Comments on New Mexico?

August 20,2025

Since we published this page in 2020, its thesis has become the agreed narrative: the Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894 was manufactured in a 2004 publication of the Foundation of Economic Education. The Attic of Gallimaufry (this page) is often cited as a debunking source. Alas, the matter still conjures historical nonsense.

We recently saw a post in The Times of London grappling with the non-existent 1894 manure quotes. It was headlined, “We were buried in fake news as long ago as 1894”. The fake news, of course, didn’t exist in 1894. It originated in 2004. Dr. Kurt Godel’s 1931 incompleteness theorem didn’t give us license to ignore logic.

By the way, plenty of people who should know better continue flogging the long-dead horse of the fictional crisis.

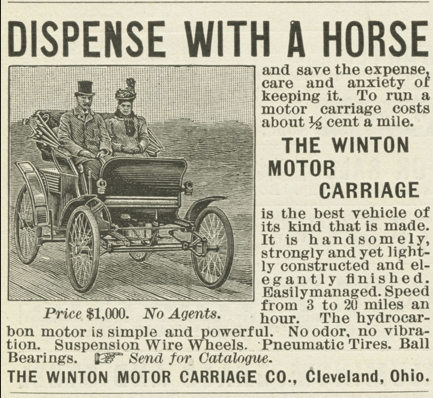

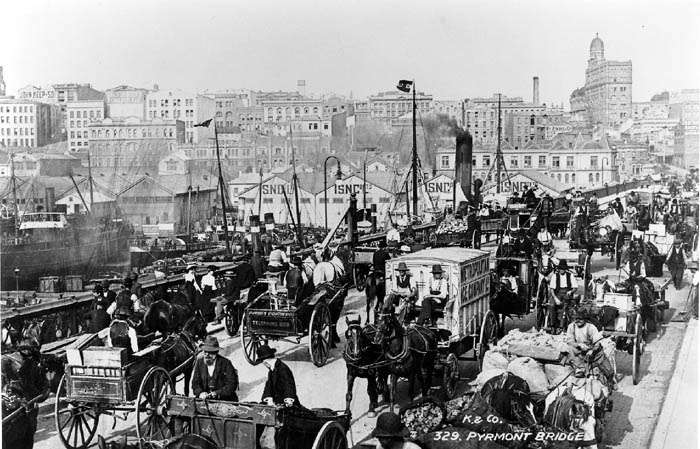

Ad for Winton Motor Carriage in 1898. Picture links to the Stephen Davies article of 2004 that started the epidemic of tongue clucking about short-sighted 1894 city planners.

