Time

(Duration)

|

WJSV's September 21, 1939 Schedule

|

Program Source and

Program Type

|

Primary Sponsoring Product

|

Additional Information

|

6:00 AM

(30 min.)

|

Sign-on / Sundial

|

Local programming:

Recorded music

|

Sustaining

(i.e. unsponsored)

|

A period of dead air occurred between approximately 6:14 and 6:23 a.m. when the station left the air "to make technical adjustments."

|

6:30 AM

(120 min.)

|

Sundial continues, joined by host Arthur Godfrey.

A 5-minute Arrow News Reporter aired at 8:00 a.m.

|

Local programming:

Live talk, news, and recorded music

|

Various national and local advertisers

|

Joe King of WJSV was the 8:00 a.m. reporter.

Network note: This local programming pre-empted the CBS network's Richard Maxwell (8:00 a.m.) music program and Meet the Dixons (8:15 a.m.) serial drama.

|

8:30 AM

(15 min.)

|

Certified Magic Carpet

|

Local programming:

Audience quiz

(transcribed)

|

Certified Bread

|

Note: Host John Charles Daly calls himself simply "Charles Daly" when doing this local program. It was recorded a block away at the Willard Hotel with members of the local Soroptimist Club.

Network note: This pre-empted CBS's Manhattan Mother serial drama.

|

8:45 AM

(15 min.)

|

Bachelor's Children

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Old Dutch cleanser

|

Today's story: A discussion of plans to bring a bill before the legislature for a proposed sanitarium.

|

9:00 AM

(15 min.)

|

Pretty Kitty Kelly

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Wonder Bread

|

Today's story: Kitty is in jail for murder and foreign spies are suspected. A search continues for the gun.

|

9:15 AM

(15 min.)

|

Myrt and Marge

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Super Suds granulated soap

|

Narrator: "The world of the theater, and the world of life, and the story of two women who seek fame in the one and contentment in the other."

Today's story: Work on a new show begins, but there are concerns.

|

9:30 AM

(15 min.)

|

Hilltop House

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Palmolive soap

|

Narrator: "The story of a woman who must choose between love and the career of raising other women's children."

Today's story: John's detested sister-in-law has a request.

|

9:45 AM

(15 min.)

|

Stepmother

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Colgate tooth powder

|

Narrator: "Can a stepmother successfully raise another woman's children?"

Today's story: Mrs. Clark plots a dastardly scheme.

|

10:00 AM

(15 min.)

|

CBS News report / Mary Lee Taylor

|

CBS network:

CBS news / Cooking recipes

|

Pet Evaporated Milk<

|

Robert Trout reported the war news. Because a sponsor, and not the network, in effect "owned" a giventime period, CBS thanked the Pet Milk company for relinquishing part of its time.

Today's recipe: Stuffed vanilla wafers.

|

10:15 AM

(15 min.)

|

Brenda Curtis

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Campbell's chicken noodle soup

|

Today's story: Brenda has a chance to return to the stage. But her husband objects, even as he worries over a court case.

|

10:30 AM

(15 min.)

|

Big Sister

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Rinso soap powder

|

Today's story: A marriage approaches, and concern arises over a child's mystery illness.

|

10:45 AM

(15 min.)

|

Aunt Jenny's Real Life Stories

|

CBS network:

Week-long dramatic stories

|

Spry vegetable shortening

|

This week's story: A woman is conflicted between two men. Tomorrow, the solution is revealed.

Narrator: "True names are never used in Spry's Real Life Stories."

|

11:00 AM

(15 min.)

|

Jean Abbey

|

Local programming:

Woman's Home Companion radio shopper

|

Items at S. Kann Sons (Kann's) department store

|

Note: "Jean Abbey" was a pseudonym for Meredith Howard, who often used it for broadcasting and publishing purposes.

Network note: This local program pre-empted CBS's serial drama Joyce Jordan, Girl Interne, which on Tuesdays and Thursdays ran unsponsored on the network. (Local program listings from that period show that some stations aired alternate shows on those two days, others did not.)

|

11:15 AM

(15 min.)

|

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

>Prudential Insurance Company of America

|

Narrator: "Dedicated to all those who are in love ... and to those who can remember."

