Robert Lewis Gipson left us this memoir, posted to the Internet by a relative, Jane Wisdom,of Topeka, KS. The picture is of an 18th century cabin in North Carolina, that illustrates Gipson's description of his boyhood home.

Old people spin yarns. Others unravel them. What shall we make of Robert Lewis Gipson? He claimed to be the oldest man in the United States in 1884, when he "decided to have a few sketches of my life written." He was unschooled, so his story comes through an unknown collaborator. Gipson promised "nothing flowery, but just simply my words." Probably they are his words, mostly. Where does that get us?

He says he was born on Christmas day, 1766 in Randolph County, North Carolina. We know he died in Macon County, Missouri in 1886. That would make him 120 years old. If true, who could dispute his claim of being the oldest man in the United States?

His story got into the History of Macon County, Missouri, published in 1884, and they take his word for being 118 years old. The Internet begs to differ, citing discrepancies in U. S. Census records. They chronicle his receding birth year. In 1850 the census listed his age as 65 (birth year 1785). In 1860 his birth year drops back 1780. By 1870 it was 1778, and by 1880 it reached 1767. The older he got, the older he got. Some observers assume Gipson, who loved a good story, padded his age as contradictory witnesses disappeared. Probably true, but let's look a little further.

The shovel plow Gipson says he used for decades was probably similar to this one at Mount Vernon. The link is to a short history of the Plow.

In the census takings prior to 1880, the information probably came directly from Gipson, as he was the only adult in the household. His age wanders, but so does the age of his son, William. In 1850 William is listed as 22 (birth year 1828). In 1860 he's 26 (birth year 1834). By the way, in 1860 the census tags William with a disability: Idiot. Probably that's why he continued living with his father. In 1870 William is 40 (birth year 1830). By 1880 both Robert and William are living with Robert's son, Hezekiah, and the census information might have come from him. That's the census that has him at 113, and William at 60 (birth year 1820). The drifting birth year could confirm a propensity to exaggerate, or maybe he wasn't good with dates.

Gipson's first wife, Grace Smith, is said to have been born in 1794, although the provenance of that date is unknown. Genealogical researchers cite1812 as the year of their marriage, based on something called a "Marriage Bond" of that date in North Carolina. Gipson says he was married when he was 35. Others make it to be 30. You can't get to 1766 by subtracting either 30 or 35 from 1812.

Probably Gipson never gave much thought to age until people took an interest in him approaching the century mark. It is easy to hear the voice of an "aw shucks" braggart in his "sketches." If he padded his age by twenty years, or so, that makes him about 100 when he passed away on April 6, 1886. He may not have been the oldest man at that point, but it's pretty old for the time. Maybe we'll forgive him for imagining a few extra decades. What else do those sketches tell us?

He reports an amazing prowess at wrestling and fighting, even into old age, but let's pass over that. Story telling is addictive. Think what he might have claimed if he'd had an Internet. What did he tell us that our history books, and most storybooks, don't? "Uncle Bobby," as his latter day contemporaries called him, gives us a clear-pane window into an ancient "present moment." We get a sense of what it felt like to be alive in that primitive time.

This man in Winslow Homer's painting from 1865, is using superior technology to Gipson's earliest recollections of cutting wheat with a sickle. He never saw hay, he says, until the invention of the mowing machine. The picture links to a sort history of hay in America. It suggests there was hay being made in America in Gipson's youth, but not much. It largely supports Gipson's recollections.

Some of the details he surely lived for himself. Some he may have "inherited" from the adults of his youth. Take that claim of having voted for George Washington. Some Internet observers accuse Gipson of bloviating, because there was no popular election for Washington. They're probably right about Gipson, but not Washington. There was a hastily organized popular election in December 1788 (polls closed on January 10, 1789). Electors were chosen and the Electoral College voted unanimously for Washington, as had been expected. Slightly more than 43,000 votes were cast. None came from North Carolina, where records place Robert Gipson until at least 1837, because North Carolina had no electors. The future State had not yet ratified the constitution. Gipson did not vote for George Washington in 1789, and probably not in 1792 either, since he was probably only about seven years old.

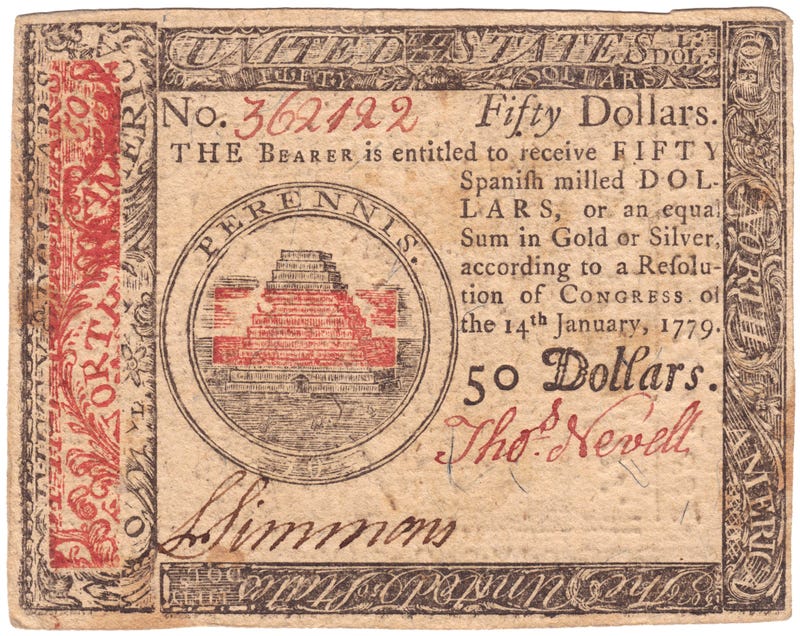

Gipson tells us no one had any money during his childhood. The currency and coinage situation in Colonial America was chaotic, and the chaos carried well past the presidency of John Quincy Adams. Click the image for a currency history.

What we likely hear in Gipson's claim is the voice of the zeitgeist of his youth. Everyone wanted a link to George Washington, the most famous man in the world. Cultural residue of his parent's generation may account for several items in his sketches, and where his experience emerges from theirs has become murky. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. His testimony sounds authentic, and gets us within a generation of the action. That's better than most books, movies, graphic novels, or Facebook postings.

Uncle Bobby was a farmer. He used a shovel plow in his youth. The introduction of the wooden, moldboard plow left him in "wonder and amazement." He says he was forty-five when he first saw it. He is probably referring to the plow designed by Thomas Jefferson and tested in 1794. Local histories document its introduction into Midwestern farming between 1830 and 1850. Depending on which date of birth we assume for Gipson, he started using the moldboard plow in 1811 or 1830. Either date is plausible; so let's pay attention to his reaction. This man's dinner came from his hands, and he is as enthralled at Jefferson's innovation as we are at the iPhone.

He gives us a technological progression of the moldboard plow, and beyond. At first it needed a man, a boy and a horse to operate. The plow tripped frequently out of the ground, and required cleaning with a stick carried for the purpose. Several decades later came the Kerry plow, better, but not good. At last he used the Diamond Plow. Gipson, we learn, plowed twice as much ground with the Diamond plow as the Kerry, and three times as much as with the moldboard, which was incomparably better than the shovel. The Diamond plow more than tripled his economic value.

When most of us think of early farming we get images of wagons, haystacks, and, if we're straining for historical context, a team of horses. Uncle Bobby predated all of that. At least, his familial memory did. He remembers the first time he saw a wagon. Think of it. The icon of westward migration, and it didn't exist in his youthful experience. It wasn't pulled by a modern team, but by two horses in line. The driver rode the first and led the second. Gipson refers to a "check line" as a major innovation, unknown at that time (and largely unknown to us). The check line connects each rein to the opposite horse, allowing them to work in tandem. The entire theory and practice of harness, specific adaptations for special tasks, was the subject of volumes in 1900, and is as unknown today as building pyramids.