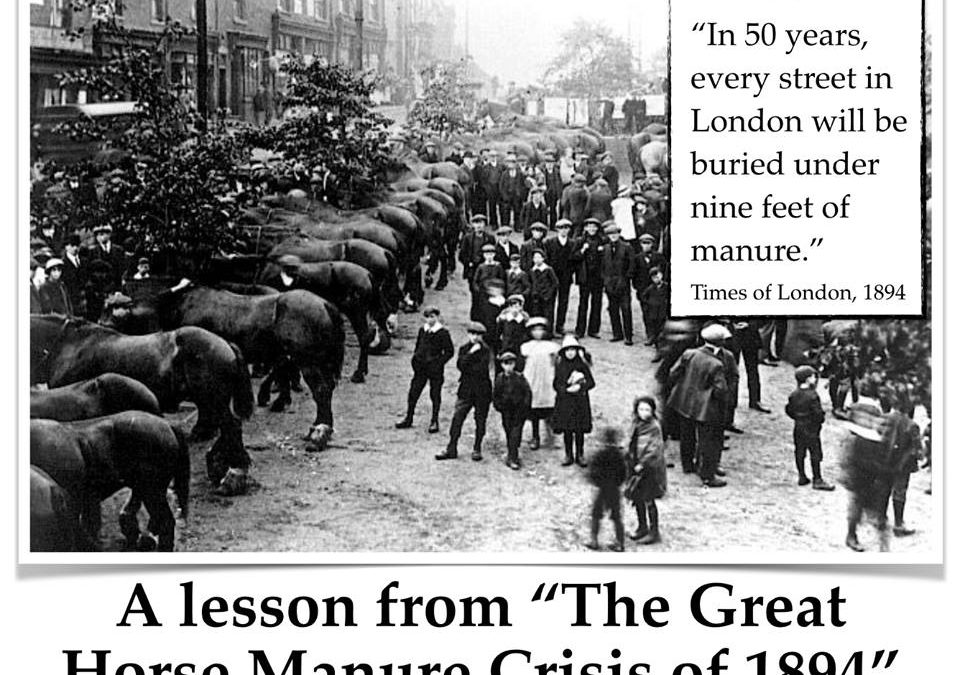

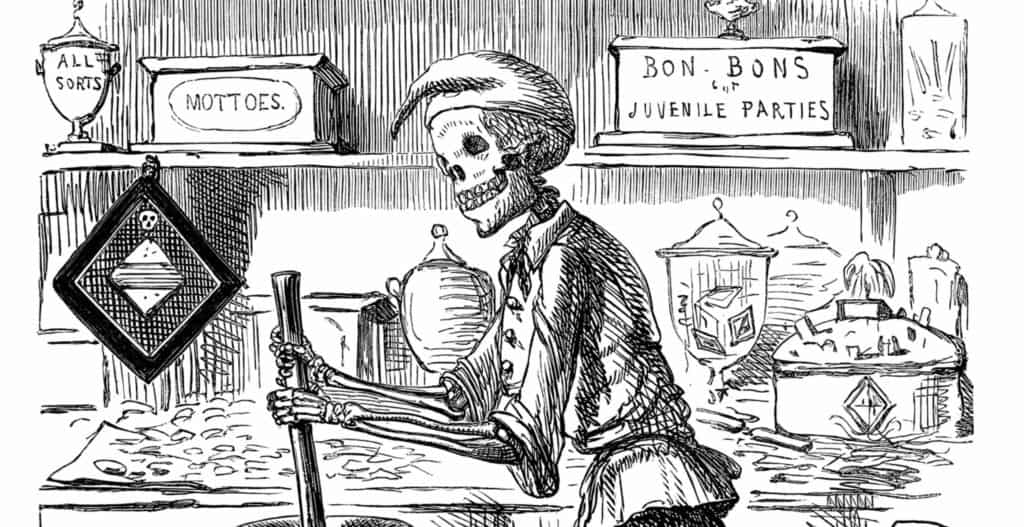

The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894 seems to have originated in 2004, in an article entitled “The Great Horse-Manure Crisis of 1894,” published by the Foundation for Economic Education, written by historian Stephen Davies. He asserted that the accumulation of horse manure was seen as such a grave public problem in the nineteenth century that general panic and despair ensued because the problem seemed hopeless. He asserts that publication of an article in the London Times in 1894 said, “in 50 years every street in London would be buried under nine feet of manure.” He also cites the frustrated, early cancellation of the first international urban planning meeting, in New York in 1898, because no one could solve the problem. He couples that with well-known, widely available, contemporary estimates of the number of horses in various large cities, and the pollution and despair they caused, to posit a desperate crisis. Did it happen? Was mankind in a panic about its cities being immenintly dung bound? Oh dear.

It must be true. A recent (2020) Google search yielded over 120,000 hits on "Crisis of 1894." Mr. Davies has become an oft-cited expert on the dangers of extrapolating today's discomforts into the unavoidable calamities of tomorrow. He is, of course right that extrapolating the trends of the moment into the deep future is nonsense. Still, using a false premise to reach a true conclusion adds nothing to the credibility of either the logician or the conclusion.

The image links to a PBS "documentary" that imagines politicians and planners of the 19th century being puzzled by the accumulating horse manure. If there is evidence of contemporary panic, it goes uncited.

