E. J. Couzens is a hard man to pin down.

Our man is probably not Edrick James Couzens, who was part of the Worcestershire Regiment, and was killed 8 July, 1916.

In 1906 an E. J. Couzens ran a retail outlet for furs in Cheltemham.

In 1919 an E. J. (Edward) Couzens presided as Grand Primo at a meeting of the R. A. O. B. (Royla Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes) at a welcome home dinner for "brethren who had served overseas during the war. It is unclear if Couzens was among the returnees. In 1963 this E. J. Couzens was a member of the Malmesbury Borough Council, overseeing building permits. He died 8 Nov 1969, age 88. His obituary says he was in the building contractor business, and an alderman of Wilshire County council and a member of the Malmesbury Rural Council. It doesn't mention any war service, or anything to do with engraving.

A private Couzens seems to have been part of the 1/1st South Midland Mobile Veterinary Section some time between 1915 and 1917. He went on leave in November, 1915.

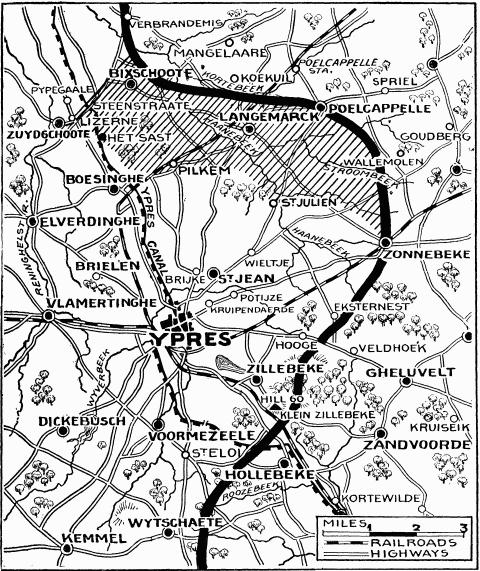

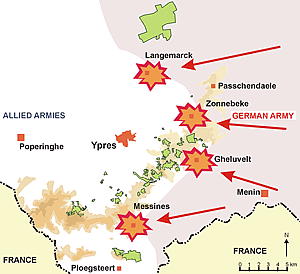

A corporal Couzens, of the Essex, machine gunner, did heroic service in the first battle of Ypres. Sergeant Couzens scored highly in a civilian shooting match in 1923, Leicester. This was probably Walter George Couzens, 1896-1979.

Couzens, 7905, Sapper H. A. Royal Engineers, was wounded 16 Nov 1914.

There was a John Cousen, born 1887, married to Rose King in 1912, probably related to John Harold Cousen who was a sapper in WWII. They had a son late in life named Ronald: Ronald served with the 221 Field Company, Royal Engineers. The 221 Field Company landed in Salerno in September 1943 and fought in the Italian Campaign against the Germans alongside the American 5th Army as they advanced Northwards. Ronald died during bitter fighting for the town of Minturno which lay at the end of the Gustav Line - a German line of defence stretching from West to East across Italy.

A John Cousins, born 1887 from Southwick-on-Wear Sunderland, Yorkshire Northern, service number 322404, was a sapper in the Royal Engineers in WW I, pensioned out 12 Oct 1918 with an un-described disability. A sapper is a soldier who performs engineering duties. He seems to be the son of the above John and Rose, according to the 1911 census. He appears on the roster in 1939, full name John Frederick Cousins, living with John and Rose, and working as a Hotel Door Porter. A John F. Cousins died in 1962. These may not all be the same person. The one who died seems to have been born in 1892-4, while the sapper seems to have been 5 or 6 years older.

In 1953 an E. J. Cousins, 63 Somerton R. Newport, England, born 1887, Ironworker, went to Sydney, Australia in 1953, and returned in 1956. He seems to have immigrated in 1913 from Australia, and made several trips back and forth over the years.

An Ernest Couzens was born in Essendine, the youngest son of John and Mary Couzens who later moved a short distance away to Carlby in Lincolnshire. He joined the 7th Battalion Leicestershire Regiment and went to France on 29 July 1915. He was killed during the Battle of the Somme on 14 July 1916 in an attack on Bazentin Le Peitit Wood (before the Sherwood Foresters, not part of the Leicestershire Regiment) reached Ypres. Ernest is buried in Flatiron Copse Cemetery near Mametz, grave II.C.6.

