Independent Authors

Dateline:February 15, 2021

Book reviews published in the Attic of Gallimaufry, and elsewhere.

The publishing business has changed beneath our anxiously tapping fingers, and rapidly reading eyes. We are part of that destructive change we often hear about. Waves of syllabograms have bypassed publishing's dues-paying gatekeepers in a Johnstown flood of self-published beastsellers.

Many readers ignore the torrent, preferring the guidance of reviews found in newspapers and magazines, but many have breasted the maelstrom to sample its unregulated flow of tyro creativity.

Finding a worthwhile book in this fire-hose stream can be as frustrating as finding a pony in a stable-hand’s work product. Advice abounds and help is inventing itself. This page looks at how things are going, from the reader's viewpoint, and the writer's.

Let's start by acknowledging, things are grim. The small sample of Independent writing reviewed, or side-glanced, by the Gallimaufry Experts (an anonymous team of concerned citizens and self-styled critics), points to a few observations that come close to being laws of nature.

First Principles of Self-Published Writing

- Most self-published writing is awful (unreadable), chock-full of garbled construction, disorganization, and incoherence. Then there are the plot, character, and setting clinkers. Please. Hire an editor. Really.

- The most-read DIY publications are self-help efforts targeted at popular problems (For example, how to be successful as an independent author).

- The most-read, self-published fiction is genre-directed, e.g. Crime, Romance, Science Fiction, for which a tabloid-like market is scanning the horizon.

- Non-genre fiction and non-self-help non-fiction are bottom dwellers. No one is waiting for, nor seeking out, the magnum opus of Elm Street.

- Getting noticed is the first problem of a self-published author. Unless the author already has a following from some other activity, advertising is essential.

- Social Media, the free stuff, does not build recognition at a rate useful within the span of a human life. It can amplify, but does not generate, interest in non-graphic art.

- Facebook is not full of readers. It is full of amateur writers.

- The self-published author writes for the experience of writing, and publishes because that's what comes next after writing. That's the good news.

We've included some links to various online resources specifically aimed at the independents. They have some useful ideas about how to set up your word processor to get that manuscript in decent shape, some thoughts about other publishing tools and services, and, of course, a couple of links to organizations that say they're the friend of the Independents.

We have a few reviews of some independent authors, as well as some old-fashioned, High-Church authors, who have made a positive impression. Selection is, of course, a matter of taste, and these are among the best we've found. If you find your taste compatible, we welcome your reviews of Independents you've enjoyed. If they pass mustard (see what I'm saying about editing? By the way, please do not confuse "defuse" and "diffuse." Just saying.) we'll post them here.

We'll even see if we can find one of our colleagues interested in reviewing your book, if you like. We post our reviews here, on Amazon and on Goodreads. Check back to see what else might siphon out of the whirlpool and land here.

Self Publishing Resources

First off, here's the authoritative how-to-do-it. Miblart's blog gives us the skinny on how the toothpaste gets into the tube, self-publishing wise, all up to date and shinny new for 2021. If you're reading this later in the decade, I'm sure someone has done an update. It's good to have a checklist. Thanks, Miblart.

Anne R. Allen and Ruth Harris get us right up to date on where self publishing has gone over the last decade. It's nice to get a clear perspective going into the 2020s.

Here are things to avoid when you self-publish, brought to you by BookBaby Blog. No, avoiding self-publishing is not one of them.

Many authors use Scrivener as their composition tool, instead of a word processor. Scrivener has some powerful conceptualizing and organizing tools, and it is friendly to self-publishing formats.

Susan Russo Anderson has a blog entry on how to use Scrivener for self publishing.

David Gaughran runs a blog on self-publishing. You can learn the process and get pointers on formatting, and other mechanical matters. He will also give you some criteria for making various self-publishing decisions.

Jane Friedman also blogs on self-publishing, and provides links to extensive how-to, and self-help resources. She provides advice, editing, coaching, publishing and marketing help. She gives helpful advice on choosing an E-Publishing service.