Prior to the introduction of wagons, sleds were used. They worked reasonably well in snowy country. Not so well elsewhere. Uncle Bobby tells us the main obstacle to wagons was their price, $50, at a time when there just wasn't any money.

By the way, it's become fashionable to reduce the horror of the Dark Ages; to reinvent them as a period of mild duskiness. This may owe to the increasing difficulty for PhD candidates to write something new about that period. If you encounter such reengineering of the fall of civilization, keep this in mind: when Rome fell, wagons disappeared. They didn't come back to Europe until the sixteenth century, and were not widely used for agriculture until the nineteenth. That's pretty dark indeed.

How did Uncle Bobby remember harvest time? Grain was separated from chaff by cutting it, piling up the stalks, and threshing them with willow limbs, made limber for the purpose. Later, the resulting mass was dropped repeatedly through a breeze manufactured by two men waving a sheet, and the seeds collected on another sheet as the stems and chaff blew away. Mowing machines were another wonder of Robert Gipson's recollection.

Today, a retrospective painting of early rural life must include a haystack. Robert Gipson says he didn't see one until he was thirty-five years old, because there was no hay. He used a reap hook (what we now call a one-handed scythe), for cutting grass, and it was too inefficient to make hay. He tells us the scythe and cradle replaced the reap hook, and the mowing sickle replaced them all. After the mowing sickle arrived, people began making hay. We know the scythe and cradle came into general use in America between 1800 and 1840. The horse drawn reaper, or mowing machine seems to have come to America via Peter Gaillard in Pennsylvania, around 1812. When it reached Robert Gipson depends on where he was living at the moment it caught up with him, North Carolina, Kentucky, or Missouri.

Uncle Bobby gives us plenty of reason to be glad we don't live in the time of his childhood, and yet, he maintains, "I enjoyed life better, and made a living easier." One reason he gives for this judgment is the lack of want, because there was nothing to want. There were no stores, no money, and nothing people couldn't provide for themselves. It was a simpler time. Does this sound familiar? Our present age longs for the simpler life now buried in history. Psychologists tell us this is simply a longing for the innocence of childhood, the Peter Pan impulse. It seems to have afflicted the human species for a long time.

After deploring the "painted ladies" of his later years, and the fashions and money spent on clothes, Gipson gives us a wonderful description of the clothing of his youth, all home spun from hemp grown nearby. He wore a "hunting shirt" made of buckskins, hemp or flax. His wife's wedding dress, flax-filled cotton chain. The cotton was ginned and spun by hand. Parties were organized to pick the seeds from the cotton. He never saw a "piece of store goods" until after he was married. Someone showed him a "piece of calico." It "put the spirit of pride" in the farmers, and those who could afford it were "stuck up." Imagine the degeneracy!

Gipson tells us he took very little medicine in his life, and attributes his good health to that fact, plus his diet. Medicine in 18th and 19th century American has gotten some bad press. The picture links to a history of alternative medicine in early America. Maybe Gipson was right.

In his childhood he and his neighbors lived in one-room log cabins. There were no stoves. Uncle Bobby saw his first stove at age fifty (probably around 1835). The fireplace had a wooden chimney. The furniture was a couple of beds, some trundle beds, a table, a few chairs and a shelf. Nothing there to stimulate pride.

We get one anecdote of his courtship days, involving a group of young people, a rising creek, and the necessity for each boy to carry his girl across to safety. The incident made a great impression on Uncle Bobby, and takes up several long paragraphs. More column inches than wagons, harness, hay, and plows combined.

Around age twenty, Gipson joined a team of drovers, and helped get a herd to New Orleans. It was his first time away from home. He made five dollars, and was swindled out of it almost at once. He gives us a long dissertation on entertainments of his youth, much of which involved butchering hogs, shooting matches, and wrestling. The wrestling sounds pretty violent, and occupied him well into his old age. We hear a little about his family. His first wife died when he was seventy, and he describes the marriage as loving and happy. He then married a widow but she later decided to move out and live with her children. He says this second marriage was not for love, but convenience. Maybe it was more convenient for him than her.

Beyond wrestling, Gipson's passion seems to have been horse racing. He gave up the practice after a near-death experience involving a runaway horse and a staked fence. He recounts several other narrow escapes from the reaper, all involving horses, or wagons.

One question anyone of great years will be asked is the secret of longevity. Gipson attributes his to having learned early in life how to eat, not too much at a time, and to be mindful of what upset him. He also learned early on how to keep his feet dry. We get the picture of a man who listened to his body, and learned to avoid overtaxing it with cold, and damp, and fatigue. He'd "used" coffee since it had become available, around 1812. He avoided tobacco until the preacher explained to him how to chew properly, and he became quickly addicted. He tells us to avoid this mistake, but is sure of the benefits of alcohol.

There is quite a lot more to learn from Uncle Bobby. He gives us one of those brilliant American, backwoods tales, this one involving cross-dressing, fighting women, a desperate flight from danger, infidelity, and a finger-biting, eye-gouging battle. He gives us a feeling for the westward migration, from North Carolina, to Kentucky, to Missouri. We see homesteading, hunting techniques, the prices of livestock, and the pleasures of life.

What concerned Uncle Bobby in his old age? You'll never guess, or maybe you will. The nations youth, you say? Right! The youngsters of his later years were failing to meet his expectations. The generation we look back to as the purveyors of the right stuff, was itself the despair of the oldest man in the United States.

At some point along the way, Gipson got religion and joined the Baptist church. He "put off the old man and all his deeds, and put on the new man." He became a lay preacher, and gives us a last chapter on faith, and fidelity to God. He leaves us with a prayer, which is not a bad closing for the last man to vote for George Washington.

Contributor: Jane Wisdom, Topeka, Ks.

I am enclosing this attachment for anyone that would like to have it.

Robert Gipson lived to be nearly 120 years old, living in Macon, County, Mo.

He is my gggg grandfather. His father was Stephen, and Stephen's father, Isaac, came from England.

Robert Gipson had 16 children. His son, Stephen was my ggg grandfather, buried College Mound, Mo. Stephen served on the first Grand Jury in Macon, Co. and he was a board member of the first board for McGhee Presbyterian College in College Mound, Mo.

The college closed in late 1800s after the railroads changed transportation routes.

College Mound was a thriving city when it was on the Stage Coach Line. Have fun, it is a piece of history.

Memoir of Robert Lewis Gipson-Original Print, Good Way Print, College Mound, Missouri

Thinking it would be interesting to the people of America to have a few words from the oldest man in the United States (unless they can get ahead of one hundred and eighteen years old) I have concluded to have a few of the sketches of my life written, and as I have no education, there will be nothing flowery, but just simply my words from time to time during the year of 1884, that year being my one hundred and eighteenth year.

I was born in North Carolina , in the County of Randolph, on the 25th of December, in the year of our Lord, 1766. At the age of 35 I married Gracie Smith, and by her had sixteen children. I now have at this writing, one hundred and five grand-children. And one hundred and ninety great -grand children, and ten great-great-grand, making in all of children, grand children, great-grand, great-great, three hundred and twenty one.