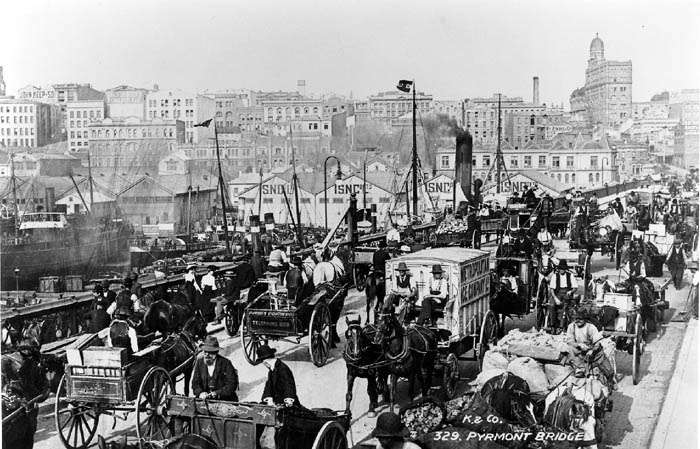

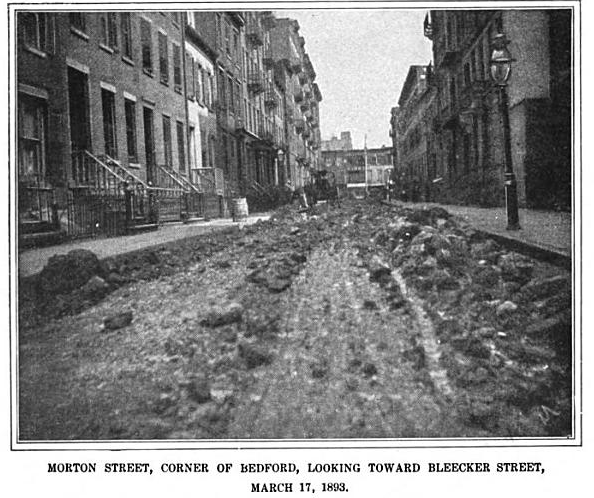

The story has spread around the Internet like a prairie fire across north Texas. Davies’ description of the London Times article, without attribution, is often enclosed in quotes, as if The Times actually printed those words. Davies offered no specific citation, beyond the year, 1894, and did not name the writer of the supposed Times article. Likewise, he offered no substantiation for the supposed urban planning meeting. Thousands of articles, master’s theses, jokes, and morality tales now litter the Internet to a depth rivaling the supposedly anticipated horse manure. Most of these simply recycle the same wording, some adding synonyms and adjectives, as if sourced from Genesis. So far, no references to the “panic” prior to the 2004 Davies article have turned up. Contemporary accounts certainly detail the problems with horse power, and they were numerous, unpleasant and multiplying, but extrapolating them to a sense of futility and panic is a connecting-of-dots almost as egregious as the tellers of this tale attribute to their nineteenth century ancestors.

The image links to one of the plethora of modern problem solvers captivated by Mr. Davies' gentle fiction. Who knew linear thinking needed so much debunking?

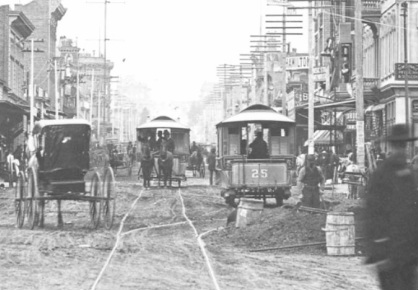

In fact, the internal combustion engine was already hard at work in the world by 1894, along with the mobile steam engine, and by the turn of the century they were widely predicted to take over much of the world’s transportation. The nineteenth century equivalent of modern futurists were predicting automobiles as the soon-to-be conveyance of personal choice and “traction engines” the future of freighting. There was the small problem of fuel, since the petroleum boom had not yet started, but alcohol, biofuel, and electricity were seen as possible alternatives in that tender age.

The widespread panic is alleged to have crossed the Atlantic Ocean from London. Could it have been the reason Gladstone stepped down that year as Prime Minister?

The Davies story has gained regnant attention because it neatly gives shove to the handwringing fatalists of our own age, who despair at the putatively certain continuation of all bad trends. Given two data points and a straight edge, everyone is a prophet, and there is no end to the doom we can foresee by assuming bad things today will continue tomorrow. It is a neat illustration of the need to look beyond the continuation of current unsustainable trends, and has been cited to that end by seemingly everyone trying to make that point in recent decades.

Perhaps the London Times actually published such a story in 1894. Perhaps a meeting of urban planners really did adjourn in despair of shoveling all that manure. Newspapers do publish prattle intended as sensation, and bureaucrats are easily discouraged. We are not the first to question the story. So far no author of the 1894 article has been identified, nor has the article itself been published in facsimile, nor have the minutes of the 1898 meeting been produced, even though a planning meeting at that time is referenced in contemporary accounts and apparently did occur. Most tellingly, no contemporary indication of panic and despair (on that subject) have been found.

It is a neat story. It perfectly illustrates a truth we instinctively understand. There is no reason to believe it actually happened, and, if such a story were needed to invalidate linear extrapolation as a means to the future, we would have to believe forecasting the future is a pretty easy thing. I didn’t see that one coming.

There actually was a panic going on in 1894, left over from 1893. Broadway picked up on it in 1896, in a melodramatic way, making it far less than it actually was, although infinitely more entertaining.

