Comments on Human Migrations?

The eruption of Mt. Toba, in about 74,000 BCE, caused a 6 year winter and 1000 year ice age, reducing the human population to about 10,000 adults. Hmmm. Maybe not. This often mentioned result is now being rethought.

Check it out in the link from the above picture.

This video of the history of world population (since CE 1) is provided by the website "World Population History." Check out the site for more analysis.

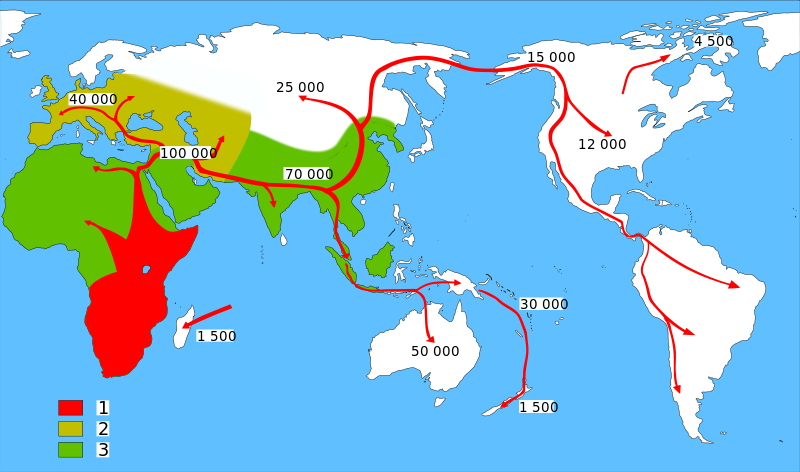

Recent discoveries in the analysis of ancient DNA have yielded surprising conclusions about how we all got where we are and about who has the best claim on being a native in the region they currently occupy. The above link gives the classic theory, as of about ten years ago.

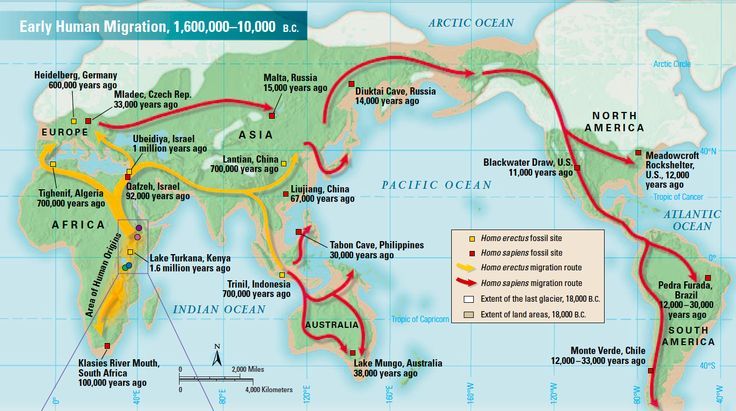

At that time the state of scholarship on Paleoamericans, the first human immigrants to this continent, was summarized by"James Q. Jacobs," Anthropologist/Archeologist, Academic Instructor. His analysis is linked below.

Studies at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, which analyzed the DNA of the well preserved Kennewick man whose skeleton was discovered in Washington State, and some human DNA from Siberia, have brought a new dynamism to theories of human migration. Read about this work at the The Wall Street Journal, and in the journal Nature. Alternate takes on this new information are presented by Nature and The Guardian.

Several recent studies on European and New World migration have documented more massive,and more recent migrations than had been previously suspected. BBC news recently discussed the link between migration and language development about 4,500 years ago. They had previously discussed some of the puzzles solved by recent dicoveries. Further information on the so-called Kostenki man can be found at the University of Cambridge, and yet another discussion of human migrations was published inThe New York Times.

Our understanding of human migration to America is being revised rapidly. The picture links to a recent study of South America, and the video below discusses the Americas in general.

Or, if arm waving isn't your style, try this one by Khan Academy.

The Monte Verde archaeological site in Chile has long been the laboratory of Dr. Tom Dillehay. Tom earned his Ph.D. at UT, but is currently at Vanderbilt. He has been touching off debates about the arrival of humans in the new world for decades. He has just touched off a new one. Humans may have reached Chile by 18,500 years ago, an astoundingly early migration given that the land bridge from Siberia south into the Americas had only recently thawed enough to allow southward migration.

Tom Dillehay at Monte Verde as described at Anthropology.net.

Click picture for an interactive map showing the relationship between populations, historical events, and the resulting admixture of groups over the last 4000 years.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/4f/f0/4ff0ffdf-4239-40a0-93d5-6c3ec5dbd899/202468.jpg)

Click picture for an interview with Douglas Wallace on recent DNA evidence in the Americas.