I voted for George Washington for president, and have voted in every presidential election there has been since. The last one I voted for was Blaine in 1884. I was brought up on a farm, which occupation I have followed from my child hood up to the time I quit work. That was not until I was 106 years old. I have always taken great delight in farming, but when I think of the kind of farming tools that were in use in my boyhood, and then think of those in use now, I am struck with wonder and amazement why, the only plow that was in use in my boyhood, was the shovel plow, and they were not one-half as good as they are now. But we broke up our ground and put in our crop and cultivated it all with the shovel plow. What would a boy think now if his father was to take him out to a ten acre field with one horse and an old shovel plow and tell him to go ahead and break it up. Why, if he was not a boy of great resolution, he would tell him that he could not get it broke up in time to put the corn in this year. That was all the way we had of breaking up until I was about 45 years old. I recollect well the great excitement and re-joicing there was when the old wooden mold-board plow was invented and came into use. The people thought this was plow was the greatest plow in the world, and it was the best the country afforded at that time. When it first came into use it took a man and a boy and a horse to use it; for there was no such a thing as a check-line in the country, nor men driving two horses hitched up together, only by riding one and leading the other. The boy rode and drove, and if he ever went three steps without the plow catching dirt he was lucky. But we had our little paddle hanging to our plow handle, and when our plow would catch so much dirt that our team could hardly pull it, we would stop and clean it off.

This plow was in use, I think about forty years. The Kerry plow took its place, and was a great deal better. There is, I suppose, many living now that recollect when the Kerry plow came into use. It would be considered of no account now, and in fact they are of no account at this time. They were looked upon as being a great plow, when they first came into use. The Diamond plow took their place, and if the people had broken up their ground as many years as I have with the shovel and mod-board and Kerry plows, they would know a great deal better how to appreciate the Diamond plow than they do. After I got to plowing with the Diamond plow, it appeared to be no labor for myself or team, and at night I would have three times as much ground broken up as I would have with the mold-board and twice as much with the Kerry. It seemed to me that breaking with the shovel was no breaking at all. I know how to appreciate such a plow as the Diamond plow. I plowed many a day with them, and plowed a great many days after I was 105 years old. It seemed a new thing to me every day. I loved to see the dirt whirl over.

Well I must get back to my boyhood again. There was nothing to cut grain with but the reap hook. It was a nice way to save grain, but you would consider it as being a very slow way to save grain, especially if there was a reaper cutting on one side of a field and you on the other with a reap hook. Well, it would look like doing nothing, and it would be getting nothing hardly done in a day. A good day’s work with the reap hook was one-half acre, and a man could not lay around in the shade long if he cut that much. You may ask the question how did you cut your hay? We, at that time did not know what hay was. I never saw a hay stack until after I was 35 years old. There was no such thing as hay. There was plenty of nice prairie grass growing all over the country and plenty of timothy, but people did not know how to make hay out of it, and if they had they had nothing better then than the reap hook to cut it with, and that would have been a slow business. I remember well the first scythe and cradle that I ever saw. There was great rejoicing among some of the farmers, and others said they they didn’t like them at all. These said they they wasted too much grain, but it was not long until all who were able to buy one used them. They were such an improvement on the reap hook that it soon went out of use.

Soon afterward, the mowing blade came into use. Then the farmers began to cut grass for hay. They first began to cut prairie grass, and afterward timothy and clover. Although this was a fast way to make feed, the people preferred fodder and the tops of corn. We always went over our corn and pulled the fodder and the tops off. It made good “roughness”, as we called it, and I would rather have it, yet, than hay.

I have told how we put in our grain. I will now tell you how we threshed it; we first went into the woods, and procured a lot of white oak, or hickory poles, about eight feet long; three feet from the largest end of each pole, we took an ax and beat the pole until it was limber. Then our flail was complete . We then took three, or four bundles of grain and laid them down, and beat them with our flails. We would repeat this process until it was time to ‘clean up’ our days work.. We did this by two men taking a sheet, and holding it horizontally between them, and making a fan-like motion of it to produce a current of air; another man would stand upon a box, or bench, and pour the grain upon it. By going over it three times, this way, we would get it tolerably clean. I have helped to thresh and ‘clean up’ many a crop of grain in this way.

You may think that we had hard work with such tools. It was slow work, but in those times I enjoyed life better, and made a living easier, than I ever have since. We did not run to the store for every little thing that we needed. One good reason for this was, that there was no such thing as a store or store goods in the country to run to. During many of my boyhood years the people never spent five cents for anything to eat or wear the whole year round, for we had no need of them. We made or raised our provisions. We made sugar out of the water from sugar or maple trees. If we run out before the time to make again, we did very well without it, for we nearly always had plenty of honey all the year round. Bee trees seemed to be inexhaustible. We often cut them down when making rails; sometimes as many as three or four a day. They were so numerous that often a tree was left standing when bees were found in it. If we went out hunting for them, and found one that was large or in an inconvenient place for cutting, we would leave it and hunt for another, in order to save time and labor.

There was no end to wild game. We often saw twenty or thirty deer, in one drove, feeding along the valleys. All we would have to do to secure one for venison was to creep along, through the wild grass, until we came close enough to them to pick one out, and then shoot it. The remainder of them would make the brush pop in getting out of the way.

There hardly ever was a time when I was growing up when there was no venison or bear meat in the house. Wild turkeys were so plentiful that we could kill one at almost any time we wanted to. We scarcely ever killed them except in the time of the year when they were fat. As for squirrels and rabbits they were not considered to be worth a load of powder and shot. The streams were full of fish. We had them to eat at almost any time we wanted them. We could catch them nearly as fast as we could bait our hooks and throw them into the stream. Wild meat was not much trouble to get. I have seen, I believe, as many as one hundred wild turkeys in a gang.

We raised our “bread stuff” and made our salt. There were many salt kilns. We would take our kettles to them and make it ourselves, or trade furs for it. As for coffee, there was none used when I was raised up. So you see, in this line, which consisted of what we eat, we had no need of spending one cent of money from one year to the next, and the way they lived then suited me much better than the way they live now.

We never thought of buying clothing then. We raised flax, hemp and cotton. And these were the materials from which we made our clothes. This gave the girls something to do, instead of being raised up in idleness, as a great number of them are today, without even knowing how to cut out and make their own dresses. They first prepared the hemp and flax by hackling it; next by spinning it; and, third, by putting it in the loom and weaving it. Then they did not run off to the dressmaker with the cloth, as they do now, but went to work and cut it out and made it. It was always the latest style, and it must have been the best for it was all the fashion with the women for about forty-five years since I can remember. I don’t know how log it was the fashion before I can remember. They were simply home made clothes, cotton chain, and hemp, or flax filling, and cut plain, without ruffles or flounces, or anything of that sort, I have often thought that if a woman had come into a crowd of the women of that day, and had frisked along with her hoop-skirts, dressed in silk, with her ribbons, laces, ruffles, and flounces, and with a hat stuck on the top of her head, and with her high-heeled shoes, breast-pin, bracelets, a great big hump on her back, a coat of paint on her face, and her hair bushed down over her forehead, the people would hardly have known whether she was a human being, or some sort of an artificial thing which some man had invented and put on stilts to try to draw the attention of the people.

Well, I am glad that I lived a good portion of my life out before such foolish pride came into the world, but I am sorry for any poor man who is simple enough to buy such foolish and simple things, which cost so much money, for his family, and which are of no profit. “The pride of the eye is not of the Father”. They had good reasons for not wearing such things then. One was because they did not have the money to buy them with, and another was because there was no such things in the country to be bought. Men, women, and children all wore the same kind of goods, and when they went to preaching then, it was not simply to show their fine clothing, as I believe is often done now. You may think it strange that we all wore the same kind of cloth, but it was all the fashionable suits we had in my boyhood days, and until several years after I was married. Well do I remember my wedding suit. It was all made of the same material, except my pants, which was made of flax altogether. My huntingshirt, which was worn then instead of a coat, was made of cotton chain and flax filling and my shirt of the same material. As for vests there were none then. Men wore huntingshirsts made of buck-skins, hemp, or flax. My wife’s wedding dress was the finest that the country afforded. It was homemade, cotton chain and flax filling, with copperas stripes running through it. In those days, cloth was part cotton was used more for ‘Sunday clothes’, as we called them.