Greg Standberg's Big Sky Words blog provides some key information about getting a cover on your book. The cover might be your most important selling point. It is certainly the first thing anyone will notice about your book. Here are some things to think about.

Okay. Finally. This is it. The horrible hidden truth about self-publishing that nobody wants you to know.

Ok, Okay, OK. Now it's your move, and here's your template.

Once upon a time...

...insert your stuff....

The End

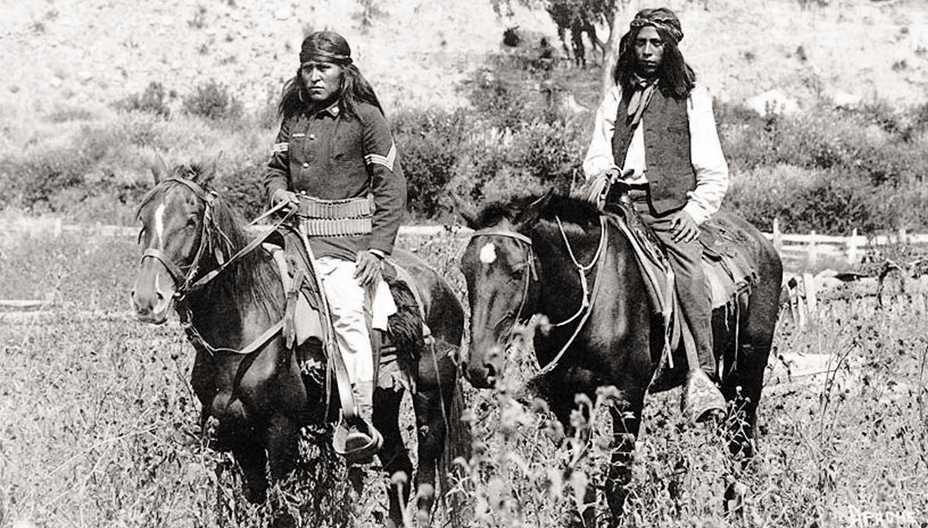

A Review of Arley Dial's "Nagodzaa: A Warrior's Elegy",

Human Passage in the New World, by Gregory S Trachta

By 1880, European immigrants, enabled by their social institutions and technology, had largely displaced the stone-age inhabitants of the current United States. That is the likely year of the novel, Nagodzaa: A Warrior’s Elegy, by Arley L. Dial. It is a believable, highly readable, and engaging snapshot of this transition’s end game in the Arizona territory. Mr. Dial moves smoothly between points of view, taking us inside the feelings and thoughts of cavalry soldiers, both white and black, Indian agents, Apache scouts, Mexican vaqueros and Apache warriors. You’ll find heroes and villains, desperate fights, love, hate, horrors, humor, justice of a sort, even a cavalry charge, but this is not a Hollywood treatment. Don’t expect noble savages, heart-of-gold cowboys, or John Wayne soldiers. When we hear the Apaches talking and thinking there is no, “Ugh-How-Me heap Paleolithic philosopher,” language, although his sparing use of Apache vocabulary and names is effective. Nor, are the Native Americans simply white men wearing scanty clothes. Mr. Dial works from the basic humanity of his characters, and gives us their words, thoughts and deeds from within the context of their culture. Even the bad men, and they are very bad indeed, come to us as human beings working from different motivations, morals, and social values.

To the Europeans, the indigenous tribal-groups were at best a religious challenge and at worst a dangerous nuisance. To the aboriginal Asian immigrants, long established in the New World, the Europeans were a befuddling menace, against whom they fought a lingering and fragmented war, until finally overwhelmed around the end of the nineteenth century. The progress of European, now called American, settlement accelerated after the founding of the United States. By the end of the Civil War, in 1865, the so-called American Indians had been neutralized in all territory east of St. Joseph Missouri, along most of the Pacific Coast and in a large swath through much of Montana, Idaho and Utah. Fifteen years later, at the time of this story, they had been pushed or starved onto reservations, except for some undervalued areas in the current states of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and the Dakotas. The world of the indigenous tribes was coming to an end, the evident meaning of the book’s title.