Today's story: A new apartment, marriage news, and Andy is holding on to an incriminating letter.

|

11:30 AM

(15 min.)

|

The Romance of Helen Trent

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Angelus lipstick

|

Today's story: Helen's plans to open a dress shop compel her to take on an unwanted employee.

|

11:45 AM

(15 min.)

|

Our Gal, Sunday

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Anacin aspirin

|

Narrator: "The story that asks the question, 'Can this girl from a little mining town in the West find happiness as the wife of a wealthy and titled Englishman?' "

Today's story: Hospital plans, and a surprising transfer request.

|

12:00 PM

(15 min.)

|

The Goldbergs

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Today's story: The Goldbergs are being driven back to New York by a mysterious and unsettling driver.

Sponsor note: Procter & Gamble, a major radio advertiser, sponsored all four shows that made up the following one-hour programming block.

| |

12:15 PM

(15 min.)

|

Life Can Be Beautiful

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

IvoryFlakes soap flakes

|

Today's story: Good news comes after a difficult search for work.

|

12:30 PM

(15 min.)

|

Road of Life

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Chipso soap flakes

|

Narrator: "Dr. Brent, call surgery. Dr. Brent, call surgery. Dr. Brent, call surgery ..."

Today's story: The murder trial begins for an eleven-year-old boy.

|

12:45 PM

(15 min.)

|

This Day is Ours

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Crisco vegetable shortening

|

Today's story: Eleanor worries that marrying her unemployed boyfriend could leave her as bitter as her friend.

|

1:00 PM

(15 min.)

|

Sunshine Reporter

|

Local programming:

News

|

Sunshine Krispy crackers

|

Hugh Conover of WJSV reports.

(The first couple of minutes of this program are absent.)

Network note: This local program pre-empted CBS's Doc Barclay's Daughters.

|

1:15 PM

(15 min.)

|

The Life and Love of Dr. Susan

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Lux toilet soap

|

Today's story: Dr. Susan Chandler helps out a baseball player, but makes an enemy of the mayor's wife.

|

1:30 PM

(15 min.)

|

Your Family and Mine

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

|

Sealtest, Inc.dairy products

|

Today's story: Judy stands by Woody, hoping an operation has restored his eyesight, even as Steve proclaims his love for her.

|

1:45 PM

(75 min.)

|

"Cash-and-Carry" speech

President Roosevelt's address to a special joint session of Congress, calling for an end to the United States' arms embargo on warring nations

|

CBS network:

News special

|

Unsponsored

|

Preceded by interviews by CBS's Albert Warner with Sen. Warren Austin, Rep. Bruce Barton, and Sen. James Byrnes.

Followed-up by the concluding portion of a live speech by shortwave by French Premier Daladier (in French), and then a brief English summary translation.

Network note: The CBS network's 15-minute music program Mellow Moments, planned for 1:45 p.m, was pre-empted. Also pre-empted was the weekly 2:00 p.m. 30-minute CBS network program of United States Army Band music. In addition, a planned 2:30 p.m. 30-minute Pan-American Day speech by Cordell Hull, the U.S. Secretary of State, from the New York World's Fair was rescheduled to the next day. (The speech would have pre-empted the usual weekly 2:30 p.m. 30-minute CBS network music program featuring Clyde Barrie and the Leon Goldman ensemble.)

|

3:00 PM

(10 min.)

|

Follow-up interviews

|

Local programming:

News analysis and interviews

|

Unsponsored

|

Follow-up interviews by CBS's Albert Warner for WJSV with Rep. William B. Bankhead (Speaker of the House), Rep. J. William Ditter, and Rep. Mary Norton<.

|

3:10 PM

(15 min.)

|

The Career of Alice Blair

|

Local programming:

Syndicated serial drama (transcribed)

|

Daggett and Ramsdell cold cream

|

Postponed from its usual 2:00 p.m. D.C. airing.

Network note: The local WJSV programming which ran from 3:00 to 3:45 pre-empted both a CBS network's sports special airing of the Mont d'Or Handicap handicap horse race at Belmont Park plus the CBS network's Alabama Polytechnic Roundtable, a special broadcast featuring a discussion between agricultural and manufacturing interests.

Today's story: Alice is wary of the neighbor with whom her uncle has tea.

|

3:25 PM

(5 min.)

|

Arrow News Reporter

|

Local programming:

News

|

Arrow Beer

|

Joe King of WJSV did the reporting.

Postponed from its usual 2:15 p.m. D.C. airing.

|

3:30 PM

(15 min.)

|

Rhythm and Romance

|

Local programming:

Transcribed music

|

Zlotnick the Furrier

Manhattan Laundry

The Women (1939)

|

Program's narration provided by Joe King (WJSV).