It took a great deal more work to prepare cotton for the loom than it did flax or hemp or tow, for when our cotton was raised and gathered it seemed that the work was just begun. It was such a task to pick the seed out with our fingers, as there was no cotton gins at that time. So after the cotton was picked from the stalk, we had to pick the seed out, and then card it with hand-cards; after this was done, it was ready for spinning, doubled and twisted, reeled, and then it was ready for the loom. You see that it took a great deal of work to make cloth out of it.

Almost every family would have a cotton picking and ask men and women to come and help them. When a number had gathered in to the picking, we would divide the cotton into two piles, and then some two would ‘throw up’ pr ‘choose up’ for choice of piles, and then we would go to work in earnest. Some times they would get up a great excitement in the race, and then cotton seed would ‘fly’. There would always be some one, the next day after the cotton picking commenced who would ask them to help him pick, and thus we would continue until every family in the neighborhood had had a cotton-picking. So you see that we enjoyed ourselves and got our cotton picked also.

When cotton picking was over, the women went to spinning and the men commenced hunting and fishing, cutting bee trees, trapping, etc. O, we enjoyed ourselves.

As for money, you see that we did not need to spend one cent, and it was well for us that we did not, for there was hardly any money in the country. The first piece of store goods that I ever saw, was after I was married. I remember well what an excitement there was over it. It was a piece of calico. You may think it strange but people came for miles to se it. Right there pride and expense began, which have run along together ever since. The women began to cry out at once for new calico dresses. A few of the wealthiest farmers sent off for calico for their wives and girls to make dresses for to wear around in company. When they put them on they would flirt around and were prouder than they would be now of silk and satin dresses. This is the first time I ever saw a difference made by the people on the account of dress. Those that could afford calico dresses appeared to be stuck up, and shun the girls that had to wear their homemade clothes. This put the spirit of pride in the farmers, they all endeavored to raise money enough to buy their women calico dresses, and it took the most of the money out of the country. It also throwed the most of the stock in the hands of those who happened to have a little money at the time.

You could buy a good cow and calf for six dollars, and other stock was very low. So the people strutted around, and in a year or so the women all got their calico dresses. They took the best care of them, and one calico dress would do them a long time, for they wore them as long as they would stick together. The women were dressed too fine for the men with their hunting shirts and hemp and flax pants. But it was not long before the store clothes, as they were called, came into the country, and there was fully as much excitement over these goods as there was over the calico. The men soon got too proud to wear homemade clothes as well as the women. The pride of the people brought on them hard times, and in fact nearly went with many of the farmers who were trying to keep up with the pride and fashion of the country. But the pride of the people had just commenced.

At that time there were no fine parlors to furnish for the girls, no fine cushioned chairs. There was no pianos or organs for the girls to play on, and they were just as much concerned about making a living as the men. In my boyhood, a house with more than one room was a rare thing. They were made out of round logs, and in it we cooked, eat and sleep. It answered for a sitting room and parlor.

There was no such thing as stoves in the country. I never saw a stove of any kind until I was fifty years old. We had a wide fire place and a wooden chimney. The fire place would often take in a stick seven and eight feet long. The family had plenty of room at one end while the cooking was done at the other end. This would look like crowded living now. Well it was a little crowded, but we made out very well; but we could not have made out at all if it had taken as much furniture then for the people as it does now. As it was we done very well. Two homemade bed steads and a couple of trundle beds, which we shoved under the large beds in the day time, and a table, a few chairs and a shelf for our dishes, and our house had all the furniture in it we needed. Thus you see the cost of furnishing a house to what it now is.

I expect the young folks would like to know how the young people enjoyed themselves in those days. We enjoyed ourselves the best kind. But had we been as bashful and as shy about talking before the old folks as they are now, I don’t know how they would have got along. When it came to sparking there was no other show only to pick up courage and take your chair and sit up to the girls and go to talking to her before the old folks. It appeared that the girls used the corner next to the chimney when they boys were around. There was always a place left for them next to where the girl set, and after the young man came in he would take a seat among the family, and after he had talked to the old folks a while, and they appeared to be in a good humor and were friendly disposed, and the girl looked tolerably pleasing, and everything appeared to be all right, he would pick up his chair and walk around and sit up to her go to talking to her. After while the old folks would get sleepy and go to bed, and then was your time to talk of courtship, love and marriage. If the old folks got to sleep, and they generally did, we often stayed till the chickens crowed for midnight. Time passed fast on such occasions as that.

Of this part of my life I shall not give a full history I will tell you what a fix some of us young folks got into once. Five of us boys got our girls to go over the river to hunt strawberries. In crossing on our way there, we crossed on a shoal, and by stepping from one rock to another, we could cross without getting our feet wet, as the river was very low, and it was about one hundred and fifty yards wide where we crossed. We crossed the river and went out on the prairie, and roamed about gathering strawberries until the sun eas one half hour high, when we started for home. When we got to the river it was about waist deep and rising fast.. It had been raining up in the mountains for some time and was just getting down, as was often the case with that river. There we were all on the other side of the river and the sun down and five girls with us and no boat or canoe to cross in. We held a short consultation, and it was decided that each man should take his girl over. It was a big undertaking, but the best we could do. There were lots of wild animals in the woods, and it would have been dangerous to stay out all night. We stooped down and the girls got on our backs, throwing their arms around our necks, and we were soon crossing the river. I was the smallest man in the lot, and it chanced to be that my girl was very large , I expected she weighed one hundred seveny five or one hundred eighty pounds, and it appeared to me before I got across that she weighed three hundred. There was a tall fellow in the crowd, and it was decided that he was to take the lead; as it was dangerous if we varied either way up or down the river ten yards we would have got off the shoal and been in ten or twelve foot water. I got above the tall fellow, so if I started to wash down he would catch me. It was well I did, for when I got about half way across the river, my head began to swim, and I stumbled over a rock, and down I come, girl and all, and if the tall man had not caught us;, we would have washed over the shoal and drowned. I know by the way she held my neck that she would not have let go as long as she had breath. He raised me up and steadied me, and I made another start. By laying out all my strength and being particular as to how I set my feet down, I made it across. If ever I was glad to set safely landed over a river, it was that river. They all took a good laugh at my falling after we got across, but there was not much laughing until we landed. I was not the only tired man in the crowd. That has been about 97 years ago, and I remember it as well as if it had been but yesterday, and I don’t think I should forget it in 97 years more, if I should live that long. I never saw a side saddle until after I was twenty one years old. There was no wagons, hacks, buggies nor anything of that kind. When the women went to meeting or any place they had to ride behind their fathers, brothers or beaus.

One time the young folks got a good joke on me. I had been talking to a girl at preaching, and had agreed to take her home. I was a little slow, or her father was a little fast, one, for just as I got nearly up to the stiles she jumped up behind her father, I rode up and told her to get down and get up behind me, but her father rode off, and the people began to laugh at me. The boys laughed at me for a long time over it. I give these events merely to show how different everything was in my raising, one hundred years and over ago. We enjoyed life than a great deal more than they do now.

In those days the children had a poor chance to learn much. There were scarcely any schools in the country, and you may think it strange, but hardly any of the old folks could read or write, and they did not take any interest in the education of their children. The first and only things that they thought their children should learn was how to work on a farm and to fish, and to hunt. The boys and girls of today know more at the age of twelve than the men and women did then. The people were very ignorant in those days. If a man could read or write, they considered him well educated.