Who in the world cares about horse manure?

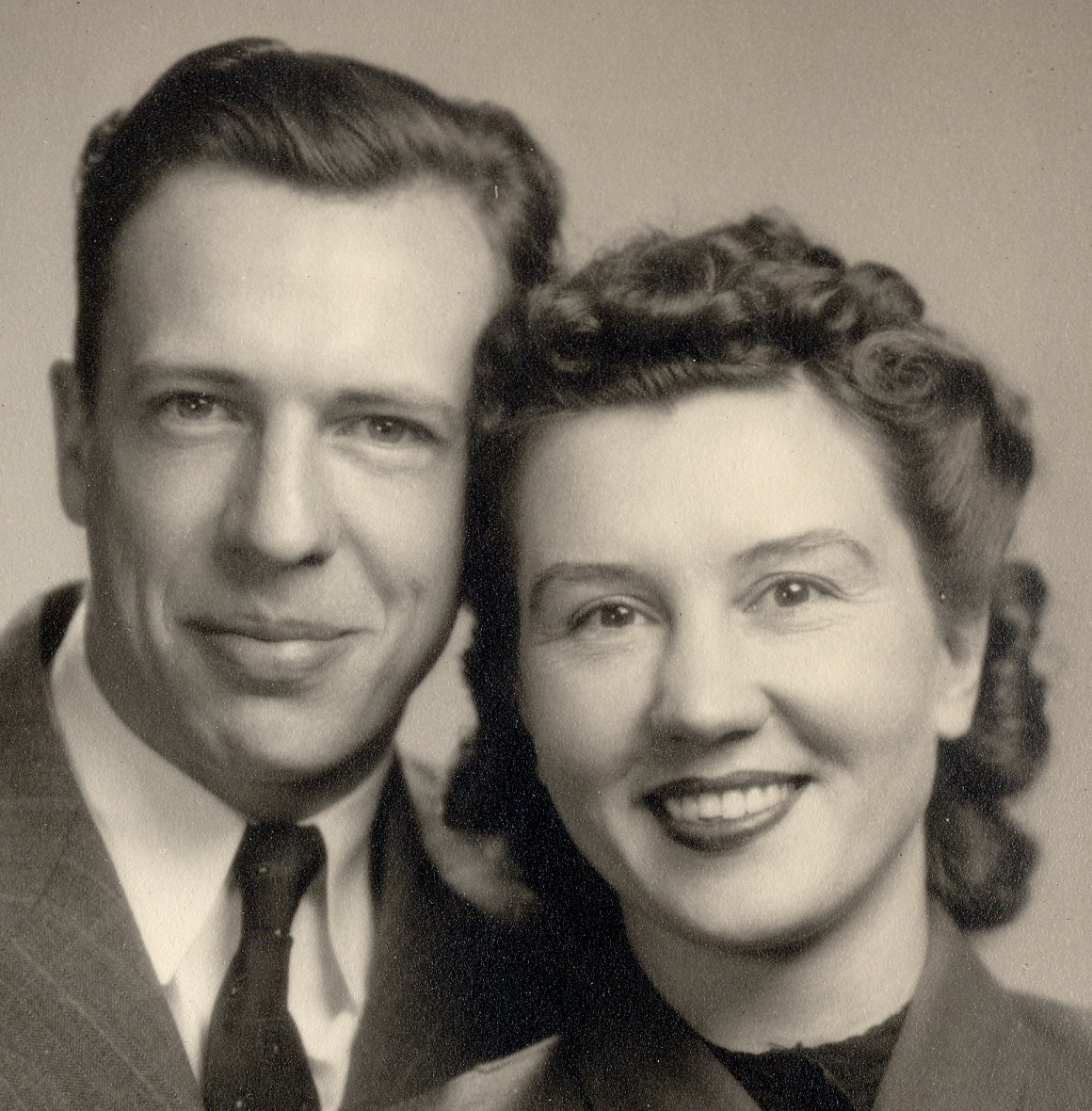

I met dad and mom when they were 27 and 26. This is how they looked then, and always. They were in the first years of a long adventure that began with World War II, and ended in the next millennium. They had lives before we met them, and even before they met each other, and their life with us was a continuation of their separate paths. But to us, their children, their lives were the normal order of the universe. I was far into adulthood before I realized how rare was their gift to us. There was never a day when I doubted their love and dedication.