Postponed from its usual 2:20 p.m. D.C. airing.

|

3:45 PM

(15 min.)

|

Scattergood Baines

|

CBS network:

Serial drama

(transcribed from the previous day)

|

Wrigley's spearmint gum

|

Postponed from its usual 1:45 p.m. D.C. airing (as a delayed broadcast of the live 4:45 p.m. CBS airing of the previous day.)

Network note: This local WJSV broadcast pre-empted a CBS network music presentation of the Four Clubmen music program.

Today's story: A scheme to rid the town of a gambler continues.

|

4:00 PM

(77 min.)

|

Washington Senators baseball game—Cleveland Indians at Washington

(joined in progress)

|

Local programming:

Sports

|

Wheaties< cereal

|

Joined in progress in the last half of the 4th inning. The WJSV sports announcer was Harry McTigue and Walter Johnson did the play-by-play. Cleveland won 6-3, and a case of Wheaties was awarded to Washington player Charlie Gelbert for his 7th inning home run.

Network note: This local WJSV broadcast pre-empted several CBS network programs, which, according to other cities' listings from that day, began with Genevieve Rowe. The pre-emptions continued with Patterns in Swing, March of Games, Scattergood Baines< and the news with Edwin C. Hill.

|

5:17 PM

(13 min.)

|

The World Dances

|

Local programming:

Transcribed music

|

Equitable Credit Co.

|

Postponed from its usual 5:00 p.m. D.C. airing.

Network note: This local program pre-empted the CBS network's 5:15 p.m. news broadcast by H. V. Kaltenborn (CBS News).

|

5:30 PM

(5 min.)

|

Arrow News Reporter

|

Local programming:

News

|

Arrow Beer

|

Hugh Conover of WJSV did the reporting.

Network note: The local WJSV programming which ran this day from 5:30 to 6:00 p.m. pre-empted the CBS network's special religious broadcast, the .

|

5:35 PM

(10 min.)

|

Time Out

|

Local programming:

Organ interlude

|

Zlotnick the Furrier

|

Performed on a Hammond electric organ by Johnny Salb, WJSV staff organist.

|

5:45 PM

(15 min.)

|

Goodrich Sports Reporter

|

Local programming:

Sports news

|

B. F. Goodrich

|

Reported by WJSV sports announcer Harry McTigue.

WJSV note: Local newspapers continued to cite the name of the previous host, former WJSV sports announcer Arch McDonald, in their daily radio listings, even though McDonald had left D.C. to broadcast baseball games in New York (he would return after a single baseball season.)

Network note: This local sports report would normally pre-empt CBS's Judith Arlen's Penthouse Blues.

|

6:00 PM

(15 min.)

|

Amos 'n' Andy

|

CBS network:

Serial comedy/drama

|

Campbell's Tomato soup

|

The network feed of this show had an initial 3-minute gap which was covered locally by a transcribed organ interlude.

Today's story: Complications arise over a singing recital.

|

6:15 PM

(15 min.)

|

The Parker Family

|

CBS network:

Comedy

|

Woodbury facial soap

|

This week: Junior mistakenly believes his parents are divorcing. Hilarity ensues.

|

6:30 PM

(30 min.)

|

Joe E. Brown

|

CBS network:

Comedy/variety

|

Post Toasties cereal

|

Comedy sketches and music. With Frank Gill and Bill Demling (Gill and Demling), Margaret McCrae, Paula Winslow, and Harry Sosnik and his Orchestra. The announcer was Don Wilson<.

|

7:00 PM

(30 min.)

|

Ask-It Basket

|

CBS network:

Audience quiz

|

Colgate dental cream

|

Four contestants were selected from the audience. A sailor, a student, a stenographer and a department store buyer competed for cash by answering questions sent in by the radio audience. Hosted by Jim McWilliams.

|

7:30 PM

(25 min.)

|

Strange as It Seems

|

CBS network:

Human interest

|

Palmolive shave cream

|

Stories were told that ranged from the unusual to the inspirational. The show was based on the cartoon panel of the same name. Hosted by Alois Havrilla<.

|

7:55 PM

(5 min.)

|

Elmer Davis and the News

|

CBS network:

News

|

(Sustaining)

|

Today's war-related news.

|

8:00 PM

(60 min.)

|

Major Bowes' Original Amateur Hour

|

CBS network:

Talent contest

|

Chrysler products, this week featuring the new 1940 Plymouth<

|

This night's contestants consisted of an assortment of musicians, vocalists and one young tap dancer. This week's designated "honor city" was Mansfield, Ohio. Bowes read a profile of the city, and Mansfield residents had a dedicated phone number for voting.

