end of enchantment.

Who in the world cares about New Mexico?