As with his previous novel, Plews, Mr. Dial is at his very best in giving us the climactic battle scene. It is a dirty, gritty, horrifying event with little romance and utterly no mercy. If you’d like to form an impression of what it felt like to be alive in 1880, living in the American Southwest, whether white, black, Indian, or Mexican, this book will help you. If you just want a good, well-researched read that faithfully reconstructs and presents an historical period, this is your book.

A Review of Arley L. Dial's Historical Novel, "Plews"

In the footsteps of Lewis and Clark, by Gregory S Trachta

When demand for beaver hats decimated the populations of Castor fiber in Europe, traders turned to the New World and its similarly chapeau-worthy Castor canadensis. In north America the pelts were called “plews,” from the Canadian French, “pelu,” meaning hairy. In 1825 the Rocky Mountain plew trade was organized south of the Platte River around a business model called the rendezvous scheme. But in 1819, the evident year of, “Plews, ” a novel by Arley L. Dial, the fur trade in America was still dominated by the Upper Missouri trade, as it had been for a hundred years, controlled by companies in the east.

It was a pregnant moment. Business was just recommencing after the War of 1812. Steamboats, navigating the Mississippi since 1811, were turning St. Louis into a major trading city. Missouri was just a few years from statehood. The panic of 1819, instigated by the production of India cotton, which brought on a collapse of cotton prices, which created a liquidity problem at the Second United States Bank, caused money to disappear. Desperate men sought desperate means, and poaching into the Upper Missouri trade looked attractive.

Mister Dial has written a rough and tumble account of an expedition, from St. Louis to the Missouri headwaters, to trap beaver and trade with the Piegan Indians, a southern branch of the Blackfoot nation. His carefully researched yarn unspools in a believable evocation of the era. Readers may be surprised to learn that the Mandan Indians practiced agriculture, including cultivation of corn and vegetables. We glimpse them, and others, just before the plains wars, and white-man diseases, drove them into extinction, or onto reservations. The Mandan were devastated in 1819 by measles and whooping cough.

Mr. Dial takes us into the era through the eyes of his characters, a believable collection of seasoned mountaineers, boatmen, green horns, sadists, cowards, heroes, sea pirates, misfits, traitors, opportunists, and even a free black man, mixed in with various indigenous people rendered surprisingly human rather than as Hollywood cutouts. They forge an intriguing improvisation of struggles, failures and successes.

We see boatmen laboring against the spring floods to get a keelboat upriver. Others of the group march along the banks with a band of horses and mules, hunting and meeting exotic animals. Mr. Dial gives us one of the most convincingly horrible bad men ever to populate the American frontier, and his evil scheme, half business, half personal, haunts the band of trappers to the climax.

The youth of some characters, one boy is only fifteen, and some are barely sixteen, is true to the times. At sixteen Abraham Lincoln operated a private ferry service on the Mississippi and at nineteen he took a barge of trading goods down to New Orleans. A contemporary, Lewis H Garrard, went down the Santa Fe Trail at seventeen with some Rocky Mountain traders, and lived to write a book about it.

Mr. Dial is at his absolute best in the wilderness of the Three Forks area as the climax comes amid Indian attacks, treachery, cruelty and triumph. We struggle with the characters through hair-raising battles, winter storms, grizzly encounters, ambushes, numbing calamities and death. One of the survivors, a sixteen year old we meet at the beginning of the book, becomes, by the end, a man with mountains in his veins.

A Review of Frank Scozzari's "The Wind Guardian"

What can go wrong will go wrong, unless someone prevents it, by Gregory S Trachta

“The Wind Guardian” interweaves the reader into the action, inside, and within the environs, of Mal Loma, a nuclear power plant evocative of the Diablo Canyon plant near San Luis Obispo, California. The story comes at us so deeply immersed in the minds of key characters, that one almost roots for the bad guys.