Note: The performance of "Over the Rainbow<" was one of several musical numbers heard on this broadcast day which came from the just-released The Wizard of Oz movie.

|

9:00 PM

(30 min.)

|

Columbia Workshop Festival

|

CBS network:

Radio play

|

(Sustaining)

|

This week's episode, part of the Workshop's third annual summer festival, featured Now It's Summer, an original radio play by Arthur Kober.

Network note: The radio play originally planned for this date was Timothy Dexter by J. P. Marquand. Coincidentally, Dexter's unusual dealings were profiled earlier in the evening on a segment of Strange as It Seems.

|

9:30 PM

(30 min.)

|

Americans at Work

|

CBS network:

Educational

|

(Sustaining)

|

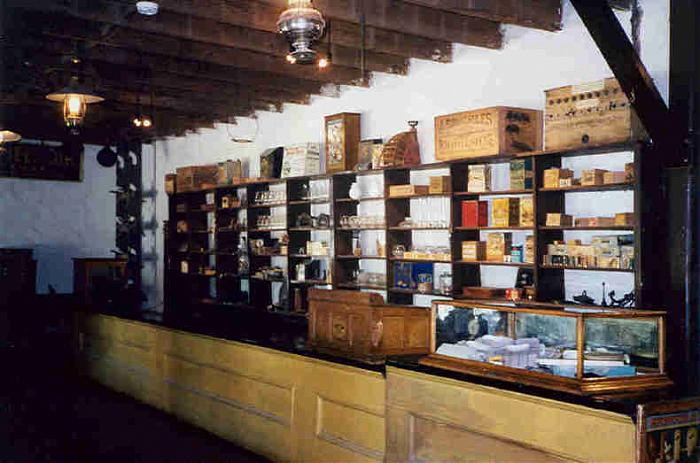

This series was presented by the CBS Department of Education as part of CBS's Adult Education Series. This week's episode explored the work of five different auctioneers.

Network note: This episode had initially been scheduled for Saturday, September 23.

|

10:00 PM

(5 min.)

|

Arrow News Reporter

|

Local programming:

News

|

Arrow Beer

|

Hugh Conover of WJSV did the reporting.

|

10:05 PM

(10 min.)

|

The Human Side of the News

|

CBS network:

CBS news

|

Amoco gasoline products

|

Reported by Edwin C. Hill.

Updates on the war in Europe.

|

10:15 PM

(15 min.)

|

Streamline Interlude

|

Local programming:

Transcribed music

|

Zlotnick the Furrier

|

Network note: This local program pre-empted the CBS network's presentation of Cab Calloway's Orchestra.

|

10:30 PM

(15 min.)

|

Mid-Week Review

|

Local programming:

News analysis

|

(Sustaining)

|

Presented by CBS's D.C. correspondent, Albert Warner.

Note: In spite of Warner's network connections, program listings show that this was a local weekly program< which pre-empted the first half of CBS's presentation of Hal Kemp's Orchestra.

|

10:45 PM

(36 min.)

|

Rebroadcast of President Roosevelt's address to a special session of Congress

|

Local programming:

Political speech

(transcribed)

|

Unsponsored

|

Network note: This local rebroadcast pre-empted the second half of the CBS network's presentation of Hal Kemp's Orchestra, and most of the subsequent CBS program, Jerry Livingston's Orchestra.

|

11:21 PM

(9 min.)

|

Jerry Livingston's Orchestra (joined in progress)

|

CBS network:

Orchestra remote

|

(Sustaining)

|

Joined in progress with 9 minutes remaining.

Originating from Mother Kelly's Miami Room in New York City.

|

11:30 PM

(30 min.)

|

Teddy Powell's Orchestra

|

CBS network:

Orchestra remote

|

(Sustaining)

|

Originating from the Famous Doornightclub in New York City.

|

12:00 AM

(30 min.)

|

Louis Prima's Orchestra

|

CBS network:

Orchestra remote

|

(Sustaining)

|

Originating from the Hickory House in New York City.

|

12:30 AM

(25 min.)

|

Bob Chester's Orchestra

|

CBS network:

Orchestra remote

|

(Sustaining)

|

Originating from the Mayfair Restaurant of the Hotel Van Cleve in Dayton, Ohio.

|

12:55 AM

(5 min.)

|

CBS News

|

CBS network:

News

|

(Sustaining)

|

Presented by George Putnam, CBS news correspondent.

|

1:00 AM

(3 min.)

|

Weather / National Anthem / Sign-off

|

Local programming

|

|

|

Low Pass Filter

Low Pass Filter