There was an Edgar Couzens in the Northumberland Fusiliers Army Veterinary Corps, who later ran a butcher shop in New Castle.

Ernest James (E. J.) Cousins was a Canadian, 1883-1957, who went to war with the Canadian Forestry Corps in 1917, and was invalided out in 1918. He was married to Alice, and they are both buried in Canada, her in 1950, and him in 1957. He was a teamster before the war, and maybe ran retail businesses afterward. It's unlikely he's our E. J. Couzens, but it's possible. The CFC may have been around Ypres, and Cousins may have transferred to the Canadian Engineer Corps, which built roads and railways in the area. Probably far fetched.

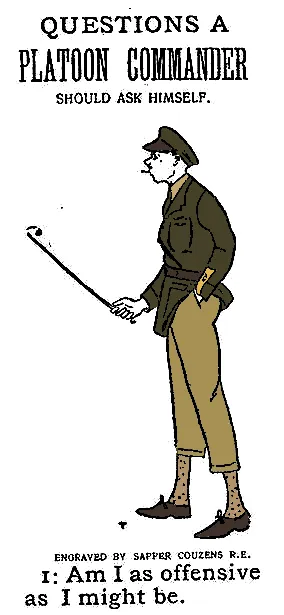

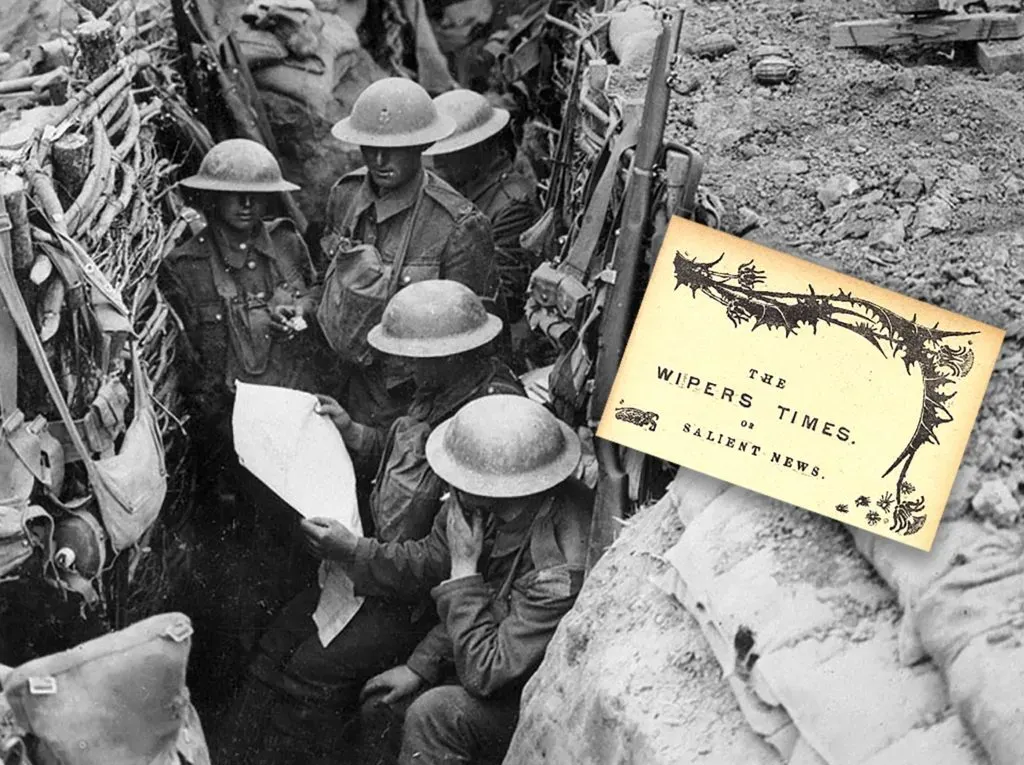

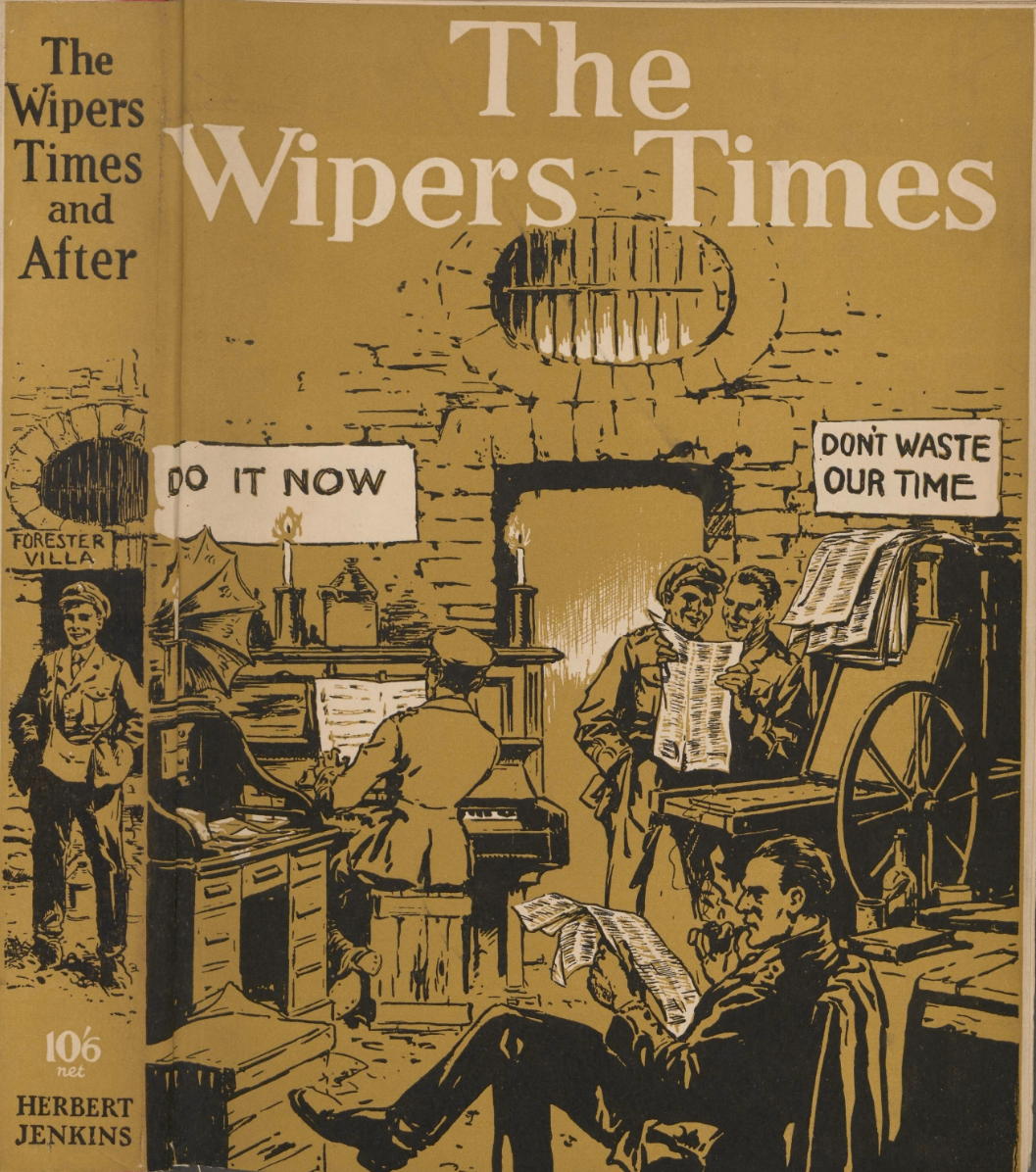

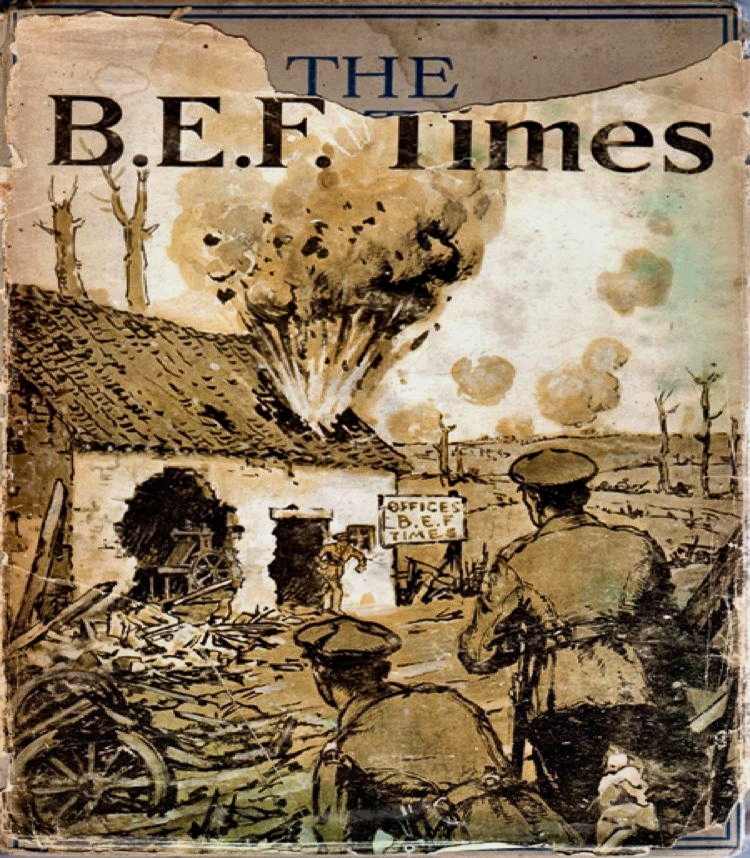

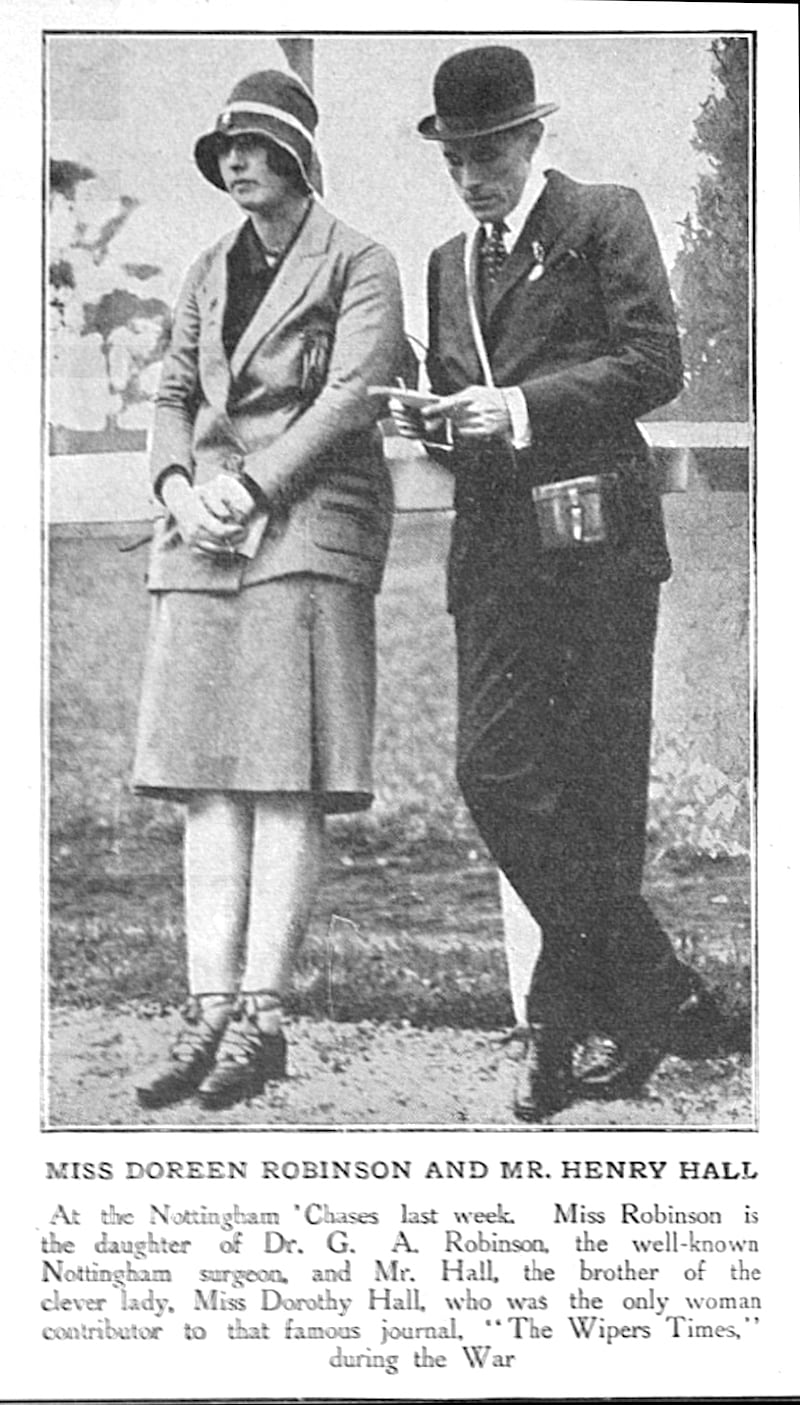

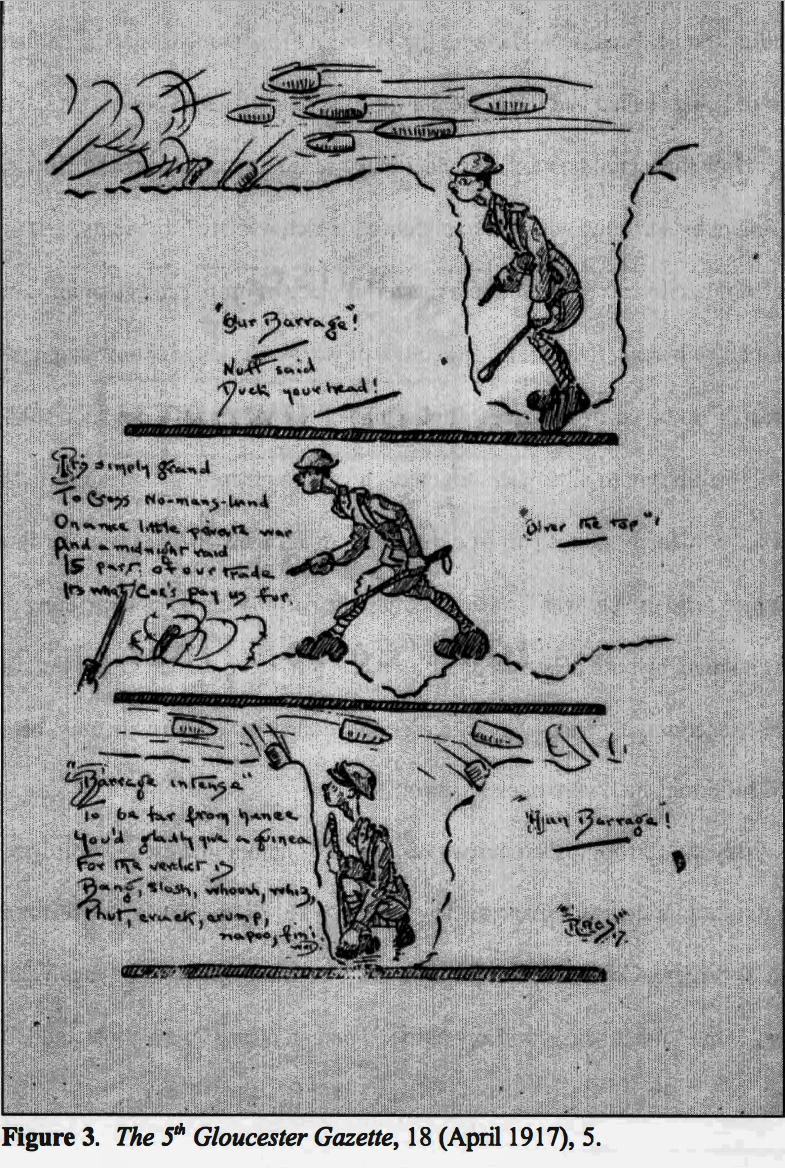

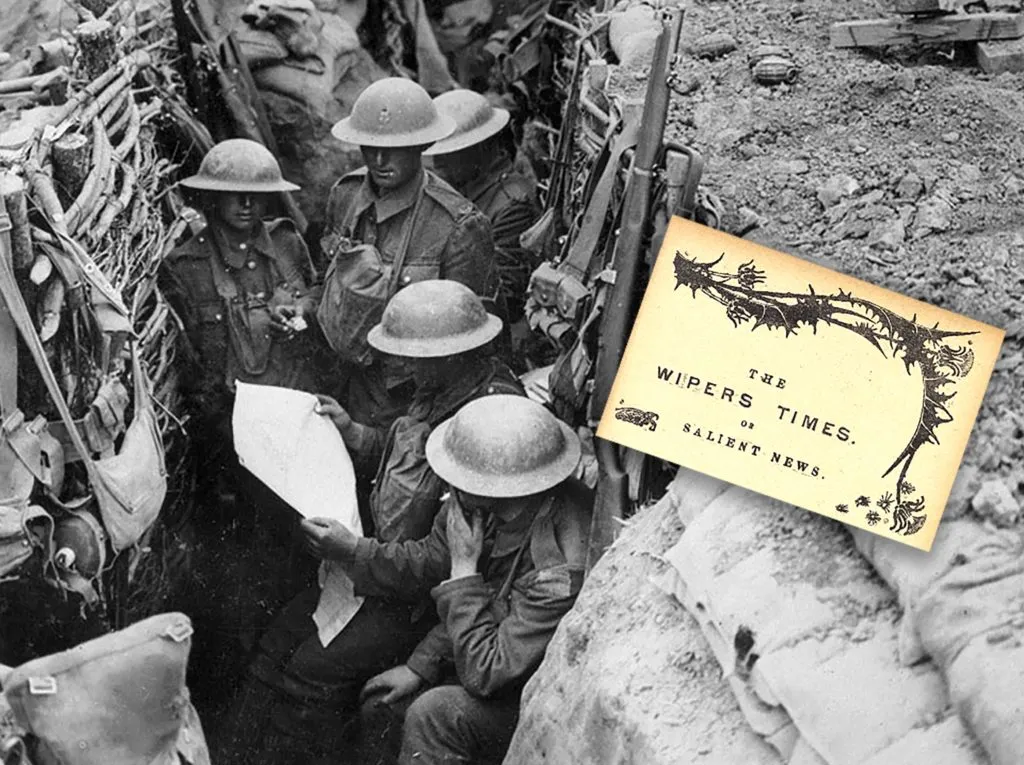

Our most promising lead is a wartime record of E. J. Couzens, sapper in the Royal Engineers, who was nominated for decoration in 1919. This may be our man. Also we've got an E. J. Couzens appearing in a 1939 London directory with an occupation of "Wood Engraver." We don't know if they're the same people, and more instances of the wood engraver are not found, but it's easy to imagine he's our World War I illustrator of the Wipers Times, but….imagination is not proof.

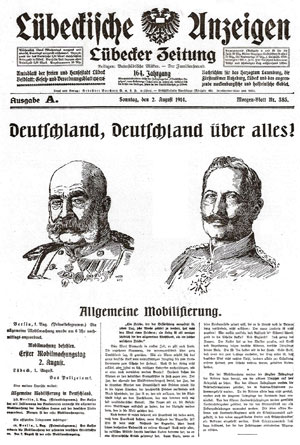

By the way, should we think there is some similarity between the Couzens Coat of Arms, see nearby, and the banner symbol at the top of each Wipers Times issue? Hmmm.