Until I was about twenty years old, I had never been more than twenty miles away from home. About that time I concluded that I would go with some drovers to New Orleans to drive some cattle. I saw many strange things that excited me. I would catch myself standing hollering at the cattle and looking at something else until the cattle were nearly fifty yards ahead of me, and several times the owner of the cattle had to call to me to come ahead. There were men going around selling sweet potatoes, fresh oysters and so on. Little boys with brooms crying chimney sweeping. For over one hundred yards there were sheds with meat and vegetables of all kinds hung up and setting around. This was all new to me and excited me considerably. We were six weeks on the road. They paid my expenses and gave me five dollars for the trip. That was more money than I had ever had at one time in my life. I started out in town to see what I could buy. The first thing that I saw I wanted was a lot of cheap jewelry. The man had a box of all sorts of finger rings, ear rings, breast pins and so on, representing them to be gold and worth ten times as much as he asked for them. He said he was bound to have some money to go to a certain place to prove up an estate where he would get a million dollars, and he did not stand on trifles in such a case, as he had to have money to go on. I believed all he said and went to buying, and in a few minutes he had my five dollars and I had a lot of cheap jewelry that was not worth fifty cents, and on he went to find some other greenhorn. I was green in them days, but I was not the only greenhorn.

I suppose you think strange of a great deal of my writings. When I look back 110 years and see how the people live it seems strange to me. There has been vast improvements. In my boyhood there was no wagons in the country, and there were lots of men and women that never saw one in their lives. I remember well the first wagon I ever saw. It was as big a sight to me then as the first rail road car was. I was about 15 years old when I saw the first wagon. An old Dutchman had gone off to buy one. I remember of hearing an awful lumbering a way up on a rocky hill not far from where we lived, and the whole family going out to the yard fence and standing and listening at it, and of someone asking what it was and father telling them that he expected it something to haul on that run on wheels that they called a wagon; that he had heard the old Dutchman had gone off to buy one. In a little while he came up riding one horse and leading the other, that was the way they drove then. He drove up and stopped and father asked him how he liked his wagon? “O very well, very well!” he said. “I had rather have it than two sleds, though it tries its best to run over my horses in going down hills.” You can hardly imagine the excitement that wagon caused. People went for miles to see it, and all I could hear for weeks was the Dutchman’s wagon and what loads he could pull on it. In the course of a year there were several in the country; though they came into use very slow. Not many farmers could raise fifty dollars, that being the price asked for one. Fifty dollars was as hard to get a hold of then as five hundred is now. There was but little money in the country then, and people used skins and furs in the place of it.

I remember the first fur hat I ever had. I gave ten dozen rabbit skins for it, and I have no doubt but those skins passed through fifty different hands before any money was paid on them. Once or twice during the year some one went through the county and bought up all the skins and furs of all kinds, and the people knew about what they were worth, so they were used as money. You could buy any knid of stock and pay for them or part of them in furs and rest in furs in six or twelve months from that time at whatever price they were going at. Furs were in a great demand, and there was considerable trapping done. Stock of all kinds was very low. A good horse was worth twenty-five or thirty dollars and a plug horse from six to twelve dollars, cows and calves seven to ten dollar, calves from seventy-five cents to a dollar and a half. Hogs were almost given away they were so plentiful.

People were not so particular then as now. They never thought of selling seed corn or potatoes or anything of the kind. If we had such things to spare at all, we had them to give away to our neighbors, and always felt good over it and thankful. It appeared to me that people enjoyed life then better than they do now and were not half so craving as they are now. If a man killed a fat hog or sheep or anything of the kind, he would send for his neighbors to come and get some, and did the same when they killed a bear or deer, and never thought of charging a neighbor for anything of this kind. I do not know what has brought about such a change in the people without it is pride. If the people had the necessaries of life then, they were contented. There was fully as much idle amusement than as now. Wrestling, fighting shooting matches, foot races and horse races. There was no sport I was fonder of then wrestling.

Although I only weighed 135 pounds after I was a grown man, in fact that is the most I ever weighed, there was but few men that could throw me down, in fact I never found any that could. If all the men and boys were standing in a row that I have thrown down it would surprise you to see them. I don’t know whether you could stand at one end and see to he other or not. I never gambled much on wrestling, but generally done it for fun and to show my skill. The last man that I throwed was Alec Leathers, after I was one hundred years old. We were working the roads and he began to boast about being such a wrestler. He was a stout looking young man. Some of the men told him that Uncle Bobby Gipson had seen the day he could throw him easy. He hooted at such talk. I told him I had never seen the time yet but what I could throw him if I was so amind. He put at me for a wrestle. I told him I did not want to throw him down, and he said the reason was because I could not. I stepped aside and told him to come on and I would show him I could. We took breeches holds, and I asked him if he was ready. He said yes and not much quicker said then done, for I knocked both of his feet from under him, and down he came. After they all quit hollowing and laughing, I asked him if he wanted to try it aain, and he said, ‘No’, that had had enough of the fun.

He lives now in the same neighborhood that I do,, and I never meet him but he has something to say about our wrestle. Well, I can say that I threw the last man that ever bantered me. I would have wrestled when I was over one hundred years old if I had been bantered. Fighting was another great amusement that was indulged in then. Men would fight at musters and on other public days for no other purpose than to see which was the best man. As soon as they would quit fighting they would ’make friends’ and that woud be the last of it. There hardly ever was a public gathering when I was a young man, until I was twenty-five or thirty years old, at which there was not from five to twenty-five fights; at night they would go away as good friends as ever, and would not think much more about than them there would be so many wrestles.

I believe that the hardest fight I remember of ever seeing was between one of my brothers and a man whose name was Kerby. Eight or ten of us were rollig logs. Both were considered the “bullies” of the country, as we called them who were the best fighters. We had quit rolling logs to get a drink of water, we saw Kerby and three other men leisurely walking toward us; one of them had a jug in his hand; they came to us and spoke very politely and friendly, and then passed the jug of whiskey around. Kerby then turned around and asked my brother, John, if he was the “:bully”:of the neighborhood. John told him that he was as far as he had been tried. Kerby told him that he could not have said that and told the truth, if he had ever tried him. John told him that he had not tried him, but if Kerby wanted to, it would not take long to try it. Kerby told him that he had not come to try, but he came to whip him, if he did not ’crawl under’ and not fight him. John told him that he would have to whip him, for he never ’crawled under’, nor ‘backed down’ unless he had to; so they chose their seconds. John chose me, and Kerby chose one of his crowd. They made a ring, and appeared to be as cool about it as they would have been if they intended to it as a meal of victuals.

They stripped themselves of all clothing except their underclothes, and stepped into the ring, and went to knocking. They knocked in good earnestness for a long time. It was “so good a man, and so good a boy,” as the saying was, John’s friends hollowing for him, and Kerby’s friends hollowing for him. After they had fought for quite a while, both were as bloody as they could be about their faces and from their waists up. I told those standing by to see that I showed no foul play as I reached over the ring and took a clot of blood out of John’s nostrils. This appeared to revive him very much, for his nose was so stopped that he could not breathe through it. I saw that Kerby was beginning to weaken, and some of his friends proposed that we part them, but I raised my handspike and told them that I would ’brain’ the first man that interfered, for they were fighting to decide which could whip, and that it had to be decided. They fought a while longer, and at last Kerby told them to take John off, that his wind was too long for him. Both were just about exhausted, and consequently it was not a hard job to separate them. John tried to jump up and hollow, but I don’t think he raised both feet off of the ground, and said that he was the best man.

They then passed the jug around, and went to the spring and washed, and dressed. The jug was passed around again and John and Kerby shook hands and parted as the best of friends. They went back, and we commenced rolling logs again. We had to give up one good hand, for John did not roll any more logs that day; but he had gained a great victory, as he was then the acknowledged “bully” of the neighborhood, and had no more fighting to do. I never took so much delight in fighting as some men did, but I have had several fights in my time. The most of them originated from wrestling. After I would throw men down, they would often say that I could not whip them, and I convinced every one of them that they were mistaken.