Nuclear energy produces the cheapest electricity, with the smallest carbon footprint, but it risks appalling consequences: fatal radiation and nuclear explosion. Much is done to control the risks, but is it enough? What if someone sabotaged a nuclear power plant? “The Wind Guardian,” by Frank Scozzari, Published 2015, by Creativia, explores that very question.

This is no made-for-TV shoot ‘em up, although there is ample shooting and vivid imagery. The book rests on well-researched detail about setting, weapons, machinery, security routines, and bureaucracy. The work practices and relationships within the nuclear facility are convincingly real. The characters have complex backstories that come out in bits and drafts as needed by the plot. The geography, including its archeological history, is itself a character, playing a providential role in the drama. There is even a walk-on, almost a speaking, part for the memory of the Chumash Indians, whose pre-colonial range was on the California coast.

They are all here: the well intended, the experts-at-what-they-do, the screw-ups, the mindless bureaucrats, the mercenaries, the ideologues, the spirits of the long dead, and the lovers. In the end, as with the narrative of life, chance becomes a significant player, thwarting some efforts and enabling others. Read this book for its drama and human insight, and learn a little something about living with unthinkable risk.

A Review of Dave Shiflett's "In the Matter of J. Van Pelt"

Just when you think you've got it all figured out...uh oh, by Gregory S Trachta

Think about Roy Blount Jr. channeling Socrates. Think about a Robert Benchley sendup of Erskine Caldwell. Think about Jack Davis, 1950s Mad Magazine cartoonist, with his antic detail, sinuous distortions, and absurdity. Think about finding truth. Now, you’re ready to read “In the Matter of J. Van Pelt,” by Dave Shiflett, folk singer, political analyst, ghostwriter, and novelist.

Truth can’t be gotten head on. It doesn’t come in a tweet. It forms in the spaces between the things we know for certain. It emerges between the things we knew then, and the things we know now. When we’re sure we’ve got it, it flies into the jet stream, burrows into the earth, and warbles from the song of a cardinal.

Mr. Shiflett gives us the journal of the novel’s namesake, J. Van Pelt, who takes a long journey in his mind, and is taken for a short ride, by the outside world, in the way Jimmy Hoffa was taken for a short ride. Like the now unrepeatable vaudeville act of Stuttering Sam, he earnestly starts one way, falters, and pivots to the opposite with equal certitude.

Van Pelt is a middle-aged, over-weight, marginally successful toady in a Washington law firm, who senses his life is a drifting oblivion. He starts his journal to speak truths too dangerous to say aloud. His liberation is its secrecy. He reckons toward absolute veracity, without fear of censorship or condemnation. Mostly. But his truth keeps shifting. The elements of his life are bizarre. He plunges in, and day-by-day, certitude shifts like the wind, spiraling toward something, or flying off toward nullity.

There is a counterintuitive theory of comedy and tragedy which holds that comedy is the pessimistic art form, and tragedy the optimistic. Tragedy rests on the assumption that life has meaning, otherwise why care if bad things happen? Comedy assumes life is meaningless, or we couldn’t laugh at it. This book is funny. Seriously funny. The humor squirts out like milk from startled nostrils. It flies up like a rake handle between the eyes. It weaves on many levels in every line, threading its crazy-quilt narrative. But the humor does not describe a random universe of no consequence. It drapes from humanity’s essential structures, love, character, spirituality, memory and eternal longing, like the marble drapes of Callimachus, their wind-swept edges caught in mid flutter.

It’s all here. The enigma of conscious life, the tension between ancient and modern, the timeless longing of humanity, the nasty details of human interaction viewed up close, the impossibility of knowing the truth, and, yet, the possibility of catching a glimpse of eternal beauty wandering on her way. If all you get from the book is a good laugh, you’re ahead of the game. You’ll probably get something more optimistic.

Who in the world cares about writing?