Dateline:October 24, 2021

The Third Man

Comments on the Third Man?

Senator Kefauver investigated organized crime, the Schuman Declaration laid the keel of the European Union, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel opened, North America was circumnavigated for the first time, President Truman sent U. S. soldiers into Korea, and the lyricless theme song of a movie, “The Third Man,” became the most popular song in America.

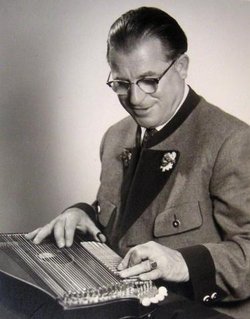

After a day of filming in Vienna, director Carol Reed, with actors Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, and Baroness Alida Valli, heard zither musician Anton Karas playing in a local bistro. They took Karas to Britain, provided him a translation of the script (he spoke no English), and commissioned him to compose a score for the film. The theme song was released as “Harry Lime’s Theme” in Britain, and later as “The Third Man Theme” in America. It was Billboard’s number one hit from April 29, to July 8, 1950. People who devoured Churchill’s many books; people who pumped gas, taught school, and milked cows, all loved it.

During the second half of the 1940s, America transitioned from war, to peace, back to war in Korea. The cold war emerged, the depression years, though forever in mind, receded in fact, and harbingers of a new order tickled the popular imagination. The movie that strobes the moment in iconic stop-fame is “The Third Man.”

It was a timely drama of politics and morality set in post-war Vienna. The plot involves international confusion, post-war racketeering, and the sort of indeterminate angst that typified the intellectual ferment of the 1950s. Its drama boils down to the good-guy/bad-guy, damsel-in-peril elements common in popular cinema. Welles is the happy rogue who fakes his own death, remaining off-stage for much of the movie. Cotten is the vaguely clueless good guy, blundering innocently after the truth. Valli is the Pauline of Perils making the best of disaster. Her arrest, and impending deportation to the Russian sector, are the mid-century equivalent of being tied to the railroad tracks by Oil-Can Harry (Lime). The whole thing is filmed in that shadowy, dark-street, odd-angled shtick that TV turned into cliché by the 1970s.

The movie has ascended into the pantheon of classics, endlessly analyzed and critiqued, its ambiguities eternal obstacles to moral simplification. Everyone can agree that Harry Lime’s (Orson Welles) crime of stealing, diluting and reselling the meager supplies of penicillin was horrible. Everyone can agree that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) is a bungling, naïve idealist, full of the sort of good intentions paving the road to Hell. Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli) is just a struggling victim, caught in the pincers of corrupting power. Still, doesn’t everyone agree Lime is a charming rogue? Isn’t Martins fundamentally good? Is Schmidt’s attempt to control her destiny just foolishness? What prompts her to be so loyal to Lime? Was Lime’s final nod to Martins, inviting Martins to shoot him, atonement for his sins, or just an easy way out? The 1950s were just beginning, but this movie is now seen as a good summary of its psychological signature.

For many people, the music makes the movie. The haunting strains of Karas’ zither hide slyly in the background of the shadowed faces and cobblestones, to come swelling out in evocative melodies and rattling chords at peak tension. In the original movie, and in the good copies still available today, the music carries the emotional impact, like a breeze carries a memory-fetching bouquet. Unfortunately, over-engineered attempts to restore and preserve the movie have rendered some of the copies incoherent. PBS, for example, sometimes airs a deplorable cut, the music too loud, strident, and discordant, its tone ringing like an alarm clock.

...

The movie's merits have been steadily appreciated in the seven decades since 1950, but it's the music we're considering here.

My grandmother would ask to have it put on the record player, and I would be elated. The song was a force of nature, and we both loved it.

At that moment in 1950, midway through the twentieth century, with the adults imagining a tranquil second half, and the children straining to imagine beyond lunchtime, Anton Karas' zither spoke to everyone.

Its voice, a jangly, wandering melody, forever renewing, organized by that swing-gait rhythm always swelling, shattering and keeping on, spoke to young and old with a message hopeful, clear eyed, sober, compelling and gay. Just the thing for a summer day at the inflection point between Atomic destruction, and accelerating change, an inflection point still beneath our feet.

...

Who in the world cares about zithers?