If you're interested in a more technical discussion of the subject (prior to the latest findings), click the picture for a paper by PLOS Genetics.

The West Eurasian origins of American Indians has been known for a few years. Click the picture a National Geographic article on the subject.

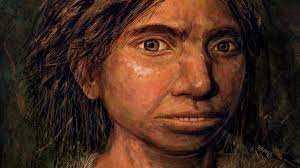

Ancient DNA has also revealed the existence of a hitherto unknown group of people called by researchers, the Denisovans. Scientific American wrote about them a few years ago and their relationship to modern humans and Neandertals.

Ancient DNA is also revealing trade routes and commodities previously unsuspected. For example, there is evidence wheat grain was imported from Europe into ancient Britain long before the advent of farming on the islands.

All of this research is bringing clearer explanations about how the transition from hunter/gatherer to agrarian societies came about.

Ancient DNA has revealed a return migration back into Africa, previously unsuspected.

Science 2.0 has published an article showing the relationship between new migration research and archeological research.

A link has recently been established between current Native Americans and the earliest known migrations into America.

Finally, a summary of news in ancient DNA research by Quanta Magazine.

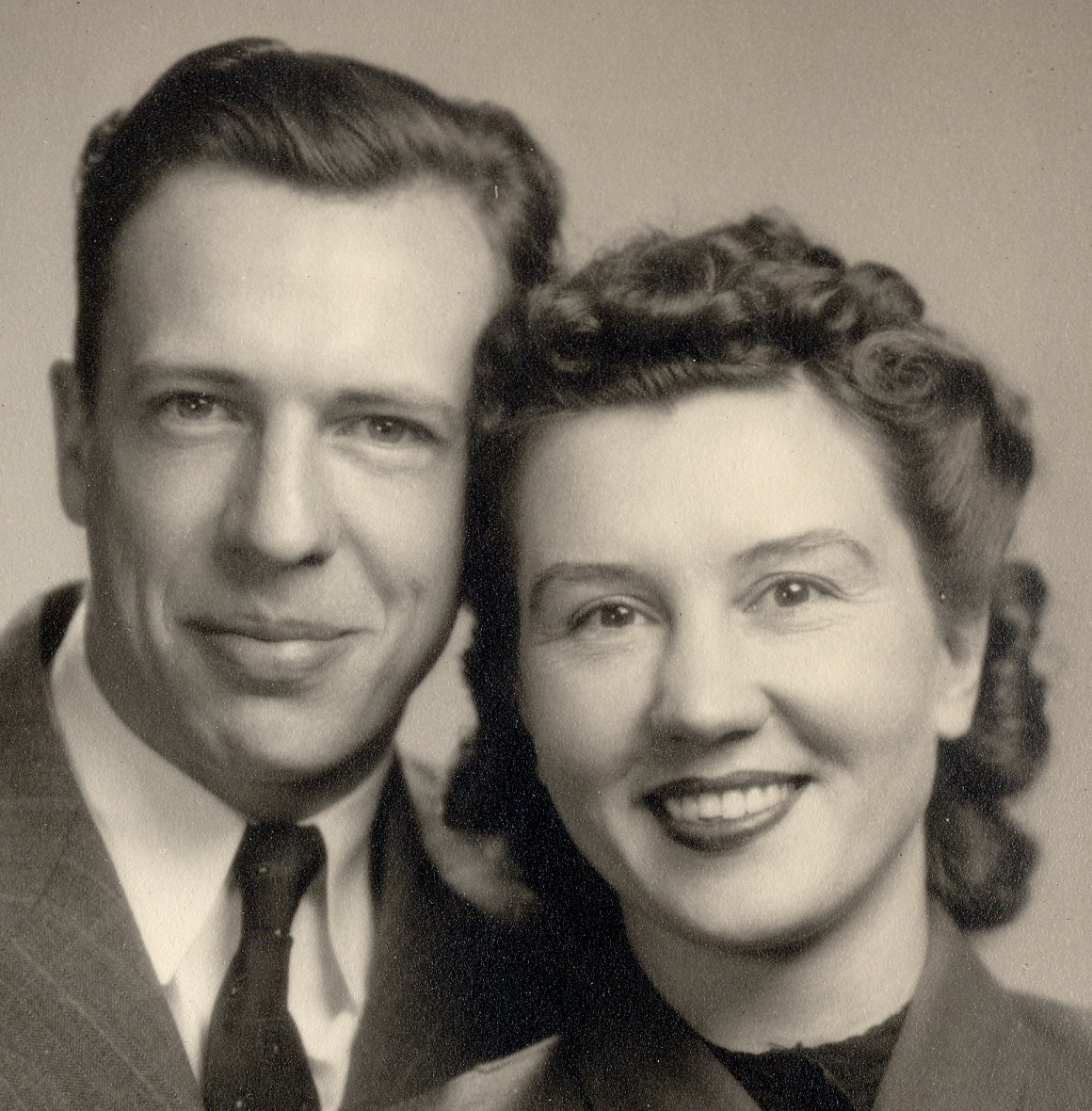

I met dad and mom when they were 27 and 26. This is how they looked then, and always. They were in the first years of a long adventure that began with World War II, and ended in the next millennium. They had lives before we met them, and even before they met each other, and their life with us was a continuation of their separate paths. But to us, their children, their lives were the normal order of the universe. I was far into adulthood before I realized how rare was their gift to us. There was never a day when I doubted their love and dedication.