Dad's ability to guess the shape of the universe from a minimum of data was his most important trait. It was reflected in his rapport with machinery, and apparently inherited. His own father was a oil driller from the days when holes were literally punched into the ground, and my father spoke in awed tones of his ability to, "grab the cable as it dropped the bit, and know how deep the hole was, the composition of the soil, and whether the hole was straight or slanted."

My own father was a machine healer, laying on hands. He knew how things worked, whether mechanical, electronic or theoretical. He could also, in later life, look out his front window in rural New Mexico, watch the traffic go by, and know what was going on in the neighborhood. "They've struck oil on the ___ place, but the well caved in when they got the mud wrong, so now they're trying to shore it up with casing." Or. "They've dropped the water table too low, and they can't irrigate anymore. They're selling out and moving to town." Every observation went into a working theory and all the pieces fit together. He wasn't always right, but he always converged toward the truth.

He suffered all his life from emotions beyond expression. He seems never to have had the necessary signals from his parents to be sure how they felt about him. "I thought there was something wrong with me," he confided, a few weeks before he died. His little brother, Eldy, was two years younger than him, and they were exceptionally close. Sometimes he talked about their years of living together when he was attending college, how they fixed up an old car together. During the war my dad was ineligible for the draft because of a football kneee. His older brother was at Pearl Harbor and made a career in the Marines. His little sister was a WAC. His little brother was a pilot, shot down over Germany in the war's closing weeks. Dad seldom spoke of any of this, but nurtured self-doubts and grief the rest of his life. Eldy was ever near the top of his thoughts. In his last year I was helping him with some paper work and needed the password to his computer. "Eldy," he told me.

Mother was reared by parents from rural Missouri. Their nineteenth century ancestors were products of the southern rural culture, and my mother was very close to them all their lives. Nevertheless, she somehow dodged their prejudices. The first, and most frequently voiced lesson Mother taught her children was the simple truth, "People are people, and you can never tell what someone is by looking at them or where they're from. In all groups there are good people and bad people, smart people and not-so-smart people, talented and untalented, hardworking and lazy. You have to get to know the person, not where they come from." How she acquired that knowledge is mysterious, because it didn't come from her parents. It was indicative of her inner self assurance. She was her own person, always, and she had the ability to make people accept her for who she was, not for who she was with. That legacy was her most important contribution to her children's happiness. "Don't worry about what someone thinks of you if you're doing the right thing. Those that matter will think well of you and the others don't matter." Heady stuff for a two year old to hear.

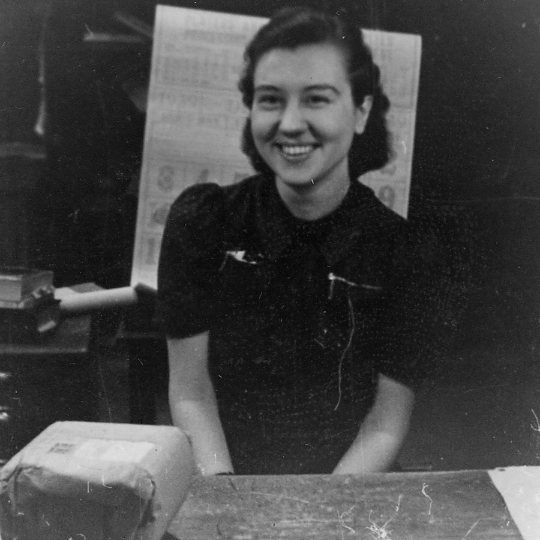

Dad was born in Meeker, Colorado, and spent his childhood following his father around the oil fields of Colorado, Montana and Wyoming. He graduated from the University of Montana and got a job with Standard Oil in Rawlins, Wyoming. That's where he met our mother when she was working in the post office. At her memorial service Dad remembered, "I was impressed at how kind she was. The migrant workers bought money orders to send back to their families, and she counseled them on how much they could afford to send and how much they needed to live on. I liked that and decided to see if I could get her. And I did. I got her."

We were always told mother was born in Cherry Box, Missouri, which sounded like a real place to youngsters. In fact she was born in a farmhouse near Cherry Box, which was little more than a post office. Her parents had trouble making a go of farming, and pulled up stakes in the mid 1920s for Nebraska. They moved around following work, and she graduated High School in Wyoming. She inherited the forceful personality of her Stasey ancestors, and their gregarious leadership nature. All her life, wherever she lived, in whatever circumstances, people knew her and valued her friendship. In her last years she would wheel through the halls of her assisted living home, stroke impaired and unable to walk or speak, to be greeted by everyone she saw, waving her one good arm, smiling and doing her best to offer a greeting. Indomitable. Unquenchable. When she passed away my first thought was, "She must have been ready to go, because if she wasn't, she wouldn't have." Everyone in the home, her latest batch of friends, attended her memorial.