Once, at a muster, there was a tall fellow came along by our company and told the captain that he had the “scrun iest” company in the field and commenced laughing at us. The captain told him that the least man in his company could whip him. The fellow said that he would see him after the muster. I thought no more about it until after the muster was over, when I saw the captain and the large fellow coming into the store where I was sitting on a keg. The captain pointed at me and said, “Yonder he sits now,” and here he came in a run toward me. I jumped upon my feet just in time to dodge his lick, and I struck him at the bur of the ear and knocked him down. He had barely struck the floor before I was on him with both my thumbs in his eyes, and he hollowing, “Take him off.” He hollowed none too soon to save his eyes. He said that I whipped him before he had time to get mad. It was several days before he could see very much. I saw him several times after that, but he never took a “running shoot” at me again.

Until I was about forty years old, there was nothing in which I took greater delight than riding for horse races. I always thought when there was a horse race anywhere in the country that I ought to be one of the riders. I only weighed about one hundred and thirty-five pounds, so I was just about the right size. I rode for many races in my life time. I was not afraid to mount any horse and ’put’ him through the track although I have had many narrow escapes from being killed or crippled. When there was a race to be run it was generally followed by racing during the remainder of the day. As soon as one race was run another would e made up. Sometimes six or eight races would be made before the day of the race. Very often I rode ten or fifteen races in one day. I hardly ever bet, but I earned plenty of money riding races. I remember well the last race that I ever rode.

The morning of the race my wife was very much opposed to me going which was a very uncommon thing, for usually, if she was opposed to it, she would not say anything; but that morning she said, “Robert, I don’t want you to go to the race today, but if you will go, I don’t want you to ride for a race, for I never slept half of the time last night; every time that I would fall asleep I was dreaming about you riding races and every time I dreamed that you was thrown off and badly hurt; I was bothered about you all night. I said I did not believe in dreams, but I promised her that I would not ride a race that day. I did not think that I would, but I had not been on the ground but a little while until a man came to me and wanted me to ride a race for him, and said that he would give me one dollar to ride and five dollars if I beat; but he said, The mare is somewhat hard to manage, but if you can keep her in the track, she will be sure to beat. I told him that I had thought of not riding that day, but I would ride for him; so I soon had the mare in charge. I led her up and down the track once or twice and jumped upon her.

When the word was given to go, I started her and gave her a lick; it seemed to me that she almost flew; I looked around and saw that she was leaving the other animal for behind. Just then several who bet on her began to hollow and throw up their hats. That scared her, and in spite of me she flew the track. She ran through the woods with me, and it seemed that I could pull just hard enough on the reins to held her steady. She ran about a quarter of a mile with me and came to a stake and ridered fence and ran along the side of it. I expected every time I passed a stake that my head would strike it, so I dropped the reins and grabbed a stake. I think it threw me five or six feet above the fence, and I fell upon the next panel of fence. When I became conscious there was a crowd of men standing around me, and some of them working with me. I was bruised very bad, but I soon recovered. That was the last horse race that I ever rode. I have believed in dreams ever since.

You may think that we had no law, as I have said nothing about it, and have said so much about fighting. If men wanted to fight to decide which was the best man, they went at it and the best man whipped and that was all there was of it, but if a man was mad at another and beat him, and the other did not want to fight, the one who beat the other could have been arrested and tried by a jury, as such would be now. The fine, if it was money, went to the man who was not in fault, after all expenses were paid. You seldom heard of one man suing another for fighting, for if he did he was looked on as being a coward. We had laws and severe penalties for violating them than we do now. If a man used a knife, rock, stick or anything else on a man unlawfully, he was whipped at a whipping post or branded A.C. for a coward, the brand being held on until he said God bless the stare three times in succession for stealing, all amounts of five dollars and over, he was branded with the A.C., for a coward, and had to pay back the amount to the man he stole it from in six months from the time of trial, or he was branded again, and so on every six months until all was paid back with interest. For less than five dollars he was whipped at the whipping post with from ten to thirty-nine lashed on his bare back.

There was not much stealing in those days, and as for murder in the first degree as a man was often taken up, tried and hung in less than a week after the deed had been committed. They did not fool around with a murderer and make it cost the state a thousand dollars or more, but made short work of him. There was not near so much meanness done then as now.

I have run several narrow risks of being killed in my time. I was throwed from a horse when I was 106 years old. I had been at Smith Gipson’s one of my sons, on a visit and had started home, and had a little creek to cross; but there was no water where I had crossed. There was a bending tree standing on the bank of the creek, and I was riding in a trot and my head struck the tree and threw me off backwards and knocked me lifeless for a good while. I was found and taken back to the house more dead than alive.

I lay in bed almost six weeks, and was fed all I ate during that time with a spoon; nearly all who saw me thought I would die. It did not kill me, but it broke me of horseback riding, and I have not done much riding by myself since. I believe had it not been for that fall I would have been spryer now than I am; though I have no room to complain, for I suspect I get around as well as any man in the United States, who is one hundred and eighteen years old.

After I was one hundred and three, I was thrown from a wagon and three of ribs broken. Although I had so many narrow risks I never had any bones broken, till then. In that respect I was very lucky. From my boyhood up till the present time I never was any hand to keep trouble, but when it came to me I always threw it off as quickly as possible. The most trouble I ever had was my first wife’s death: she has been dead about forty-five years; and I can say I don’t believe there is a more loving, faithful and devoted woman living than she was. It was hard for me to give her up, but I now see she has a home in heaven to which I am hastening, and that I shall see her again, and know her; for the Bible says “ye shall knew as ye are known.” She died a Christian woman without an enemy on earth. “Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord, for henceforth there is laid up for them a crown of righteousness.” I often think of the happy times we had here on earth; many words she spoke are still fresh in my memory. I often remember her telling me one day to buy some apple trees and put out an orchard. This was over fifty years ago. I told her that I was getting too old, that I would not live to eat the fruit. Sje said as for her part she was in no hurry about dying; yet, poor woman, she would not have lived to have eaten the fruit, but I could have put out several orchards and eaten of their fruit by this time.

I was about seventy yearas old when my first wife died, and it was but a short time before one of our children died, a girl sixteen years old, and while she lay sick our youngest child, H.C. Gipson fell into the fire and burned himself very badly so as to make a cripple out of him self for life. For over six weeks we had to work with him day and night to save his life. All those misfortunes happening so close together, made it the unhappy part of my life. This left me a little girl to keep house; one little crippled boy and three other boys all small: this looked like I was left in a very bad fix, but I went ahead and did the best I could, which was poor enough, I can assure you. My little girl soon grew uo until she kept every thing done up well. About the time I began to think I was fixed to keep house once again, my girl married and again I was left in a bad fix. Four boys and no girl! I soon got tired of keeping house and farming too, so i concluded to go out and hunt me up another house-keeper.

The first I married was for love, the second time was for convenience and a housekeeper, I went to see some old maids; some were used up, some I wanted but could not get, and others I could get but did not want. At last, I went to see a widow with four children. I had four, and I began to think I had found the right one. I suppose she did too, we soon made a match. I established her in my house, and everything seemed to go on all right for awhile, but it did not last long. The children began to fuss; I did all I could to prevent it, still they did not get on well at all. This bothered my wife and her eldest son left home; two others died leaving her but one little boy. One day she surprised me by telling me that if I had just as soon, she would go and live with her children.