Dad's ability to guess the shape of the universe from a minimum of data was his most important trait. It was reflected in his rapport with machinery, and apparently inherited. His own father was a oil driller from the days when holes were literally punched into the ground, and my father spoke in awed tones of his ability to, "grab the cable as it dropped the bit, and know how deep the hole was, the composition of the soil, and whether the hole was straight or slanted."

My own father was a machine healer, laying on hands. He knew how things worked, whether mechanical, electronic or theoretical. He could also, in later life, look out his front window in rural New Mexico, watch the traffic go by, and know what was going on in the neighborhood. "They've struck oil on the ___ place, but the well caved in when they got the mud wrong, so now they're trying to shore it up with casing." Or. "They've dropped the water table too low, and they can't irrigate anymore. They're selling out and moving to town." Every observation went into a working theory and all the pieces fit together. He wasn't always right, but he always converged toward the truth.

He suffered all his life from emotions beyond expression. He seems never to have had the necessary signals from his parents to be sure how they felt about him. "I thought there was something wrong with me," he confided, a few weeks before he died. His little brother, Eldy, was two years younger than him, and they were exceptionally close. Sometimes he talked about their years of living together when he was attending college, how they fixed up an old car together. During the war my dad was ineligible for the draft because of a football kneee. His older brother was at Pearl Harbor and made a career in the Marines. His little sister was a WAC. His little brother was a pilot, shot down over Germany in the war's closing weeks. Dad seldom spoke of any of this, but nurtured self-doubts and grief the rest of his life. Eldy was ever near the top of his thoughts. In his last year I was helping him with some paper work and needed the password to his computer. "Eldy," he told me.

Mother was reared by parents from rural Missouri. Their nineteenth century ancestors were products of the southern rural culture, and my mother was very close to them all their lives. Nevertheless, she somehow dodged their prejudices. The first, and most frequently voiced lesson Mother taught her children was the simple truth, "People are people, and you can never tell what someone is by looking at them or where they're from. In all groups there are good people and bad people, smart people and not-so-smart people, talented and untalented, hardworking and lazy. You have to get to know the person, not where they come from." How she acquired that knowledge is mysterious, because it didn't come from her parents. It was indicative of her inner self assurance. She was her own person, always, and she had the ability to make people accept her for who she was, not for who she was with. That legacy was her most important contribution to her children's happiness. "Don't worry about what someone thinks of you if you're doing the right thing. Those that matter will think well of you and the others don't matter." Heady stuff for a two year old to hear.

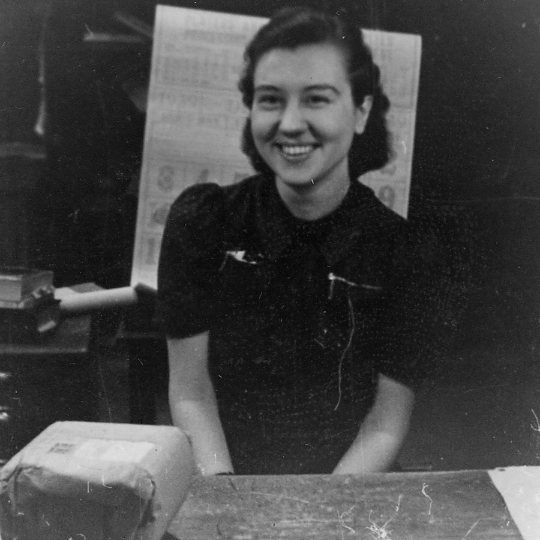

Dad was born in Meeker, Colorado, and spent his childhood following his father around the oil fields of Colorado, Montana and Wyoming. He graduated from the University of Montana and got a job with Standard Oil in Rawlins, Wyoming. That's where he met our mother when she was working in the post office. At her memorial service Dad remembered, "I was impressed at how kind she was. The migrant workers bought money orders to send back to their families, and she counseled them on how much they could afford to send and how much they needed to live on. I liked that and decided to see if I could get her. And I did. I got her."