Shortly after they were married, our parents moved to Richmond, California, when Dad got a transfer to the Richmond Standard Oil refinery. They were there during the war, Dad being deemed more valuable making gasoline than soldiering. After the war they followed the Stasey grandparents to rural Missouri. The motivation for leaving a well-paid job in his chosen profession, chemistry, for the uncertainties of farming, is ever a mystery. The standard answer to that question when it came from outsiders was Dad's health. He suffered respiratory problems all his life, from allergies and the after-effects of the 1918 flu. Maybe. But it may also have been Dad's lifelong aspiration of becoming a writer. Or, his desire to escape…from his brother's death, from questions about his war experience, from the mid-thirties blues, or from the daily routine of living. Anyway, he wasn't a farmer, and when his dad passed away, he threw in the plow and went back to professional life with Standard Oil. Those years on the farm are my go-to childhood memories, amazing formative years. I'm forever indebted to my parents for that experience.

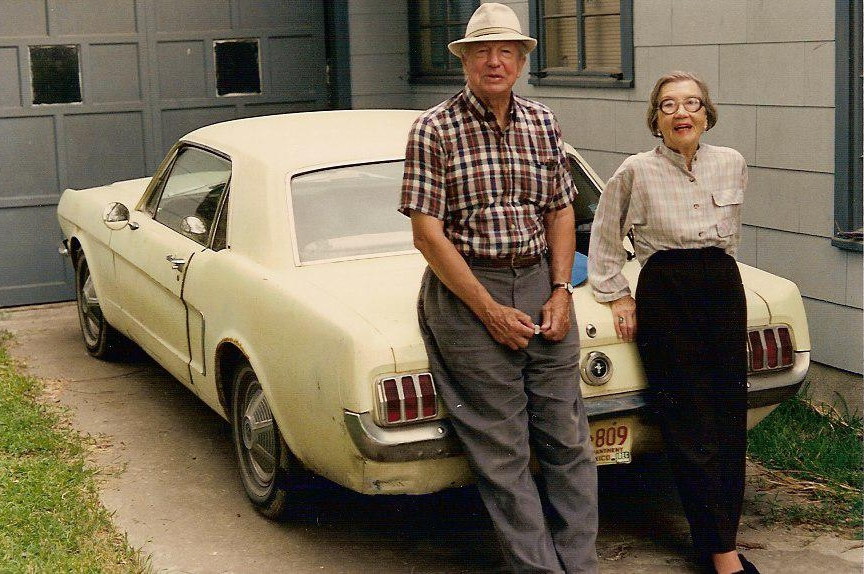

From Missouri the family went to Rangely, Colorado, where Dad's parents had retired and where his mother needed help, to Carlsbad, New Mexico, where he worked in the potash industry, to Hobbs, New Mexico, more potash refining, and then into a series of jobs in his later career that took him finally to Odessa, Texas. While in Carlsbad, during the 50s and 60s, they were active in church, Little Theater, Toastmaster/Toastmisstress, and other civic activities. After retirement they moved to a small acreage near Loving, New Mexico where they lived on a rocky outcropping of the former beachfront of the ancient Permian Sea, now desert from horizon to horizon. It had the advantage of low vegetation which suited what his sister Anne referred to as his, "snout." That is, his allergies.

In retirement, they again lived a rural life, but with the advantages of nearby civilization. Dad continued proving he was a better tractor mechanic than farmer, and pursued a leisurely retirement until it became physically impossible for them to continue. They sold up, moved to Austin, Texas, and lived in assisted living homes until they passed away in 2005, within five months of each other. Even there Dad had his collection of scrap metal and spare parts at hand, a tool box, and some heavily customized potty chairs and power scooters. A few days before he died he was modifying his scooter to improve its performance and get his oxygen bottle attached. I haven't visited their graves in Carlsbad in a few years, but I wouldn't be surprised to find some scrap metal stacked nearby, and perhaps an incoming power line. I'm sure he knows exactly what's going on around him, and I'm sure our mother has made friends with everyone.

.jpg)