“Why Mother,” I said, “What is the matter? Have I not always treated you well?” She replied “Yes Daddy, you have always treated me well, but if you would just as soon, I will go and stay with my children.” I told her I did not wish her to go, but I also did not wish her to stay against her will. “Well, she said she had rather go. “All right,” I said, “One day next week I’ll take you where you want to go.” That was on Saturday, and on the next Thursday, I yoked up the oxen and loaded her things on the wagon, and the boys and myself took her stock and drove her back to one of her children. They were surprised when they saw us coming, but we soon made them understand what was up.

We went in and staid all night, and the next morning I asked her if she had any objection to my getting a divorce. She said she had not. I had always treated her well and never given her a sharp word, so I shook hands with her and we parted good friends. I saw her afterwards many times, and was always glad to see her. There was no sport as favorite as shooting. There was scarcely a week passed, in pretty weather but what there were one and sometimes two shooting matches in the neighborhood. They first shot for a beef, and when the prize was won, then the shooting appeared to have just commenced. They had pony purses as they called them; every one who wanted to shoot would put in ten cents, and the best marksman carried off the pile.

There was a man around there by the name of Smith who was given up to be the best shot in the county. He would bet one dollar and a half that he could hit a spot as big as a ten cent piece, ten steps off, shooting off hand. One day he got so drunk, along in the evening that he could hardly walk. He staggered around and finally made a spot and made the usual bet. It was instantly taken up he being so drunk, and he got up with his gun: he could scarcely stand, but he tried to get sight awhile, and could not. At last he asked for some one to steady him, so some old man did and he blazed away and knocked the centre out. After that he wabbled around and made another spot, but he could not get a bet. Some said he was so drunk that he would knock the centre out every shot.

Once there were two brothers at one of these shooting matches and one of them got his gun choked. They went to a blacksmith shop near by and took the stock off the gun. One of them put the barrel in the furnace and told the other to blow the bellows; he looked in the gun barrel to see if the lead was melting and the gun went off and blew the whole top of his head off.. The other one came running back and said that he wanted some body to come down to the shop quick that the gun had gone off and killed his brother, Some of them went down and sure enough, there he lay, dead. They took him home, but that did not break up the match. They shot on all day and at night they shot to see who should have the lead. All hands shot thirty yards and the closest shot took all the lead which had been shot in the target all day; this was after night; by a pine torch light. I could tell of many accidents and narrow escapes at these matches but they would not be interesting.

When I remember the many narrow escapes from being killed I do, myself, wonder that I am still alive at this writing, and able to walk around in my son's yard where I am now living: and can get up and down the door steps. Still I am alive and of course I have had a strong constitution, but I believe the way I have taken care of myself and my manner of living has had a great deal to do with my living so long. I found out one hundred years ago, when I was a boy, when I happened to miss a meal, and then over-loaded my stomach, that I felt very dull and stupid for some time afterward; and if it was supper I would not rest well during the night. I saw that it was hurting me and I stopped it, and no difference how hungry I got, I found out the quantity of food I felt better over and I ate that and no more.

I often got up from the table before I was satisfied, and I did very well till the next meal. I never was a very hearty eater, and breakfast was my heartiest meal. I have always eaten three meals a day when I could get them. Going so long without meals and getting so hungry and then cramming a lot if ill-chewed food into the stomach, will, I think do very well for one day, but it will soon get a man's stomach out of fix and he will die if he keeps it up long. All the supper I have eaten for years has been a biscuit and a cup of milk; or some cornbread with my milk. One glass of milk is all I have ever allowed myself to be in a hurry in eating, but taken my time, and a man ought to. I would advise all, young and old to eat slowly, chew your food well, and never, under any circumstance, ober-load your stomach with more food then it can easily digest; you will feel better and enjoy life more, and i believe, add many days tp your lives. "Be temperate in all things,: is the word of our all-wise creator, and this is a command given to man, that if he violates he will suffer to a greater or less extent; nor is this all: every command of God that man does violate he suffers for. If we keep his commandments we dwell in him and he dwells in us, and if he is in us he is there to comfort and protect us, and he is able to make us to rejoice in infirmities just as he did old Paul. Being one hundred and eighteen years old, I can see but very little, and am infirm in many other ways, but yet all is well with me for god is with me, and is helping me here on earth; I am just waiting his own good time when he will take me to heaven. o blessed thought! for me to think I am fast hastening to that blessed place; although I do not crave death, but want to live as long as the Lord want me to. I want ever the Lord's will to be mine.

I have always been as particular as possible to keep my feet dry. This, too, I learned by experience. In my younger days I have often went for a half a day at a time with my feet wet or damp, and it always made me feel drowsy and dull. As soon as I found this out I just put a stop to having them wet. If my shoes leaked I went and had them mended. If a man will find out what makes him feel bad and stop it, there is no need of him going around with a cane in each hand at the age of eighty, but instead of that he should be able to do good work at that age, I could hardly tell I was failing at that age. I never got so busy in work as to work in the rain, but always tried to leave the field in time to get under shelter before the rain began to fall. People often laughd at me for unhitching my team and going in the house and sitting there an hou or so until it cleared up. But that was simply my mistake, and I had rather have been mistaken once than to have got soaking wet once, for I found getting wet made me feel bad and I never liked to do anything that made me feel bad when I could help it.

. I never would work out in snow storms, but I have always found more comfort in sitting in the house and looking out at it snow than to be out in it. I never was in a hurry to get out of the house to work of a cold frosty morning nor in heavy dews, and when I got cold and could possibly get to a fire, and if it was very cold I did not leave it soon. I took good care of myself in cold bad times and in warm dry days I could work and it did not hurt me, for I was well and not moping around with rheumatism, headache, and sore throat and so hoarse I could not answer my wife when she called me to dinner. In the spring when I commenced plowing, I got up about daylight, fed and curried my horses and come back to the house and at half past eleven I turned out for dinner. This gave me time to rest. At two o'clock I started back to work and worked until time to turn out, feed, water and eat supper about one and a half hours before sundown. I worked in this way as regular as I eat my meals, but when I got tired I set down and rested, no odds how busy I was as it hurt me to work when I am tired.

Many a man has lost his health by over work, when one half hour's rest would have put him, all right; just the same as a horse under such circumstances. You may work a horse until he is very tired, and then rush him on and he is often killed, or his constitution broke and hi is never good for anything afterwards. This is noticed in horses more than men. A man can soon tell when he has got the best of his horse, but we will overwork, expose and kill himself by inches and never appear to find it out until he can not do even one hour's work, and then he will begin to say that old age is telling on him, when perhaps he is not over 45 or 50 years old. He is mistaken.. It is not old age, but a broken down and abused constitution, when the ought to be in the prime of life.

Be temperate in all things. The age alloted to man is 110 years, and if he would not violate the Word of God and be temperate in all things and take care of himself, there is no reason I can see why he shoud not live out his days. I never had but one spell of fever, and that was when I was 43 or 44 years old and I went into the barrcks to see the soldiers that were quartered there, and took the fever. I lay five weeks with it, and finally wore it out. I never took a dose of medicine either. I believe that there are more people die from the effects of strong medicine than there are cured by it.

I have taken but very little medicine, and have lived a long time. I have used coffee ever since it has been in general use in the United states. Until I was 25 years old there was scarcely any coffee used. There were plenty of men and women who never saw any, and would have been like one of our neighbors after ti began to get scattered over the country: there were several of us talking about coffee being used, and he said he did not think it was much account. He had never bought but one pound of coffee and then his wife did not know how to cook it. She had boiled it a whole halfday and then could not get it tender. I have used it regular since I was 35 or 40 years old. One cup a day is about the way I have used it. I learned to drink it but never learned to like it. I preferred milk, and always used it in preference.