We were always told mother was born in Cherry Box, Missouri, which sounded like a real place to youngsters. In fact she was born in a farmhouse near Cherry Box, which was little more than a post office. Her parents had trouble making a go of farming, and pulled up stakes in the mid 1920s for Nebraska. They moved around following work, and she graduated High School in Wyoming. She inherited the forceful personality of her Stasey ancestors, and their gregarious leadership nature. All her life, wherever she lived, in whatever circumstances, people knew her and valued her friendship. In her last years she would wheel through the halls of her assisted living home, stroke impaired and unable to walk or speak, to be greeted by everyone she saw, waving her one good arm, smiling and doing her best to offer a greeting. Indomitable. Unquenchable. When she passed away my first thought was, "She must have been ready to go, because if she wasn't, she wouldn't have." Everyone in the home, her latest batch of friends, attended her memorial.

Shortly after they were married, our parents moved to Richmond, California, when Dad got a transfer to the Richmond Standard Oil refinery. They were there during the war, Dad being deemed more valuable making gasoline than soldiering. After the war they followed the Stasey grandparents to rural Missouri. The motivation for leaving a well-paid job in his chosen profession, chemistry, for the uncertainties of farming, is ever a mystery. The standard answer to that question when it came from outsiders was Dad's health. He suffered respiratory problems all his life, from allergies and the after-effects of the 1918 flu. Maybe. But it may also have been Dad's lifelong aspiration of becoming a writer. Or, his desire to escape…from his brother's death, from questions about his war experience, from the mid-thirties blues, or from the daily routine of living. Anyway, he wasn't a farmer, and when his dad passed away, he threw in the plow and went back to professional life with Standard Oil. Those years on the farm are my go-to childhood memories, amazing formative years. I'm forever indebted to my parents for that experience.

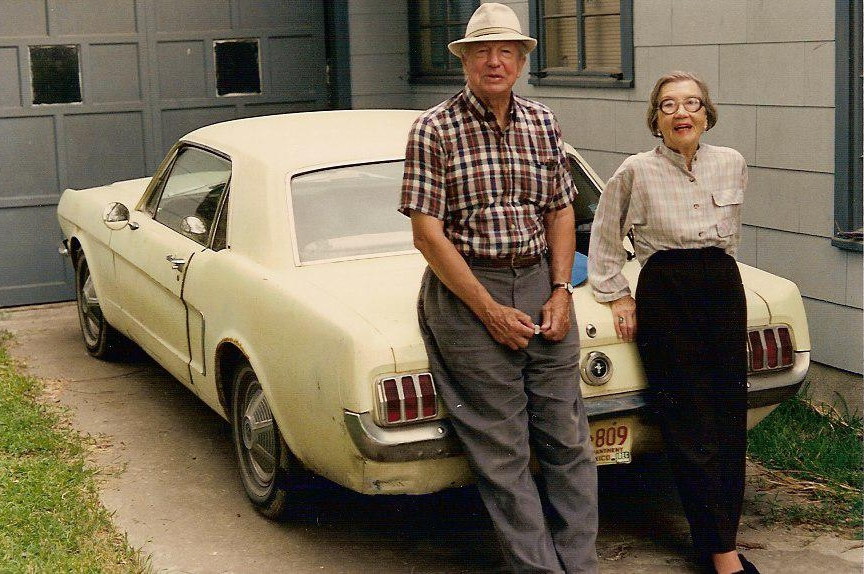

From Missouri the family went to Rangely, Colorado, where Dad's parents had retired and where his mother needed help, to Carlsbad, New Mexico, where he worked in the potash industry, to Hobbs, New Mexico, more potash refining, and then into a series of jobs in his later career that took him finally to Odessa, Texas. While in Carlsbad, during the 50s and 60s, they were active in church, Little Theater, Toastmaster/Toastmisstress, and other civic activities. After retirement they moved to a small acreage near Loving, New Mexico where they lived on a rocky outcropping of the former beachfront of the ancient Permian Sea, now desert from horizon to horizon. It had the advantage of low vegetation which suited what his sister Anne referred to as his, "snout." That is, his allergies.

In retirement, they again lived a rural life, but with the advantages of nearby civilization. Dad continued proving he was a better tractor mechanic than farmer, and pursued a leisurely retirement until it became physically impossible for them to continue. They sold up, moved to Austin, Texas, and lived in assisted living homes until they passed away in 2005, within five months of each other. Even there Dad had his collection of scrap metal and spare parts at hand, a tool box, and some heavily customized potty chairs and power scooters. A few days before he died he was modifying his scooter to improve its performance and get his oxygen bottle attached. I haven't visited their graves in Carlsbad in a few years, but I wouldn't be surprised to find some scrap metal stacked nearby, and perhaps an incoming power line. I'm sure he knows exactly what's going on around him, and I'm sure our mother has made friends with everyone.