I have used tobacco ever since I was sixty-five or seventy years old, and never had taken but one chew before in my life until that time, and it made me so sick that I did not think that I ever would try it again, but did. I had a habit of chewing sticks, and when I was riding around , chew my riding switch. Ond day a preacher and I by the name of Wright were going to a class meeting, and he said, "Brother Gipson if you would go to using tobacco you would stop chewing up you riding switch and sticks. It is a wonder you don't get splinters in your throat." I told I had taken a chew when I was a boy and it like to have killed me. He said I did not commence right. He took his tobacco out and told me to take a small piece in my mouth for a short time, and after while put some more in and let it stay a little longer, and it would not make me sick. I did so and it was but a short time till I had such n appetite for it that I could not do without it, and have used it ever since. I never smoked.

I have tried several times to quit it, but have not succeeded. It is a nasty, filthy habit, and I have never heard a man say yet who has an appetite for it, but what he regretted he ever commenced the use of it. It is likely that if I had used it from my boyhood I would not now be living. Boys and girls, take an old man's advice, who is 118 years old, and perhaps the oldest in the world and you will never regret it. It will do you no good and perhaps a great deal of harm. Some perhaps will say does the old man love his dram? He does.

In my bringing up distilleries were as thick and plentiful as mills are now, and there was scarcely any one but what kept whiskey in the house and used it all the time, both men and women used it. It was very cheap and all could get it. To take a sack of corn to the distillery and get some whiskey, was just as common as it was to take a sack of corn to mill and get meal for bread. Whiskey was pure in those days, and it did not injure one as it does now, and you hardly ever saw a man drunk. Whiskey was taken to the field the same as water. It was worth fiteen and twenty cents a gallon, and we drank it whenever we felt like it.

When the distilleries were stopped by being a per cent put on every gallon, and men had to pay a license for handling it, this stopped all the small distilleries, and whiskey went up to seventy five cents and dollar per gallon. This and the poison that was put in it stopped its use to a great extent. I kept it by the barrel and sold it, and the profit I made on it kept me in whiskey. I soon found that it was not pure and quit keeping it in the house, but still used it occasionally, but I did not use it steady. I still take a dram occasionally. If I used it steady the poison in it would soon kill me. If you want to live out the days allotted to you, do not drink too much whiskey.

I have been a man fond of fun, and now see how silly I have acted a great many times. It might be interesting to one to hear of some of these silly adventures, though I think so little of them that I do not care about relating them now. I had a little fun once after I was a married man that caused me to have a hard fight. There was a widow woman living in the neighborhood, and there was a married man fell in love with her, or at least the man's wife thought he had.

One evening about dusk her and four other women came up to my yard gate and called to my wife to come and go along and see a fight. This injured woman whose husband was said to be in love with the widow, was going to give the widow a good whipping, and wanted my wife to go along and see it well done. She told she could not go and tried to persuade them not to go. I urged the women all I could to go ahead. I told them I would slip my wife's dress on over my clothes and go along if they would promise not to tell any one, not even their husbands. They all promised they would not.

My wife said it was none of my business and it would be likely to get me into trouble, and if she was me she would not go. I was not to be bluffed off so easy as that. I told my wife there was no possible chance for it to be found out and there would be no harm in going, and that I would not say a word nor do anything but look on. She at last gave her consent, though I knew it was against her will. She got me one of her dresses and I put it on and it was so long for me I could hardly walk without holding it up. as it was very low and she was a tall woman. I put on the bonnet next and was ready to march to the battle. I felt as though I was out of my place; but then I was determined to see the fight.

I did not think that I would be recognized, for the dress I had on was like all the rest of their dresses, made out of home-made flax and cotton with strips running through it. The women in those days were all dressed in uniform. A man could not tell his wife by the dress she wore. We soon arrived at the battle ground, as it was but one and a half miles from where i lived. The widow was at home, and the woman that was going to whip her called her, and she came o the door, then she told her that she had come to whip her; but that she should have a fair fight, and those that were with her would tell her the same, as they had come along just to see the fight, and would not touch either until one or the other whipped and then only part them. They all told her that they did not come to take sides but me, and it was unexpected to me, and awkward, for I knew if I spoke she would know my voice. i said nothing but thought a great deal.

As soon as we got there the widow had told her little boy to step out the door and run and tell her brother to come quick. He was a great big fellow, and lived about a quarter of a mile off. The woman kep telling her to come on, and the widow told her yes, as soon as she finished washing her dishes. They kept parleying along in this way for some time.

Finally I heard the cornstalks breaking around at the corner of the house, and I looked around and here came her big brother, and I and the women all started in a run, and him after us. I had to hold up my dress as I run, and my legs got tangled up and down I came. I was looking every moment to get a lick on my head with the club, but I think he was just trying to scare us, for when I fell he stopped and went back. I jumped up and never looked back until I got nearly home.

That was about the hardest foot race I ever run. I never knew women could run until then. After we got to my house and rested up and told of our adventure it was laughable, but there was none of the crowd that felt much like laughing but my wife, and she had a good laugh by her self. You know how hard a good joke is to keep, and it was not long until some way it leaked out, and the widow's brother sent me word that he heard that I was in the mob that had come to whip his sister, and as I had not succeeded, and as I was so keen for a fight, he would give me a chance to fight a man.

He was a great big fellow, and I weiged only one hundred and twenty pounds so you may know I dreaded him. He ws considered a dangerous man by all the neighbors, and I sent him back as smooth an answer as I could, and told him that I had no idea of taking a hand in the fight; but that the women had come by, and I seen that they were determined to go ahead, and I thought they might even kill his sister, and instead of wanting to whip her I went along to keep them from hurting her, and that he was judging me wrong. I had nothing against his sister nor him either.

I was sorry that he had mistook me for an enemy while I was trying to save his sister from the hands of the women, proved they tried to injure her; that I intended that none but the two should take part in the fight, and if either hurt the other too bad, that I was going to part them. I thought that this would satisfy him, but it did not. The next time I saw him was at a reaping in the neighborhood, and him and I were both at it. This was the first time that we had been together since the occurrence. He was binding and shocking, and I was cutting with the reap-hook. At noon he sat on one side of the table and I on the other, facing each other. He looked at me and smiled, and asked me how I felt. "O very well, how are you?" I said. "Very well," he said. "I want you to eat a big dinner, for I am going to whip you after dinner." I told him that I guess he was mistaken. He said I would see by waiting. I told him of course I would, and that was all that was said. I kept my eye on him, for I knew that I would have him to fight before we left the reaping or back down, and I did not intend to do that.

After we had eat and started to the field, he was ten or fifteen steps before me, on a nice place at the side of a straw pen which had been cleaned off to frail out wheat on and he stopped, and I knew the time had come to fight or run, or to make him cry enough or him to make me cry enough. I had my doubts as to which would whip. I walked up, and he said "Gipson, here is as good a place as I can find to whip you on, and I can do it on less ground than it will take to put you away in." I told him that it was not decided yet, but I did not want to fight him. He said I need not fight, but that he was going to give me a whipping. He came at me and I knocked his lick off with my left hand, and let him have it at the bur of the ear, and down he came, and I jumped my full weight on him with my boot heels before he had time to raise up on his feet, and just before he got straightened up, I let him have another blow, and knocked him down again, and jumped on him and began to pound him. He finally got my finger in his mouth, but just at that time I got both thumbs in his eyes, and let go of my finger to cry enough. He hollowed it out in a hurry. They pulled me off of him. He was badly banged up, while I was not hurt but little. My finger was bit so as to make it sore for a while, but I tied it up and went on reaping. He had all he could stand without doing any more work that day. Some of the men got to running him about me whipping him. He said that little bow-legged scamp was so small he missed him every time he struck at him. A fight settled everything in those days, and we shook hands and parted as friends.from that time on. It was the last time I ever dressed up in my wife;s clothes and started to see another woman fight. The neighbors never got done laughing at me about running and falling down and the women getting ahead of me, and so on as long as I lived in North carolina.